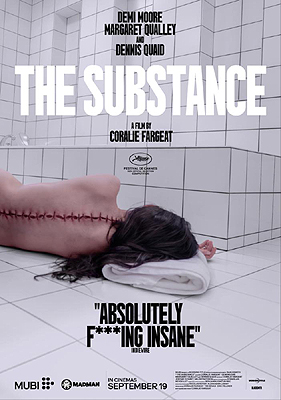

The Substance (2024) ***½

The Substance (2024) ***½

When I first encountered the term “body horror,” back in the late 1980’s, it meant something subtly but importantly different from what it means today. Back then, it had less to do with narrative or thematic content than with the implications of advances in special effects technology. It was the territory beyond mere gore that had been opened up by the concurrent advents of foam latex, air bladders, and cable-controlled animatronics, which made it possible to depict the destruction or transformation of the flesh in process, as opposed to merely juxtaposing the before and after. That usage contained from the beginning the seeds of its own obsolescence, however, because the novelty of those revolutionary techniques would inevitably wear off as they became part of the standard filmmaking tool kit. “Body horror” stuck around, but it narrowed in scope while simultaneously growing fuzzier in meaning, until it became one of those things that are hard to define, but recognizable when you see them. I tend to find terms like that more trouble than they’re worth, so you won’t often find me talking about body horror around here. For The Substance, though? Nothing else but “body horror” does full justice to what this movie is trying to do. The Substance is about bodies on absolutely every level— not just how to wreck them or how to change them, but how we love, hate, fear, and envy them, frequently all at the same time. It’s also about the unreasonable, impossible expectations we place on them, and the lengths to which we’ll go— women especially— in the futile hope of meeting those expectations. Most of all, it’s about how we’re all ultimately stuck with our bodies, and how they will inevitably fail us in the end.

Writer/director Coralie Fargeat is operating in fable mode here, and as is often the case in fables, The Substance’s setting is deliberately nebulous. The place is unmistakably Los Angeles, but the time seems not to be any era that has ever occurred on our Earth. Imagine what the aughts might have been like if America had gotten permanently stuck in the 1980’s, but had premature access to 2020’s technology. For example, Laddie Magazine raunch is the dominant pop-culture sensibility, but half-hour aerobic workout shows remain a significant feature of the daytime television landscape. The undisputed mistress of the latter medium is Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore, from The Seventh Sign and Parasite). An Oscar-winning actress in her youth, with a star on the Hollywood Boulevard Walk of Fame, Sparkle has spent the past two decades or so leading America’s housewives in holding senescence at bay one high-kick, toe-touch, and squat-thrust at a time. So basically Jane Fonda, if VCRs hadn’t stolen televised butt-shaking’s thunder circa 1985. Having just turned 50 (Moore herself is 61), Elizabeth still cuts an impressive figure in a leotard, but the makeup department for her daily late-morning show is finding it increasingly challenging to hide her turkey neck from the camera. Consequently, the boss of the network— an extravagant boor by the name of Harvey (Dennis Quaid, of Jaws 3-D and Inner Space)— reckons it’s time to pull the plug on “Sparkle Your Life with Elizabeth.” Happy fucking birthday, right? I suppose Sparkle should count herself flattered that she still warrants being taken out to lunch to receive her walking papers, but that doesn’t make it hurt any less— especially given Harvey’s perfect frankness about her age being the principal driver of his decision.

Soon after getting sacked, Elizabeth drives down just the right street at just the right time to witness the dismantling of a billboard plugging her newly cancelled show. As the workmen rip her face from the supporting scaffolding, Sparkle becomes so agitated that she loses control of her car, and gets into the kind of accident that only the very lucky are able to walk away from. She’s in the luckiest cohort of all, too, because the doctor who checks her over in the aftermath (Tom Morton) finds no injuries more significant than a few superficial cuts and bruises. Ultimately, however, Elizabeth will be much more heavily impacted by the results of a second, surreptitious examination she gets at the same time from the attending nurse (Robin Greer). He doesn’t say just what he’s been looking for, but as soon as the doctor is out of earshot, he pronounces her a “good candidate,” and slips something into the pocket of her coat. It’s a flash drive marked with the enigmatic legend, “The Substance,” together with a telephone number and a note reading, “This changed my life.” At home, Sparkle plugs the drive into her TV, and watches a pitch no less enigmatic, promising “a younger, more perfect you.” Reasonably concluding that she’s being sold some combination of fad diet and amphetamines, Elizabeth tosses the flash drive and the phone number in the trash.

The thing is, though, that a younger, more perfect her is exactly the thing that Elizabeth desires most right now. It was only a matter of time before she fished that number out of the can and called it. The voice at the other end of the line spouts still more enigmas— “You are the matrix,” “You are the stabilizer,” “Remember: you are one,” and so forth— but enough hints come through to convey that something strange and unique is on offer here. Elizabeth pays up, and a few days later, an electronic key card marked “503” arrives in the mail, accompanied by a street address. The place in question looks at first like a nondescript abandoned building in a neighborhood circling the drain, but down the adjacent alley is a rollup door with an electronic lock. The door in turn gives access to a maze of grimy and almost pitch-dark corridors, but at the end of that is a brightly lit and spotlessly white room lined with numbered drop boxes. Box 503 contains a kit including some alarming hypodermic gizmos, an even more alarming suturing set, an array of unusual medical glassware, a vial of greenish liquid, a package of what looks like baby food, and an instruction booklet that isn’t half as informative as Elizabeth would like. Okay, so she’s supposed to activate once, stabilize daily, and switch every seven days without fail, but what does any of that mean? Guess the only way to find out is to try it…

No sooner does Elizabeth inject the activator fluid than she is laid low by unimaginable full-body pains and an indescribable psychedelic experience. While she lies on the floor of her bathroom in the throes of all that, her back splits open along the midline, and the promised younger, more perfect her (Margaret Qualley, from Death Note and Io) clambers agonizingly out of her body like a cicada undergoing its final molt. Now it all starts coming into focus. Activation creates the new, perfected body by cloning all of the original’s cells. Stabilization means keeping the clone body in good cellular health with daily injections of cerebrospinal fluid drawn from the original. And switching transfers consciousness between bodies via a large-scale blood transfusion. The suture kit is for closing up the gaping wound down the old body’s spine, and the food paste is for nourishing the mentally vacant body while the other one is in active use. There’s an important nuance to this setup which the Substance’s vendors have neglected to mention, however. Consciousness might transfer between bodies with the transfusion of activated blood, but memory remains locked within each individual brain. Elizabeth’s stunning young alter ego— Sue, she calls her— might start off with all the same synapse wiring and whatnot, but from this point forward, she’ll have no recollection of the weeks her psyche spends back in its old corporeal digs. Nor will Elizabeth ever remember any of the experiences she has as Sue. The Substance pitch reel and training materials might emphasize that the two selves are one, but are they really? That’ll be an increasingly fraught question as Elizabeth’s and Sue’s lives diverge over the weeks and months to come.

Shortly after becoming Sue for the first time, Elizabeth has a brilliantly wicked idea. She’s going to answer Harvey’s casting call for girls to host his prospective replacement for “Sparkle Your Life!” Naturally, Sue crushes the audition— after all, what other 20-something can roll up with two whole decades’ worth of experience hosting a weekday morning workout show? Sue can’t actually put that on her resumé, of course, but with her combination of moves and professionalism, who needs a CV? The new show— “Pump It Up with Sue”— is aptly named. Everything about it is more than “Sparkle Your Life.” Faster pace, louder music, more strenuous exercises. Bigger set, brighter lights, quicker cutting, more radical camera angles. More and sexier backup dancers, including a few buff young men in the back row. And most of all, much more skin exposed by the costumes, all the better to display what the Substance has done for the hostess. “Pump It Up” is an implausibly huge hit, so much so that Harvey doesn’t complain a bit when Sue springs on him the inconvenient requirement to double up their taping schedule, because commitments to ailing relatives limit her to working only every other week. “Ailing relatives” like the 50-year-old lady lying mindless and inert in the bathroom back at Elizabeth’s apartment…

It should be apparent at this point that The Substance is riffing a bit on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and it will be natural in that context to interpret Sue as Elizabeth’s bad side. She’ll give us fair enough reason to think of her that way, too, before this story has gone much further. Put yourself in Sue’s position, though. You’re rich, you’re famous, you’re a rising star. You’re young, with a bright and alluring future ahead of you, and you’re beautiful almost beyond description. How eager are you going to be to give up being those things at the end of the week, just in order to resume being old, faded, and washed up? How scrupulous are you likely to be about following the schedule— especially when switching time catches you, for example, about to climb into bed with a really hot guy? How long before you started itching to cheat? I don’t know about you, but I can’t even be trusted to take out my fucking contact lenses every night like I’m supposed to. Be that as it may, Sue starts cheating essentially the moment temptation first arises— and Sue doesn’t pay a single direct price for doing so, either. No, the consequences for Sue’s perfidy fall solely on Elizabeth, who soon finds herself waking up a day late, or several days late, or even a week late. And whenever Sue steals time from Elizabeth by extracting extra doses of her cerebrospinal fluid, it does decidedly unpleasant things to the older woman’s body. It ages her yet further, for starters, but it also leaves parts of her deformed and prone to malfunction, with the extent of the damage more or less proportional to how long Sue overstays her prescribed week of activity. When Elizabeth calls the Substance customer service number to complain, she’s blithely told that any such changes are permanent and irreversible, and that the only way to prevent more of them in the future is to remember that she and her youthful alter ego are one. Of course, Elizabeth isn’t the one who needs to hear that, is she? And so far as Sue is concerned, that whole conversation might as well never have happened, since she’s reposing at the time in the secret alcove that she and Elizabeth built at the back of the bathroom to conceal whichever of them is dormant on any given day. Sue keeps cheating, Elizabeth keeps paying for it, and the relationship between the two personas descends rapidly toward all-out war. Even then, however, things have only begun to go awry for our bifurcated heroine.

Like practically every movie nowadays, The Substance goes on rather too long. And it plows past not one but two perfect endings in order to serve up a third that’s markedly less satisfactory than either of its predecessors. I feel compelled to give some credit even to the weak actual ending, though, simply for having the nerve to go that far astray, with that much conviction. I don’t want to give too much away, but suffice it to say that The Substance has a turn-of-the-90’s Peter Jackson ending, the sheer exuberant excess of which sits awkwardly beside the quieter, if no less gruesome, Cronenbergian tenor of the film up to then. At the same time, though, when was the last time something you saw at a shopping mall multiplex reminded you of Dead Alive?

Apart from that, The Substance fulfilled every one of the high hopes that I formed for it based solely on the prospect of a body horror riff on The Wasp Woman. This movie is so much more than that, though, revealing layer upon later of additional interest as the story wears on. Nevertheless, I’ll start with the Wasp Woman parallels, because they’re the most immediately attention-getting. Like Roger Corman’s old mad-science were-bug flick, The Substance is so overt about its treatment of the intersection between sexism and ageism that it’s barely even subtext anymore. When the opening montage sketching out the highlights of Elizabeth Sparkle’s career leads straight into Harvey discussing— over his cell phone, in the bathroom— his plans to put her out to pasture, the unfairness of the whole thing is right up in our faces. After all, the network boss is no spring chicken himself, and despite all the splitting, warping, melting, and exploding flesh we’ll eventually see in this movie, The Substance’s most viscerally revolting image remains a succession of ever-tighter closeups on Harvey eating shrimp. Nobody ever suggests that he’s too old for show business, though— hell, nobody even suggests that he’s too old to keep dressing like Liberace’s heterosexual evil twin! But again like The Wasp Woman, The Substance is less concerned with that tilted playing field per se than with the things women are willing to do to themselves in the hope of circumventing it. With that in mind, it’s worth looking closely at the titular biochemical and the largely invisible enterprise behind it. This outfit, whoever they are, aren’t just ethically shady, like the fad diet, nutritional supplement, and plastic surgery industries. The Substance is an outright scam, a product that fundamentally doesn’t do what its marketing claims it does. True, it creates a younger, more perfect clone of the user, but since the older, less perfect customer gets to experience being that other person only once before the switching process permanently separates their mentalities, the whole program is the cruelest and most monstrous sort of bait-and-switch. Indeed, the only reason why Elizabeth is able to follow her alter ego’s activities at all is because Sue capitalizes on Elizabeth’s residual proximity to fame to become a celebrity in her own right.

One has to ask, though, to what extent the pair’s dual celebrity is itself the decisive factor in turning Elizabeth’s and Sue’s strange relationship in so mutually destructive a direction. We’ve already observed the array of pressures tempting Sue to abuse Elizabeth, but what isn’t as immediately obvious is that the spinoff persona’s behavior almost certainly reflects the capacity for ruthless self-interest that enabled the young Elizabeth to get where she got in the first place. Elizabeth’s increasing resentment of Sue, meanwhile, is driven not only by the gnarled joints, twisted bones, and bloated soft tissues that so often greet her upon the reactivation of her old body, but also by the mere fact of the girl so publicly enjoying everything that she herself used to have. So who knows? Maybe if neither one of them were ever famous, they wouldn’t have wound up at each other’s throats so quickly.

The point about Sue recapitulating Elizabeth’s own rise to stardom leads me back to what I said before about The Substance’s Jekyll-and-Hyde angle creating a temptation to read her as a bad side made manifest. In fact, though, Sue is something much more interesting and disturbing than that. She’s Elizabeth’s younger self, with all the qualities, both good and bad, that that entails. She’s the fitter, stronger, more adaptable, more adventurous, more outgoing Elizabeth, sure. But she’s also more reckless, more impulsive, more insecure, more easily swayed. She’s the Elizabeth who hasn’t yet learned to count the cost of bad decisions, who can’t hear herself think half the time over the roaring of her hormones, who can’t fully believe, deep down, that she isn’t invincible and isn’t going to live forever. Most of all, she’s the Elizabeth who hasn’t yet managed to internalize the fact that other people are real— including her own older self, hidden away in that secret chamber. Sue, in other words, is a walking reminder to us old geezers that being young wasn’t everything it’s cracked up to be.

The flipside of that, of course, is that being old, in a lot of ways, objectively sucks. This, to me, is where The Substance becomes most interesting and effective, because Coralie Fargeat plainly recognizes that there isn’t one person in the world much over 40, sex or gender notwithstanding, who doesn’t fantasize from time to time about what this movie’s miracle drug claims to offer, and who wouldn’t still fantasize about it if all the world’s anthropogenic unfairness and injustice went away tomorrow. No matter what the self-help books might say, age is a great deal more than a number. It’s also an ever-expanding list of things you can’t do anymore because this or that piece of your body just doesn’t work the way it used to— and what might be even worse, it’s the certainty that you have more life behind you than ahead of you, even in the best-case scenario. Note that Fargeat never overtly editorializes about this stuff the way she does about the raw deal Elizabeth gets from Harvey. It never comes up in dialogue, nor does it get a visual symbol, the way Sparkle’s cracked and discolored Walk of Fame star comes to stand for the state of her showbiz career. There’s no need for any of that, because the mere physical contrast between Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley does the job all by itself. Over the course of this film, we spend a whole lot of time looking at the two actresses’ naked bodies, studying the differences between them in minute detail. Partly this is that Male Gaze you always hear about (wielded remarkably well by a woman, I must say), covetously worshipping beauty and contemptuously scorning its absence, and in that mode it serves Fargeat’s polemical aims. But on another, more basic level, it’s a straightforward acknowledgement that Qualley is now as Moore was once, and that as Moore is now, Qualley someday shall be. It’s a mute yet eloquent testimonial to what time is slowly taking away from all of us, every second of every day. I think it’s important, too, from this perspective, that the Substance user who turns Elizabeth on to the program is a man. In the 21st century, men have unattainable beauty standards of our own to drive us batty, and incipient decrepitude has never been any fun for us, either.

All the foregoing is, among other things, a roundabout way of saying that The Substance has a tremendous amount riding on its two lead actresses. Both are phenomenal. Qualley was an unknown quantity to me, so my reaction to her was merely that of seeing someone I’d never heard of before truly bringing it. Sue is the kind of person whom people often describe as a force of nature (which is ironic, because nature had no hand whatsoever in her creation), but she’s also little more than a kid, and her behavior increasingly reflects that as the film wears on. Qualley conveys both aspects ably, but where she shockingly excels is in the monster-suit performance required of her by the fourth act. The moment when that thing puts on her earrings is one of the best bits of purely physical acting I’ve seen in a while. Moore, on the other hand, I remember well enough from the 90’s, when she was a ubiquitous presence in movies that mostly didn’t interest me, but which I often ended up seeing anyway just because my family subscribed to cable TV. I never would have guessed she had a performance like this in her! Just raw and hurt and desperate and angry, and ultimately downright crazed, it’s enough to make me hope that other makers of horror films who have big-time has-been money at their disposal are paying attention. Moore is pretty fucking great in her monster suit, too, even if Qualley gets to have more fun with that phase of the film. The Substance was made at the behest of the streaming service Mubi, so heaven knows whether it’ll ever be seen again by non-subscribers now that it’s on its way out of theaters, but it might be worth burning a trial signup just to see it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact