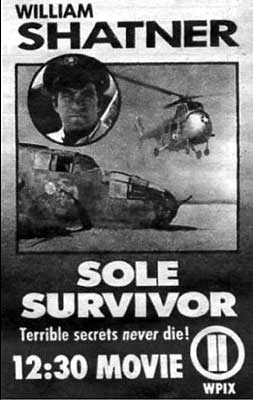

Sole Survivor (1970) **˝

Sole Survivor (1970) **˝

The first time I heard the term, “magic realism,” I felt like the old man in Raising Arizona when the bank robbers burst in yelling, “Freeze! Everybody get down on the ground!” If’n there’s magic, that don’t seem very realistic. And if’n it’s realism, that don’t sound very magical. All the attempts to define it that I encountered, meanwhile, seemed either slippery or suspect, like their main objective was less to delineate the parameters of a genre than to give people who subscribed to The New Yorker permission to enjoy fantasy fiction. What finally made it snap into place for me was the realization that I’d been exposed to hours and hours of magic realism during my childhood, although nobody had called it that at the time. Magic realism is “The Twilight Zone.” Not the classic episodes, mind you. Not airplane gremlins or cookbook aliens or children throwing temper tantrums with the power of a tiny, angry god. No, magic realism is those other “Twilight Zone” episodes, the ones in which ordinary, small-town people go about their ordinary, small-town lives until one day something inexplicable happens to change the way they look at the world. The inexplicable thing isn’t scary or threatening or even especially wondrous; most of the time, it doesn’t even permanently change anybody’s life directly. But in the aftermath, the surly old asshole learns to stop being one of those, the young divorcee finds her capacity to love reawakened, the disapproving father reconciles with his underachieving son, and Jesus H. Christ, I’m going into insulin shock.

Not all of those “Twilight Zone” episodes were bad, though, and although I personally don’t have a lot of use for magic realism most of the time, television writers have often found it very useful indeed. For decades, it was arguably the ideal mode for telling fantastical stories on the small screen, for a variety of reasons. The genre’s presumed setting is by definition the world we know, so there’s no need to spend a fortune on exotic production design. Magic realism isn’t action-oriented, so you can forget about the expense and hassle attendant upon stunts and pyrotechnics. More often than not, you can get by without using a single special effect. And perhaps best of all in the days of omnipotent Broadcast Standards departments, magic realism does not inherently compromise its effectiveness by steering clear of subject matter that pisses off prudes. Case in point: the 1970 made-for-TV movie Sole Survivor. Coming very close to the beginning of that decade’s telefilm boom, Sole Survivor gets all the production value it needs from a dry lakebed in Southern California and a B-25 from the Air National Guard’s junk yard. And although it’s designed as a suspenseful ghost story, it never has to concern itself with whether or not it’s scary, because the ghosts are the viewpoint characters.

In the trackless Libyan desert, some 200 miles south of Benghazi, lies the broken wreck of the B-25J medium bomber dubbed Home Run by its crew. The plane itself affords the only shelter for as far in any direction as the eye can see, and at first it seems reasonable that five of the men who flew in her— Mac the pilot (Patrick Wayne, from Revenge and Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger), copilot Tony (Lou Antonio), Brandy the tail-gunner (Dennis Cooney), and a couple of guys whose roles I didn’t catch, by the names of Gant (Lawrence Casey, of The Student Nurses and The Daughter of Emmanuelle) and Elmo (Brad David, from Stripped to Kill and The Candy Snatchers)— have preferred sticking close to “home” in the hope that someone will fly over and see them to gambling on a death-march across the desert. But then it comes out in conversation that the airmen have been at this for eighteen years. How is that even possible? No aircraft could have been that well provisioned, and in any event, not one of these guys looks a day over 30. Yeah, well, you’ll notice that I’ve pointedly avoided using the phrase “survivors of the crash” thus far. The Home Run is haunted, and the reason its unquiet spirits watch the sky so eagerly is because they believe that the discovery of their bleached bones will finally free them from this limbo, and enable them to move on to the next world. If that’s true, then today is their lucky day. A recreational pilot is out over the desert, steering his little twin-engine puddle-jumper along exactly the right course to encounter the bomber’s carcass. Once that pilot gets the word out, a team of investigators will be sent to the crash site, and all the ghosts will have to worry about then is moaning in the right hollows and rattling the right chains to point the searchers toward their unknown graves.

Or at any rate, that’s what Mac and the boys think. In fact, it’s a little more complicated than that, and the man they have to thank for it is their old navigator and bombardier, Russell Hamner (Richard Basehart, from City Beneath the Sea and The Island of Dr. Moreau). The reason why Hamner isn’t with his comrades at the crash site is because he bailed out over the Mediterranean Sea, just minutes after the Home Run took her ultimately fatal hit to the starboard engine. Mac had given no order to abandon ship at that point. In fact, the last order he gave Hamner was to compute the shortest practicable course to safety on the Libyan coast. Hamner had no such faith in Mac’s ability to keep the wounded bird together that long, so he jumped instead; at least he had the courtesy to lighten the load for the others by emptying the Home Run’s bomb bay on his way out. Arguably the navigator’s instincts were good, cowardice notwithstanding, because he survived not just the crash, but the entire war. When he was picked up by an Allied ship a day or two after bailing out, he told his rescuers that the Home Run must have crashed at sea— and thus it was that no search of the desert was made at the time, when it might have done Mac and the others the most good.

Word of the Home Run’s discovery creates a ticklish situation for the Air Force, because Hamner is still in the service. Indeed, he’s now a brigadier general. Standard operating procedure requires that the case be reopened long enough for the downed plane to be examined, and evidence at the scene to be compared with the survivors’ accounts. The mere circumstances under which the Home Run was found are enough to make Hamner’s old testimony smell rather fishy, and everyone involved knows it. However, everyone involved also knows how foolish the men who pinned that star onto Hamner’s collar are going to look unless every word of it is deemed to be true. The investigation is entrusted to Lieutenant Colonel Josef Gronke (William Shatner, from American Psycho 2 and Impulse) and Major Michael Devlin (Vince Edwards, of Cellar Dweller and The Fear), two men with starkly divergent views on how to carry it out. Gronke doesn’t like to make waves, but it’s going to be hard to touch this case without triggering a tsunami. If it were up to him, the investigation would be made as hurriedly as possible, and the report written up in a pro-forma manner. No need to wreck a general’s career over something that happened eighteen years ago, right? Devlin’s highest loyalty, on the other hand, is to the truth, however uncomfortable it may be. He recognizes at once that Hamner is shady, and he’s quick to spot a dozen ways in which the story doesn’t add up once he, Gronke, the general, and the rest of the investigation team have a chance to look over the Home Run in person. The ghosts of the flight crew, for their part, just as rapidly recognize Devlin as their natural ally, but what exactly can five dead men do to aid their friends among the living?

Frankly, I’m astounded that Rod Serling’s name is nowhere to be found in Sole Survivor’s credits. This story is right up his alley, and it isn’t as though he was a stranger to the telefilm medium. Beyond that, the second season of “The Twilight Zone” included an episode that was almost the reverse of this story. It had the sole survivor of a wartime bomber crash haunted by guilt-induced delusions in which he was doomed to live alone in the Sahara Desert, sheltered only by the wreck of his plane and with only the graves of his crewmates to keep him company! Sole Survivor even duplicates a few of Serling’s regular tics, like the overwrought portrayal of the bomber crew’s ostensibly admirable simplicity, and an ending that is neither precisely a twist nor precisely a downer, but partakes somewhat of both. A Serlingesque skepticism toward systems and authority figures is in evidence, too, counterbalanced by a similarly Serlingesque faith in the power of individual integrity to win out in the end. Indeed, viewers who missed the title and opening credits would have little beyond the running time and the color cinematography to clue them in that this wasn’t a “Twilight Zone” episode.

There’s both good and bad implied in that statement, of course. As the film wears on, Sole Survivor starts showing its small-screen origins a little too clearly, even despite the unconventional setting and the on-location shooting. Although the wrecked bomber and the hellish desert are initially impressive, it soon becomes uncomfortably obvious how little else we’re seeing. And the flashbacks to the Home Run’s last mission are pretty sad affairs, however much credit is due to the production simply for attempting them in the first place. The emphasis on adversarial quasi-judicial proceedings often gives Sole Survivor the flavor of a courtroom drama without a courtroom, and you should all know by now the strength of my prejudice against those. But like the most creative episodes of “The Twilight Zone,” Sole Survivor proceeds from a brilliant rethinking of a common trope. How often do you see a “ghosts expose the misdeeds that led to their deaths” story told from the ghosts’ point of view? How often are you asked to imagine what it’s like to be that kind of ghost, trapped between one existence and the next unless and until somebody follows just the right clues to discover your remains, while possessing only the most limited power to steer events in that direction? If this is how it is, then no wonder the typical fictional haunting seems so vengeful! Most ghost stories are about the past imposing itself upon the present; Sole Survivor is the only one I know of in which the present has the past completely at its mercy.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact