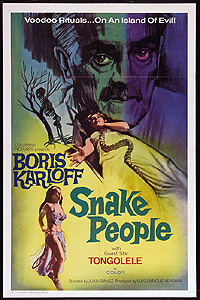

Snake People/Isle of the Snake People/Isle of the Living Dead/La Muerta Viviente (1968/1971) -**

Snake People/Isle of the Snake People/Isle of the Living Dead/La Muerta Viviente (1968/1971) -**

Those of you with long memories may recall me saying, in my review of Die, Monster, Die!, that that movie, lackluster as it was, at least didnít give star Boris Karloff occasion for the sort of embarrassment which must have afflicted Bela Lugosi and Lon Chaney Jr. in connection with the films they made at the ends of their careers. Well now weíre going to take a look at a movie that does. By 1968, Karloff was 81 years old and mostly confined to a wheelchair. But despite his venerable age and failing health, he continued to work practically up until his death early the following year. His last acting gig was a succession of Mexican-made horror flicks shot by the border-spanning team of Jack Hill (whose other notable credits include such films as Coffy and Spider Baby, or The Maddest Story Ever Told) and Juan Ibanez. On all four pictures, Hill would direct Karloffís scenes up in California, while Ibanez would tackle the rest of the production back home; Iím really not sure who ran the show when the time came to consolidate the two crewsí work. Two of the movies in question were completed and released during their aged starís lifetime, while the remaining two languished for years, unseen by audiences whose lives were probably infinitesimally improved for having no knowledge of them. Snake People is one of the latter pair, and I can easily see why its producers were in no hurry to get it into the theaters, even in Mexico.

On the island of Korbai, a remote French colony in the South Pacific, the natives practice foul and unholy rites in the dead of night. And so, as we shall soon see, do some of their European overlords. One such man (QuintŪn Bulnes, from The Living Coffin and Curse of the Doll People) goes with a sinister-looking dwarf (Santanůn, who spent most of his career on surreal Mexican childrenís films like Little Red Riding Hood and the Monsters and The Happy Musketeers) to an isolated cemetery, where the dwarf uses voodoo magic to raise the body of a pretty girl from the dead. And lest you have any doubt about how the gaunt, haggard Westerner plans to make use of his comely zombie slave, the man immediately takes the dead girl in his arms and begins kissing her. Manó necrophilia, a dwarf, and chicken-snuff footage, all in the first scene! Whatever else we may say about the filmmakers, they sure werenít screwing around!

It is precisely because of that sort of behavior that the French authorities have decided to dispatch an inflexible captain of gendarmes by the name of Pierre Labiche (Rafael Bertrand, from The Black Pit of Dr. M and The Fearmaker) to Korbai. And it is precisely because of men like the hard-drinking Lieutenant Andrew Wilhelm (Charles East, of Tintorera and Guyana: Cult of the Damned)ó the islandís former chief of policeó that temperance activist Annabella Vanderberg (The Curse of the Crying Womanís Julissa del Llano, whom Hill and Ibanez also used in The Fear Chamber) has followed behind Labiche. Well, that and the fact that her uncle, Karl von Molder (Karloff) happens to be the richest and most influential man on the island. That last part also explains why von Molder is the first person Labiche wants to see when he reaches Korbai; the new top cop figures the old man could make his job of cleaning up the place easier by letting himself be seen throwing his weight around in favor of law and order.

Both Vanderberg and Labiche are in for a disappointment, however. For one thing, von Molder is a drinking man himself, and while he seems willing enough to indulge Annabellaís hobby, itís also obvious that he sees his cooperation with her anti-alcohol activism in precisely those termsó as the act of a doting old uncle indulging his nieceís interest in something he doesnít take remotely seriously. And when Labiche turns to him for aid on his mission, the old man tells him in no uncertain terms that it is a bad idea to interfere with the islandersí customs, no matter how offensive they may seem to Parisian sensibilities. For though von Molder may secretly scoff at temperance movements, he takes the local voodoo cult very seriously indeed. In fact, so impressed with it is he that he has come out of retirement to make a scientific study of the subject, which has convinced him that the paranormal powers the natives ascribe to their priests are entirely real. Furthermore, von Molder contends that those powers lie dormant in every human mind, and that the islandersí magic is merely a convenient way to awaken them. As the old scientist explains this to Vanderberg, Labiche, and Wilhelm, he ushers them into his laboratory, where he demonstrates that he has succeeded in cultivating a small degree of telekinesis within himself. A much more impressive demonstration follows when von Molder calls in his maid, Kalea (stripper-turned-actress Yolanda Montes, better known by her old stage name, Tongolele), and has her set a tray of kindling alight solely with the power of her mind.

That there is our first hint that von Molder may also be the high priest Damballah of whom the islanders speak with equal measures of reverence and fear, for Kalea is a major figure in the voodoo cult herself. Together with the dwarf we saw earlier, she presides over observances dedicated to the god Baron Samedi, essentially playing parish priest to Damballahís bishop. (And as if you needed to be told this, her duties consist to a great extent of showing off the moves that made Tongolele the best-known exotic dancer south of the Rio Grande.) The second hint that von Molder and Damballah are one and the same comes when we are introduced to Klinsor, the head overseer of von Molderís estate. You guessed itó heís the skinny guy who likes to get it on with the undead! At this point, I think we all feel fairly confident as to the real reason why von Molder advises Labiche not to go meddling with local religious traditions.

Donít you imagine that Labiche has any intention of following that advice, however. The captain is a man on a mission, and if you think heís just going to tell his bosses back home that he decided not to stamp out voodoo on Korbai because the neighborhood squire counseled against it, then youíre even crazier than Klinsor the corpse-fucker. Labiche cracks down hard, but it isnít long before he realizes what a fight heís got on his hands. Curses that fill the captainís house with disappearing snakes are the least of the weapons at the cultís disposal; before all is said and done, Labiche and his men will also come up against cudgel-armed thugs, the walking dead, and even an elite assassination squad of crazed cannibal women! Meanwhile, Kalea and the dwarf will set their sights on Annabella Vanderberg, who seems to fit the bill perfectly for a human sacrifice at the upcoming invocation of Baron Samedi.

Youíd think a movie like this would be a sure thing. I mean, look at it: voodoo, zombies, cannibals, necrophilia; torture scenes, human sacrifice, a dream sequence involving autoerotic lesbianism (Annabella Vanderberg, under Kaleaís influence, dreams of making out with herself); a cast that features an ex-kiddie matinee midget, the Blaze Starr of Latin America, and a visibly dying Boris KarloffÖ But somehow Snake People never really comes together. For one thing, way too much time is squandered on the studiedly improbable romance between professional prude Vanderberg and roguishly decadent wastrel Wilhelm. Itís a silly plot thread, and itís boring too. Another big problem is that the numerous black magic ceremonies (and while Iím on the subject, we might justly ask how the inhabitants of an island in the South Pacific came to practice a religion thatís a mish-mash of Caribbean voodoo, South American brujerŪa, and Mycenaean snake veneration) serve more as interruptions to the story than as integral parts of it. Every so often, the movie just stops in its tracks to devote five minutes or so to Kalea doing an old Tongolele dance routine while the dwarf ritually slaughters a chicken or billygoat, or some such thing.

Nevertheless, Snake People does have its moments. The recurring theme of Kalea walking in on Klinsor and one of his zombie paramours and de-animating the dead girl before the frustrated pervert can get any real action is an impressively bold venture in bad taste. The dwarf priestís death scene is a hoot, partly because of Santanůnís remarkably misguided performance, and partly because his killer has absolutely no conceivable motive for doing him in. But my favorite moment of all comes at the climax, when Labiche and Wilhelm intervene to stop von Molder from sacrificing Annabella to Baron Samedi. All through the film, it hasnít really been Karloff hidden inside that Damballah getup, but for this one scene, Hill shot some footage of the old star speechifying in costumeó in a tight enough closeup that it isnít immediately obvious that Karloff is both sitting down and on a different set from that used in the rest of the scene. What is immediately obvious is that his Damballah costume isnít the same one that the double was wearing during the Mexican shoot! Then itís back to the double again for the remainder of the sceneó the effect is the same as that of the more famous toggling between Bela and Not-Bela in Plan 9 from Outer Space. Better still is yet to come, though, for when the time came to dub von Molderís final lines over Ibanezís footage of the characterís death, Karloff apparently wasnít available (Too sick? Too dead?), and we are treated to what must certainly be the single worst Boris Karloff impression ever to issue from the mouth of man. I donít know that itís necessarily worth it to sit through the rest of Snake People just to witness that one astounding scene, but I do know that Iíve watched worse movies for less in my time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact