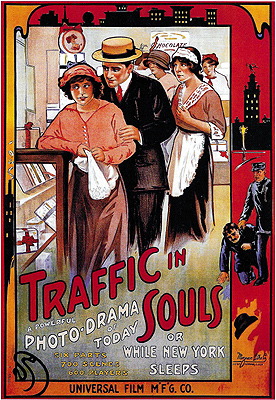

Traffic in Souls/Traffic in Souls, or While New York Sleeps (1913) **½

Traffic in Souls/Traffic in Souls, or While New York Sleeps (1913) **½

Sex sells. It always has, and everyone knows it. But how do you capitalize on that in a medium that has been given the shortest of legal leashes (cinema was deemed unworthy of First Amendment protection until 1952 in the United States, to say nothing of censorship regimes abroad), within a culture that treats the very word as taboo? It took a lot of ingenuity to resolve that conundrum, and the solution initially arrived at in this country was such that it takes a practiced eye to recognize the earliest generation of American sexploitation movies for what they are. The secret, it turned out, was to make the audience do all the heavy lifting, to seed their heads with salacious thoughts while keeping the screen itself unsullied by anything that even the bluest nose could sniff out as objectionable. Obviously that was quite a challenge. It took a con artist’s instinct for emotional manipulation, a magician’s mastery of sensory misdirection, and a lawyerly gift for lying by telling the technical truth. It also took a convincing pose of scolding moralism, to get the busybodies thinking you were really on their side. Naturally, the technique was refined as time passed, while the hucksters of exploitation tested the tolerances of censors and audiences alike, but the film that first showed the industry how it was done was George Loane Tucker’s Traffic in Souls.

That’s “traffic” as in sex trafficking, at least as hot a topic 100 years ago as it is today. The early 20th century’s mania over “white slavery” (to use the terminology of the age) brought together an extraordinary confederation of strange bedfellows, uniting suffragettes and patriarchal reactionaries, labor activists and immigrant-bashers, traditionalists and utopian social reformers. Each party had its own preferred framing for the issue, of course (all of them tending to efface the distinction between sex trafficking and prostitution in general), but if you put them all together, the resulting narrative forms a virtual Rosetta Stone of the era’s social anxieties: girls from the countryside, drawn by the twin lures of economic independence and a broader menu of lifestyle options, were leaving home for the big cities, where foreign-born criminals were tricking or forcing them into de facto indentured servitude as prostitutes, and laundering their ill-gotten gains through renegade banks with the collusion of corrupt police and politicians. In 1910, the concerted public pressure moved Congress to pass the Mann Act, which forbade the transnational or interstate transport of “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” (It’s still on the books today, although it’s been modified significantly since then. Among the changes, the current version is gender-neutral, and seeks to control child pornography as well as sex trafficking in the ordinary sense.) But passage of the law by itself did nothing to diminish the prominence of white slavery in the national conversation, and that brings me back to our real topic here.

When Tucker approached Carl Laemmle Sr. with the idea for a movie about sex trafficking, the latter man’s fledgling Universal Studios had never produced a feature-length film. Indeed, the entire concept of “feature length” was relatively new to American cinema, and was somewhat mistrusted by both producers and exhibitors. Would the proles who constituted the main audience for movies really want to sit still in a dark room for more than an hour at a stretch? And even if they did, could theaters still earn a profit with the audience turnover rate (closely related to the volume of ticket sales) cut by as much as two thirds? No one could yet say as a general thing, but again, sex sells. If anything was worth the gamble of bringing Universal into the feature business, an in-depth treatment of a lurid topic that had already held the public’s attention for years was it. Just to be sure, Laemmle also rolled out some inspired carny-style ballyhoo, inflating the reported production cost by a factor of 30, and claiming that Traffic in Souls was based on the official report of some imaginary New York state commission to study the problem of white slavery. The bet paid off handsomely. Universal made so much money that there was no longer the slightest doubt about features becoming a regular part of the company’s business model, and other producers ranging from the biggest of the big studios to the most disreputable minor-league roadshow peddler began studying Traffic in Souls for clues on how to duplicate its success. It would be some years before Universal ascended from what would later be called Poverty Row, and many more years still before the likes of Dwayne Esper and Kroger Babb raised sexploitation to its first plateau of maturity, but both of those seemingly contrary processes begin here.

Filling six reels must have seemed a daunting task to filmmakers accustomed to working with only one or two at a time, so it shouldn’t surprise us that Traffic in Souls labors under the burden of far more story than it really needs. There are two main plot threads which merge at roughly the hour mark, but also what amounts to a complete short subject wedged awkwardly into the middle of the film. Subplot A concerns Mary (Jane Gail, from the 1916 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and the King Baggot version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) and Lorna (Ethel Grandin) Barton, daughters of a somewhat dotty widower (William H. Turner) who is identified from the outset as an inventor, but whose talents will not come into play until the movie is nigh over. The girls both work at Smyrner’s Candy Store, and the elder is dating a policeman named Burke (Matt Moore, of I Bury the Living and Tod Browning’s The Unholy Three). One afternoon at work, Lorna catches the eye of a pimp (William Conaugh) who decides that she’d be the perfect addition to his stable. The pimp and his bosses send “Respectable” Smith (William Burbidge) around to press a fraudulent courtship on her. Girls find Smith charming and completely non-threatening, so the mobsters like to use him as bait when fishing for middle-class ass. In this case, Smith takes Lorna out for dinner and dancing, and drugs her drink when she isn’t looking. As soon as she succumbs, the pimp and one of his men (who’ve been surreptitiously observing the date all along) spirit Lorna away to captivity in his brothel.

Subplot B is all about the secret double life of the Right Honorable William Trubus (Queen of the Jungle’s William Welsh), beloved family patriarch, respected businessman, pillar of the community, and to judge from that “Right Honorable” business, sometime holder of important municipal office. He and his wife (Millie Liston, from Neptune’s Daughter and A Daughter of the Gods) are known throughout New York’s high society as advocates for social reform and moral restoration. Trubus is a crusader against crime and corruption, too, having recently organized the Citizens’ League to put pressure on the city government. So naturally none of you will be surprised to learn that he’s also the kingpin of New York’s prostitution racket. With the help of a man (Howard Crampton, of The Screaming Shadow and The Trail of the Octopus) identified only as “the Go-Between” (although I almost immediately started thinking of him as “Stan Jerkhiser”— this is one of those films that practically beg you to invent your own names for their maddeningly many and inadequately identified characters), Trubus controls what appears to be every whorehouse in the city— the one where Lorna Barton ends up confined most definitely included. Subplot B also contains a sub-subplot in which Trubus’s daughter, Alice (The Lost City’s Irene Wallace), is courted by society dandy Bobby Kopfmann (Arthur Stein), their budding romance obviously foredoomed by whatever bad end is waiting in the wings for the girl’s crooked father.

The two threads come together when that dickhead Smyrner learns about Lorna’s abduction, and fires Mary on the grounds that the scandal clinging to her family will… I don’t know… taint the saintly reputation of his candy or something? Commendably, the filmmakers seem to expect us to react negatively to Mary’s sacking. Anyway, Mrs. Trubus has always liked Mary (I guess the lady buys a lot of candy), so she steps in to get her a new job in her husband’s office. Once there, Mary discovers how the boss really makes his living, and with the help of a bugging device invented by her father, she gets Burke the evidence he needs to dismantle the whole Trubus crime empire.

As for the mid-course mini-movie, it tells the story of another pimp on the Trubus payroll (Arthur Hunter) stocking his house of ill repute with fresh merchandise. One of his victims is a girl from the sticks (Laura Huntley) too naïve to defend herself against sophisticated big-city duplicity. Two others are Swedes fresh off the boat (Flora Nason and Vera Hansey) who fall into the pimp’s clutches after he separates them from their brother (William Powers— I swear, have you ever seen so many fucking Williams in one movie in your life?) by arranging his unjust arrest on a disorderly conduct charge. The vignette comes to a happy ending when Officer Burke singlehandedly busts the whole operation, tipped off by the patently phony “Swedish Employment Office” sign the pimp posts outside his brothel to sucker in the two immigrant girls.

If you’re looking for direct titillation, you won’t find much of it here. There is one bit during Lorna’s captivity in which a madam threatens her with a whip, but it’s scarcely hot stuff by modern standards— not least because even the girl’s underwear covers about as much of her as a deep-sea diving suit. But remember, direct titillation was never the point. Tucker is counting on you to respond, when he says “white slavery,” first by thinking “whores,” then by thinking of all the things whores get paid to do. None of that is in the movie— hell, the mere word “prostitution” isn’t in the movie— but Tucker knows how repression works. With an audience as tightly buttoned up as his, all it takes is one little crack in the seal to make everything come bubbling out. The result, for today’s audiences, is that Traffic in Souls looks like much more earnest a social issues picture than it was ever meant to be. Not that I think its makers were in favor of sex trafficking or anything, but external evidence— the dishonest advertising campaign especially— indicates that Tucker, Laemmle, et al. were exploiting the white slavery issue first and only secondarily raising awareness of it. Besides, 1913 was awfully late to go around raising awareness of something that had been all over the news and a favorite topic of agitprop pamphleteers for at least four years.

Traffic in Souls is an invaluable case study for students of early cinema in general (as opposed to just students of early sleaze), because it shows American filmmakers working at feature length before they really have the hang of it. You can see the inexperience in the movie’s amorphous structure, and in its huge surplus of plot. An immense amount of stuff happens over the course of these 88 minutes, very little of it developed as fully as a modern viewer would want or expect, and with only the vaguest sense of rising action holding it all together. The simple fact that what I’d normally think of as the second act could be popped out whole to stand on its own as a two-reeler says a lot about where Tucker’s head was in 1913.

I also believe I detect a bit of influence on Traffic in Souls from the adventure serials that were beginning to capture the public imagination at about the same time. Note, for example, the two sci-fi gadgets that figure in the exposure of Trubus as the mastermind of the New York sex trade. One of these is the telescript machine that enables Trubus to monitor Mr. Jerkhiser’s bookkeeping in real time. A special pen somehow transmits its strokes to an equally special pad in the kingpin’s office; the incriminating record thus formed is part of what alerts Mary to Trubus’s shady activities. Then of course there’s the aforementioned audio bug, in which a mini-microphone hidden under the boss-man’s desk is linked up by wireless to a wax cylinder recorder in Mary’s. Neither contraption was within the capabilities of 1913 technology in the real world, but comparable equipment could be found among the arsenals of both heroes and villains in the chapterplays. Even more serial-like is the proactive role played by Mary Barton in the final phase of the film. Today it seems a little shocking to see such moxie in the heroine of so ancient a film, but the early silent serials were very much a domain of ass-kicking women. Many chapterplays advertised their action-girl focus right in the title: What Happened to Mary?, The Adventures of Kathlyn, The Exploits of Elaine, The Hazards of Helen, The Perils of Pauline, The Active Life of Dolly of the Dailies. Furthermore, since it was normal in those days for serial stars to perform all but the riskiest of their own stunts, actresses like Pearl White and Helen Gibson often lived only a little less dangerously than the characters they portrayed. To be sure, neither Mary Barton nor Jane Gail is in quite that league. Still, you can’t help noticing that Mary isn’t at all the helpless, cowering creature familiar from Hollywood’s supposed golden age. It makes good sense that Traffic in Souls would borrow from the serials, too. There was their popularity, for one thing, which had to have crossed Carl Laemmle’s mind as he entered this risky new field of film production. But beyond that, serials offered a model for long-form storytelling that might have been more accessible than the multi-reel features coming out of Italy and Germany (which would have been the best place to turn for pointers in those days). Sure enough, if you watch several serial chapters back to back in one sitting (instead of spacing them out at weekly intervals, the way they were meant to be consumed), the result frequently looks a lot like Traffic in Souls: unstructured, overly busy, long on subplots yet short on solid connecting material between them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact