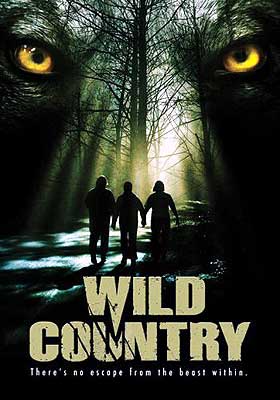

Wild Country (2005) ***

Wild Country (2005) ***

First of all, can I just say how thrilled I am to be writing about something other than fucking Star Wars again? Because holy shit was it a stupid idea to take on the whole Christless prequel trilogy in one go! Wild Country turns out to be the perfect cooldown lap after the Naboo Death March, too. It has no intricate fictional worlds to construct, no aspirations to epic scale or operatic emotional heft, no pretentions of any kind to be more than the simple quickie monster flick that it is. Yet despite that, it rewards close attention with a smartly written script and an unexpected depth of characterization, considering how little time writer/director Craig Strachan invests in back-story.

When teenaged Kelly-Ann (Samantha Shields) got pregnant by her similarly juvenile boyfriend, Lee (Martin Compston, of Strippers vs. Werewolves and Doomsday), it didnít seem like that bad a deal to her in and of itself. I mean, obviously it was a lot of responsibility to take on at her age, but it was something she wanted to do sooner or later anyway, so why not now? Her parents had other ideas, however. Although there was no prospect of getting the pregnancy aborted, neither would they countenance their little girl becoming a mother while she was still in Sixth Form. Lee was told that Kelly-Ann didnít want to see him anymore; Kelly-Ann was led to believe that Lee had run out on her; and the baby was handed straight over to Father Steve (Peter Capaldi, from Lair of the White Worm and World War Z), the familyís priest, to be put up for adoption. At her age, Kelly-Ann had no recourse but to go along with all of the above, but she hasnít forgiven anyone involved for any of it.

A few months later, Kelly-Ann is one of five members of St. Aidanís Youth Club, the youth ministry overseen by Father Steve, to be sent on an overnight camping retreat in the middle of sheep-shagging nowhere. So is Lee. Thatís a bit awkward, naturally, but it does give the two kids a chance to compare notes, and to uncover the duplicity of the girlís parents. The other three campers are a pair of brothers called David and Mark (played by real-life brothers Kevin and Jamie Quinn) and a girl by the name of Louise (Nicola Muldoon), the latter apparently a friend of Kelly-Annís. The model for the retreat is rather surprising, in that Father Steve will not be spending the night with the five teens. Rather, heíll be lodging at a bed and breakfast run by an amorous young woman named Missy (Karen Fraser), which will also serve as his rendezvous point with the campers the following morning. So basically, Father Steve is blowing off his responsibility for keeping the kids out of trouble in order to get into some of his own. Thatís all some hours into the future, though. In the meantime, as the delinquent priest drives his charges out into the countryside, he regales them with the tale of Sawney Bean, patriarch of a clan of cannibal highwaymen who roamed the area where theyíll be camping several centuries before. What would a night in the woods be without a good spook story to set the mood, right?

The hikers get their first little taste of backwoods horror late that afternoon, when they encounter a shepherd (Alan McHugh) plenty creepy enough to be a descendant of Sawney Bean. They meet him again after dark, too, when Kelly-Ann finds him attempting to spy on her while she pisses in the patch of woods beside the campsite. The boys drive the pervert off in short order, but it quickly becomes apparent that Peeping Angus is the least of their worries. No sooner has he emerged from the other side of the copse where heíd been hiding than the shepherd is set upon by some ferocious beast; when we get a decent look at it later, it turns out to be something like an Andrewsarchus.

Some time after the Pervo-Shepherd incident, after Mark has gone to sleep, and after David and Louise have withdrawn to their tent to do things that Father Steve would pretend not to approve of, Kelly-Ann hears a distant sound that she could swear is a baby crying. Following the sound leads her and Lee to a crumbling Medieval ruinó and yup, thatís a baby alright. Just barely have the two teens begun puzzling over what an unattended infant could be doing out here than one of them quite literally stumbles upon the shredded and partially eaten corpse of Pervo-Shepherd, which seems to settle the question. Kelly-Ann jumps to the plausible conclusion that whatever had the shepherd for dinner is saving the baby for a midnight snack, and she brings him along when she and Lee skedaddle back toward the campsite. In doing so, however, they win the ire of the Andrewsarchus thing. It follows them back to their sleeping and/or screwing friends, and makes sure that the only campers who have a restful night are the two whom it kills early on.

The three survivors take a counterintuitive gamble in the aftermath. They loop around and head back to the castle where they already know the monster lairs, on the theory that at least they wonít be out in the open anymore, wondering where and when the next attack is going to come. Besides, the castle is a defensible locationó I mean, thatís what castles are designed foró and the cramped quarters within its walls will obviate the creatureís advantages in speed and night vision. Hell, there might even be something in the ruins that the kids could use to set a trap for their antagonist. Sure enough, the daring bet pays off so well that Kelly-Ann and company are actually able to kill the Andrewsarchus thing shortly after sunrise. Unfortunately, it turns out the creature has a mateó a bigger, stronger, faster mateó which is none too happy about seeing the pair-bond of its life slaughtered before its eyes.

The second monsterís emotional reaction raises an interesting point. Doesnít desire for vengeance on behalf of a slain mate seem a little anthropomorphic to you? For that matter, doesnít it also seem a little outside the realm of expected animal behavior for the first Andrewsarchus thing to have taken such determined exception to the theft of so small an amount of food as that baby would represent? Look at how the creature hunted the teenagers through the night, too. Markís death was just a matter of speed and brute force, I grant you, but the way that thing got Louise took strategy. It took exploitation of terrain, anticipation of the preyís behavior, and a pretty keen awareness of human physical potential. These fuckers are smart, is what Iím saying, and smart in disconcertingly humanlike ways. So how certain are we, really, that theyíre nothing but animals? And if theyíre more than animals, maybe we should take another look at Father Steveís story about Sawney Bean and his clan. What if those folks were more than humanó like maybe a steady diet of long pig turned them into werewolves or wendigos or whatever? And didnít the priest say something about the cannibalsí descendants still dwelling in these parts? Ohó and one last question: if the kids from St. Aidanís Youth Club really are facing some kind of lycanthrope here, should we maybe think again about that baby Kelly-Annís been carrying around ever since she found him in the creaturesí lair? Understandable fantasies of surrogate motherhood notwithstanding, perhaps Kelly-Ann ought to consider keeping her tits away from the childís mouthÖ

Itís a neat idea, but the werewolf angle is the one thing that Wild Country gets really wrong. Weíre supposed to be surprised, you see, when the monsters turn out to be semi- or ex-humans, but weíve already been cued to expect just that from about the earliest moment when setting up expectations is even theoretically possible. We know just from glancing at the video box that Wild Country is a monster movie of some kind, so when Father Steve opens up his yap about Sawney Bean, any remotely genre-savvy viewer will make at once the connection between the Bean clan and whatever the monster is supposed to be. Throw in a creature design that reads as even vaguely canine, and *boom*ó everyone knows itís a werewolf, no matter how many obfuscating tweaks to the usual lore you include. Donít build the final scene around somebody turning into a beast and act like itís some shocking twist.

That said, some of those obfuscating lore tweaks are really quite interesting, especially since there isnít any character whose job it is to explain such things. The audience is left as deeply in the dark as the St. Aidanís Youth Club, which enhances the suspense once it becomes apparent that Wild Countryís werewolves are not of the stock variety. Most notably, lycanthropy here isnít apparently tied to the lunar cycle, and it certainly isnít tied to the rising and setting of the sun. Itís also possible that the transformation from human to animal is a one-and-done thing, like a more extreme version of how it works in Wolf. Finally, the sheer strangeness of the creature design slips in through the back door a suggestion that maybe werewolf was never the right name for things, and that people in olden times were just making do with the best nomenclatural analogy they could think of.

Wild Countryís most offbeat point, and the thing I like best about it, has little to do with lycanthropy, however. Rather, itís the filmís emotional engine, which is Kelly-Annís resentment and depression over having her baby snatched away from her by her parents and Father Steve. Her grudge of thwarted maternity lurks in the background of every decision she makes, and although itís tempting to say that the consequences are disastrous for her in the end, itís equally tempting to say that she ultimately gets exactly what she wanted. Strachan is clever enough, too, to spot the precise moment when it becomes necessary to move Kelly-Annís post-partum neuroses from subtext to text, and to make that move in the most wrenching way. If nothing else, itís perfect that Father Steve, of all people, is the one to connect the dots when the girl barges into Missyís B&B bearing both somebody elseís infant and a seemingly impossible story. It took me very much by surprise how well Samantha Shields and the other young actors making up the core cast sell this stuff, too. Watch a lot of teen-centric horror flicks, and you quickly learn to adjust your standards of acceptable acting downward until you reach the Mohorovicic Discontinuity, but these kids really have something. Peter Capaldi is impressive too, for what little screen time he gets, hitting just the right note of venal skuzz. Iím sure I canít be the only collector of Creeps Played by Past, Present, or Future Doctor Whos, so maybe Capaldiís performance will serve as an incentive for some people to give Wild Country a shot even if nothing else Iíve said so far offers sufficient enticement.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact