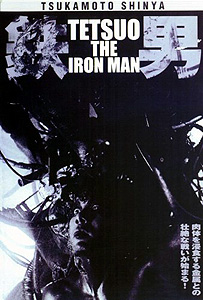

Tetsuo: The Iron Man/Tetsuo (1988/1992) ***

Tetsuo: The Iron Man/Tetsuo (1988/1992) ***

It’s not like I was unacquainted with Japanese filmmaking in 1993, when a rather crappy and perhaps not entirely legal VHS copy of Tetsuo: The Iron Man fell into my hands. I grew up on kaiju and anime, after all, and I sought out as much as my limited means would allow when the late 80’s saw a big influx of bootleg and collector-oriented material in the latter category especially, stuff that never stood a chance of securing a legitimate trans-Pacific distro deal. I’d been exposed thereby to varieties of weirdness that I assumed in my youthful arrogance to have rendered me permanently unflappable in the face of nearly anything: perverted tentacles, steam locomotives that flew through space, alien gods conferring their favor upon chosen heroes via magic walnuts, karate techniques to make your opponent’s head explode next Thursday… even blue-skinned Greek hoplites growing out of the asses of saber-toothed tigers! But even so, Tetsuo was different. Tetsuo was a mindfuck par excellence. I gather that its release was a watershed moment back home as well, because something has to explain the marked turn toward noise, chaos, non-linearity, and self-conscious hyper-surrealism that seemed to take over nearly all of Japanese horror, sci-fi, and fantasy cinema during the 1990’s, and Tetsuo’s timing looks just about right.

A wild-haired young man whose face we won’t see clearly until much later (writer/director Shinya Tsukamoto, who can also be seen acting in Sakuya: Slayer of Demons and Blind Beast vs. Killer Dwarf) walks into an apparently abandoned industrial site, where he descends deep into the bowels of one of the machinery spaces to perform a bizarre bit of surgery on himself. Cutting open the flesh of his right thigh, he takes up some kind of threaded steel rod, and inserts it into the wound as deep as it will go, roughly parallel to his femur. After bandaging himself up (the instantaneous appearance of a horde of maggots suggests that the operation didn’t go quite as well as anticipated), Extreme Body Modification Guy runs out into the city, cackling like a madman— and promptly gets run over by a car when he stops for no obvious reason in the middle of a street. It’ll be some considerable while before we’re able to piece together the significance of all that.

What turns out to be several days later, a salaryman-type (Tomoworo Taguchi, from Tomie and Guinea Pig: Android of Notre Dame) has an odd experience while shaving. He’s just about finished when he notices something protruding from his cheek. It certainly isn’t a hair. In fact, it looks like a few millimeters of metal wire. The salaryman pokes at it experimentally, and something bursts inside his cheek, spraying the mirror with blood. Now I’m pretty sure I’d call in sick if that was the start of my morning, but you know how white-collar Japanese men are. This fool just slaps a big band-aid on his face after presumably extracting the wire tip, and goes on about his day as if nothing were amiss.

There’s no indication that our rather complacent salaryman is actually named Tetsuo, but that’s what I’m going to call him for simplicity’s sake; it’s a fairly common masculine name in Japan, although literally it means “iron man.” My suspicion is that Tsukamoto had both usages in mind when he chose the title for this film. Anyway, while Tetsuo is at work, he gets a phone call from his girlfriend (Kei Fujiwara, of Id and Organ), who makes cryptic reference to a hit-and-run accident. Then, on the way home, he has an encounter so weird and terrifying that not even he can brush it off. Apparently feeling queasy after the long train ride, Tetsuo sits down heavily on a bench in the subway station beside a bespectacled woman (Nobu Kanaoka) who greets his arrival with some alarm. Her attention is quickly drawn away, though, by a clot of somehow organic-looking machinery that seems to have appeared out of nowhere on the floor near her foot. She doesn’t realize this, naturally, but the peculiar gizmo contains a video link to the lair of the masochistic weirdo from the opening scene, and he’s watching with palpable anticipation as she reaches down to prod the device with a pair of tweezers from her handbag. You remember what happened when the old vagrant did much the same thing to the titular space Jell-o in The Blob? Well, that’s essentially how this goes, too, except that when the weirdo’s contraption engulfs the woman’s hand, it turns her into a cyborg zombie under his control. Those of you who are thinking that Tetsuo might have been driving that car in the prologue will have your suspicions redoubled when the weirdo directs the woman to attack Tetsuo. She hounds him what looks like a quarter of the way across town before he manages to destroy her in an auto repair garage that appears to be closed for the day.

That night, Tetsuo has a disturbing dream in which his girlfriend becomes a cyborg succubus, and sodomizes him with a hose-like implement projecting from her crotch. The reality to which he awakens is more disturbing yet, however— Tetsuo has robot cancer. Slowly but surely, bit by bit, his body is transforming into machinery and electronics, and from the looks of things, the process is extremely painful. Not as painful, mind you, as what befalls his girlfriend after she sees what’s happening, and tries to demonstrate that it makes no difference to her affection for him. This is a Japanese movie at least tangentially concerned with robots, so you know there has to be a power drill involved at some point, right? Okay, now which part of Tetsuo’s body do you reckon most likely to be turned into a giant, barely controllable drill as his condition advances?

We might ask at this point exactly how one comes down with robot cancer. Apparently it’s contagious, and Tetsuo picked it up from the guy with the metal rod in his leg after smashing into him with his car. Tetsuo’s girlfriend— who we now learn to have been along with him at the time— might have called what they did hitting and running, but that isn’t entirely accurate. They actually did stop to see if their victim was okay, only when they determined that he wasn’t, Tetsuo hoisted him into the car and drove out to the country to dispose of the evidence, rather than face the consequences of the accident. It would appear that the metal-freak isn’t the only one around here who gets off on some pretty sick shit, because the act of committing such a serious crime got the couple so hot that they had to drop everything and fuck right there at the top of the embankment over which they’d just tossed what they assumed was a dead man. We, of course, know that he wasn’t dead at all— and so did they after the girl looked down into the gully and saw him watching. In any case, the weirdo has some sort of natural biological affinity for machines, clearly connected in one way or another to the hunk of steel that seems to have just spontaneously appeared inside his brain one day, and presumably all the physical contact necessary to get him first into the car, then out of the car, and finally into the gully is what now accounts for Tetsuo’s affliction. The aim of all that manhandling, meanwhile, is what accounts for the vendetta that now motivates the metal-freak. All of the foregoing comes to light a few days after Tetsuo’s girlfriend’s death, when the weirdo drops in at Tetsuo’s apartment to square up accounts at last. And now that we get a good look at Extreme Body-Mod Guy, it appears that his condition isn’t just a disease the way it is in Tetsuo’s case. Whereas Tetsuo is by this point just a huge, hulking, humanoid mass of iron debris, the metal-freak is able to accelerate and reverse the growth of his mechanical parts at will, and has a few metal-specific psionic powers as well. He can control any mechanical or electronic device with the power of his mind, and even induce corrosion in metallic objects by touching them. In other words, he looks like just about the last guy on Earth that somebody with an advanced case of robot cancer would want to have to fight.

Believe it or not, Tetsuo: The Iron Man gets significantly weirder from there. For instance, I haven’t yet raised the subjects of rust symbiosis, television telepathy, the Battle Bum (Renji Ishibashi, from Fruits of Passion and Audition), or Extreme Body-Mod Guy’s supervillain aspirations. In the end, though, the details of the plot, mad as they may be, are only half of what makes Tetsuo the landmark of strangeness that it is. It’s how Shinya Tsukamoto tells this story that truly positions it as the herald of what has come to be called Asian extreme cinema. (Incidentally, have I ever mentioned how much I loathe that designation? I’m not sure what I’d prefer to call stuff like Gozu and 964 Pinocchio instead, but “Asian extreme cinema” sounds like it was dreamed up by the marketing department for an energy drink.) When Tetsuo first made its way to the West, the only point of reference that anyone seemed to be able to find for it was Eraserhead, and that’s not a bad comparison if we’re talking strictly about style and technique. Shinya Tsukamoto and David Lynch both turned budgetary straits into a creative windfall by shooting in black and white, exaggerating the coldness, hardness, and dirtiness of their urban settings until they transformed into inhumane industrial hellscapes. Tetsuo and Eraserhead alike make extensive use of narrative fragmentation and unsettling dream sequences to keep the audience in a state of constant disorientation and uncertainty— and in both films, it can be difficult to locate the boundaries of the protagonists’ nightmares because their realities are equally nightmarish. The big difference is that Lynch used all those devices as the means to an end, whereas Tsukamoto treats them as ends unto themselves. Like many of the movies that appear to take their presentational cues from it, Tetsuo is basically hollow. You leave Eraserhead going, “Wow. That sure was bizarre…” but then you spend the next day or two gnawing at the question of what it meant. In Tetsuo: The Iron Man, “Wow. That sure was bizarre…” is the meaning.

That in and of itself should not be taken to disparage Tetsuo, however. Gaudy trifles have their place, too, and there’s no reason why a gaudy trifle shouldn’t aspire to be uncomfortable and disturbing as well. On that level, Tetsuo: The Iron Man is unquestionably a success. Robot cancer is just a brilliant idea, and one that is probably more effective in this frankly shallow and irrational context than it ever could have been if it were weighed down with a cargo of message and metaphor. The production design is similarly ingenious. Who knew so much potential lay in a few hundred kilograms of junk and scrap metal? And for a lot of the cyborg-centric chase and fight sequences, Tsukamoto made deft use of a strange technique that probably has a proper name, but which I (having no idea what that proper name might be) think of as live-action stop-motion. That is, the film is exposed a frame or two at a time, like in ordinary stop-motion, but instead of inanimate miniature models being moved in tiny increments, the director has his human cast strike a succession of static poses. Regular B-Fest attendees will know at once what I mean when I say that significant stretches of Tetsuo: The Iron Man resemble an ultra-violent, manga-influenced, cyberpunk version of The Wizard of Speed and Time, but I’m not sure how to put it for the benefit of everyone else. All I can say is that the effect is strikingly unnatural, and that I much prefer it to any of the more technologically advanced ways of distorting the apparent passage of time that have plagued action-oriented movies ever since The Matrix.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact