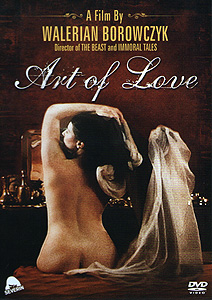

The Art of Love/Ars Amandi (1983) **

The Art of Love/Ars Amandi (1983) **

Hey, everybody! It’s time for another installment of “Art or Smut?” Our celebrity guest host this episode is Walerian Borowczyk, probably best known these days as the director of The Beast (unless you’re a regular B-Fest attendee, in which case I’m betting you know him more for his 1968 short film, Gavotte). Although hailing originally from Poland, Borowczyk spent most of his working life in France. He initially concentrated on animated shorts, most of them with a pronounced left-political subtext— although we’re talking here about leftism in its Western European sense, which is something rather different from the secondhand Stalinism of his homeland. In any case, by the late 1960’s, Borowczyk had expanded into both live action and feature length, and contemporaneously with the shift in format came a shift in subject matter. Particularly once the 70’s were properly underway, Borowczyk’s work focused more and more obsessively on eroticism, so that he eventually developed a reputation as one of the continent’s foremost highbrow pornographers. In other words, it would have been just like him to make a movie out of a 1st-century Roman seduction manual— especially if the manual in question might have played a role in its author’s troubles with the authorities.

At this point, I suppose I have a second introduction to make, considering how little attention schools these days pay to Classical Antiquity. Publius Ovidius Naso— known to English-speakers with no patience for long-ass Roman names as Ovid— was a poet active around what we now think of as the changeover from BC to AD. Most of his career was spent in Rome itself, but he was exiled by order of Caesar Augustus in AD 8, and spent his final decade in the Black Sea coastal city of Tomis. The circumstances are puzzling to say the least. To begin with, banishment was normally a matter for either the regular judicial system or the Senate, but Ovid’s was one of several exiles and executions imposed at roughly the same time by the emperor on his own personal authority. Two of Augustus’s own grandchildren also got the boot, and one of his grandsons-in-law was put to death. It was rather a grab-bag of offenses the aforementioned imperial relatives committed: Julia the Younger (the emperor’s eldest granddaughter) was exiled for having an affair with a senator; her husband, Lucius Aemilius Paullus, was killed for his part in a conspiracy to assassinate Augustus; and nobody really knows why Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa Postumus was packed off to the island of Planasia— maybe he was in on the conspiracy, too. As for Ovid, the timing of his involuntary permanent vacation has led some scholars to suggest that perhaps he was aware of the plot against the emperor, and was later found to have kept his mouth shut about it. The poet himself implied that some of his writings were to blame, however, and the innocuous character of most of them suggests that the likeliest culprit, if that’s true, was a three-volume book of didactic verse called The Art of Love. The supposition among those who favor the Art of Love hypothesis has it that the book, despite having been written with less-than-serious intent, ran afoul of Augustus’s laws aimed at encouraging strictly monogamous marriage. The Art of Love, you see, presented itself not merely as a how-to book on seduction; to a significant extent, it was a how-to book on the seduction of married women. It makes some sense, then, that it would piss off a ruler who had such a hard-on for marital exclusivity that his new laws not only criminalized adultery, but expressly permitted the vigilante killing of cheaters and their partners under certain circumstances. Of course, if that’s really how it went down, then one has to ask why Augustus waited some seven years after The Art of Love was published to move against its author, so maybe the book was but a pretext for Ovid’s expulsion, or had no connection to it at all except in the poet’s own mind. Regardless, Borowczyk makes it clear that he’s going to be assuming the truth of that story when he begins his own Art of Love with a caption reading, “Rome, 8 AD.”

I gather that Borowczyk is also playing a bit fast and loose with Ovid’s means of earning a living, because he has the poet (Massimo Girotto, from The Giants of Thessaly and Baron Blood) leading what looks very much like a modern-style college class in which he stands up behind a lectern and more or less recites verbatim the text of The Art of Love. Granted that the ancients had somewhat different educational norms than we do today, and granted also that philosophy was considered a profession in Roman times, it nevertheless strikes me as improbable that one could sign up in those days for a lecture series on how to score with any and every woman one wished. Be that as it may, that’s exactly the context in which we’ll see Ovid more often than not— even in the scene meant to represent his banishment, when a squad of soldiers storms into his lecture hall to arrest him before he can finish corrupting the young women to whom he had lately extended the benefit of his instruction. We’ll hear Ovid more often than we see him, though, for each of his lectures sets the tone for the ensuing scene in one way or another, and he generally prattles on for a while in voiceover even after the camera has cut away to what I’d call the real action if it seemed like there was any concrete point to it all.

The closest available facsimile of a plot concerns the affairs— in every sense of that word— of several well-to-do ladies. The one we get to know best (and the one who is revealed as the doppelganger of the true protagonist when The Art of Love turns out to be All Just a Dream for no obvious reason at the end) is called Claudia (Marina Pierro, of Immoral Women and The Living Dead Girl). She is the wife of Marcarius Calumbarus Urbano (Michele Placido, from Beach House and Tiger in Lipstick), an officer in one of the legions headquartered in Gaul. Naturally, that means Marcarius spends a lot of time outside of Rome, leaving his wife in the care of his widowed mother, Clio (Laura Betti, of A Hatchet for the Honeymoon and Twitch of the Death Nerve), and an African slave named Sepora (Mireille Pame). The chaperone Marcarius trusts most, however, is a talking parrot, who will presumably pick up and repeat whatever pillow talk he overhears between Claudia and any man she should welcome into her bed while her husband is away. That bird is a real pain in Claudia’s ass, too, because her lover is far from hypothetical. She’s been seeing a young man by the name of Cornelius (Philippe Taccini), who not surprisingly is one of Ovid’s avid students. This sideline romance is complicated yet further by the fact that Sepora is in love with Cornelius, too, but the adulteress needn’t worry overmuch about that for the present; among Ovid’s teachings is the principle that no competent seducer should bother with a mere slave until after her mistress is securely in the bag.

Meanwhile, Marcarius’s commander, Laurentius (Philippe LeMaire, from Spirits of the Dead and Obscene Mirror), has a fidelity problem of his own. His wife, Modestina (Milena Vukotic, of Blood for Dracula and The House of the Yellow Carpet), is cheating on him with Rufus (Salo: The 120 Days of Sodom’s Antonio Orlando), another of Ovid’s pupils and a member of the household of the Consul Nereus’s young and beautiful widow (Simonetta Stefanelli, from Homo Eroticus and Intimate Relations). Modestina has been feeling neglected ever since the general got it into his head to seize the imperial throne— which, to be fair, is an undertaking that would require a great deal of complex and time-consuming preparation in order to do it right. It also surely doesn’t improve Laurentius’s appeal when he does things like to fly off the handle over nothing, slap Modestina around, and lock her in the dog kennel for the afternoon. You just know Laurentius is the kind of guy who’d take full advantage of those vigilante murder clauses in the Augustan anti-adultery laws, too, so Modestina had better hope Ovid has a lecture on techniques for avoiding discovery scheduled soon.

To the extent that we can speak of a turning point in a story that just barely exists in the first place, the crux of The Art of Love is the party that Claudia throws at her villa to welcome Marcarius and his fellow legionnaires home from their latest campaign. Because there’s just no excuse for a European sex movie set in ancient Rome not to include a big damn orgy sequence, the gathering would be doomed to succumb to a tsunami of hormones even without all the overlapping infidelities driving this one. Claudia spends the evening splitting her time between Marcarius and Cornelius, even contriving to sit between the two men at the dinner table. (Note that the latter piece of her scheme would do her little good had Borowczyk remembered that upper-class Romans ate reclining on couches rather than sitting in chairs.) Ovid, too, makes a move on Claudia during the party, although he gets nothing but a brutal snubbing for his efforts. The widow Nereus brings Rufus along, giving Modestina ample opportunity to indulge her ardor while Laurentius drinks himself stupid and coerces a blowjob from Sepora. And speaking of people drinking themselves stupid, even Clio gets in on the action when a handsome youth called Flavius (Pier Francesco Aiello) passes out in the garden, giving her an excuse to have him moved to her own bedroom. Unfortunately, Laurentius does not pass out, and The Art of Love starts to turn ugly when he just barely fails to walk in on Modestina and Rufus.

The Art of Love falls into much the same frustrating zone as Just Jaeckin’s The Story of O. Although competently made, visually pleasing, graced with a potentially strong premise, and certainly sexy enough, it constantly sabotages itself with an unwarranted sense of its own importance. Sometimes that sort of disconnect between dead-serious treatment and ludicrously undeserving subject matter can be a fine thing, but the trouble here is that Borowczyk never quite leaves the foothills of mere pretentiousness to scale the peaks of full-blown megalomania. To be sure, he does occasionally seem to be thinking about making that climb. For example, there’s a wonderfully delirious sequence at about the halfway point when one of Ovid’s lectures and one of Claudia’s erotic dreams converge on the story of Pasiphae’s seduction of the Cretan Bull (which led, nine months later, to the birth of the Minotaur). Whatever we thought we were watching before gets put on hold, and we are treated to a dramatization of the legend, in which Marina Pierro climbs naked into a decoy cow and gets fucked by a man wearing a giant, bronze-finished bull mask, the copulation itself intercut with footage of cattle mating. The present-day epilogue has a similarly disorienting effect, largely because it attempts to cram an entire other movie’s worth of plot into just two scenes via the impressively inelegant means of making one of the characters spend the whole of the second one reading a newspaper article. Furthermore, the story told in the paper could scarcely be less compatible, tonally speaking, with what we’ve just spent 80-some minutes watching. I think I’d have enjoyed The Art of Love more if it had lost its mind like that more often. As it is, what we have here is a movie that meanders very slowly among tenuously connected set-pieces that don’t add up to much, and are furthermore assembled in an order that tends to obscure what little adding up they manage to accomplish. There’s also the ghost of a rhetorical point visible mainly in Borowczyk’s decision to end the Roman portion with the arrest of Ovid by troops under Marcarius’s command, but the disorganization of the film is such as to leave no clear impression of what it was supposed to be. As an art film, The Art of Love is an impressively mounted failure; as pornography, it will go over best among those who greatly enjoy watching pale-skinned women take baths, or who have a thing for the sexual molestation of statuary.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact