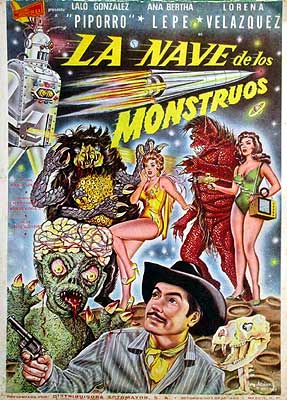

The Ship of Monsters / La Nave de los Monstruos (1960/1961) -***

The Ship of Monsters / La Nave de los Monstruos (1960/1961) -***

As one or two of you may recall, I have an indefensible fondness for Devil Girl from Mars. I’m not saying it’s a favorite of mine, but I like that mid-50’s British sci-fi turkey a lot more than it ever did anything to deserve. For everyone else who rightly feels let down by that film, however— everyone who protests that it’s shoddy and stupid and half-assed, and worst of all, dull— allow me to recommend its surprisingly close conceptual counterpart from Mexico, The Ship of Monsters. The Ship of Monsters is everything that Devil Girl from Mars should have been, but wasn’t. It’s still shoddy and stupid, mind you, but its creators put their whole asses and then some into making it so, and it’s never, ever dull.

Venus has problems. The last man on the planet died recently from the after-effects of a nuclear war some unspecified time in the past, seemingly dooming the Venusian people to extinction. But the Regent of Venus (Consuelo Frank, of A Macabre Legacy and Queen Doll) has an audacious plan to salvage the situation. She means to send two of her bravest and most talented subjects— a native Venusian woman called Gamma (Ana Bertha Lepe, from The Volcano Monster and Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp), and Beta (Lorena Velazquez, from Doctor of Doom and The Shame of the Sabine Women), an immigrant to Venus hailing originally from Ur, the Planet of Shadows— out into space aboard an interstellar rocketship. Their mission will be to collect male specimens of every sapient species that can be found, in the hope that one of them has what it takes to father a new hybrid Venusian race. Of course, the severity of her people’s crisis is such that the Regent doesn’t care very much whether or not the beings in question want to participate in an interplanetary breeding program, and Gamma and Beta are authorized to resort to force if need be.

We’re never told how long Gamma and Beta spend gallivanting across the galaxy, but by the time the opening credits have wrapped up, they’ve collected four breeding candidates, plus an ancient and extremely helpful robot called Torr (the sharp-eyed will recognize the suit from Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy), which was built by a species that destroyed itself and its entire ecosystem in a war even more apocalyptic than the one on Venus. None of the captive males look terribly promising, to be perfectly honest, although they certainly do buck hard against the low-budget sci-fi trope whereby every alien of human-like intelligence can be counted on to look like one of us, but with funny-colored skin or a strange-looking forehead. Tagual, Prince of Mars, is a rugose, dwarfish creature with an enormous head and a throbbing, exocephalic brain. Uk, King of the Fire Planet, is a hulking cyclops covered all over with stony scales, as violent as he is arrogant, and as arrogant as he is stupid. Utirr of the Red Planet (which is apparently someplace distinct from Mars) is a vaguely humanoid spider-thing with extensible limbs and a venomous bite, who considers any being less physically powerful than himself to be on the menu. Ironically, the best bet of the bunch might by Zok, representative of a nameless, bodiless race, because his people appear to be capable of animating the dead remains of other species. He himself spends the movie possessing what appears to be the skeleton of a puma. Breeding with his sort would mean acquiring a taste for necrophilia, but at least the Venusian women could be certain the genes would match!

Now it happens that none of those guys are happy to have been abducted from their homeworlds for use as brood studs, and whatever beauty standards they maintain back home plainly don’t extend to include Miss Mexico pageant winners (which both Ana Bertha Lepe and Lorena Velazquez were, in 1953 and 1960 respectively). The captive males grow increasingly rowdy as the rocketship nears its home port, and Beta is forced to freeze the lot of them into suspended animation when one of the main engines seriously malfunctions. Can’t risk any of them breaking loose while she and Gamma are fixing the propulsion system, after all. An extravehicular excursion establishes that the damage is too serious to be repaired in space. The ship will just have to limp to the nearest suitable landing site and set down. The only such place within reach is a planet which the Venusians have never visited, or even given much thought to, despite its close proximity to their own. Torr, whose creators had explored and catalogued the place, identifies it as Antarssi 1352, but you and I know it as Earth.

Meanwhile, in Chihuahua, singing cowboy Laureano Atreviño Gomez (then-popular Mexican comedian Lalo “Piporro” Gonzalez) is belting out his generalized romantic longings on the trail to his favorite watering hole. Soon after he arrives at the saloon, we see that Gomez is a regular Don Casamonjes, regaling his fellow drinkers with flagrant lies about his supposed adventures in the surrounding, still-untamed countryside. There’s one man among Gomez’s listeners (Manuel Alvarado, from House of Evil and The Skeleton of Mrs. Morales) who is not amused by his confabulations, though, and for a minute there, it looks like Laureano is going to get pressed into a quickdraw contest against the great, big grump. Gomez wriggles off of that hook partly by buying his antagonist a drink, partly by flattering him in terms just as obviously phony as his earlier tall tale, and partly by conducting his side of the abortive duel in a manner guaranteed to persuade anyone that he’s not man enough to be worth shooting. There’s considerable irony in that, for Gamma and Beta will come to find Laureano’s manhood the most satisfactory they’ve encountered on at least six planets.

Yes, Gomez is the first human whom the Venusians encounter after making landfall on Earth, and although all concerned are mainly just confused by that initial contact, a subsequent visit by the alien astronauts to the ranch where Laureano lives with his much younger brother, Chuy (Heberto Dávila Jr.), and a variety of farm animals convinces Gamma and Beta alike that they’ve found on Antarssi 1352 what they’ve been looking for all along. Indeed, they’ve found rather more than they were looking for, because even before Venus became a women-only planet, its people (and don’t tell me you didn’t see this coming) knew nothing of love. Gomez is more than happy to demonstrate the unfamiliar concept to his extraterrestrial visitors, and Gamma and Beta alike return to their ship absolutely smitten with him. Torr falls just as hard as his carbon-based shipmates, too— but in his case, it’s Laureano’s jukebox that steals his fuel pump.

The trouble with being smitten is that smitten people often don’t want to share, and the Regent didn’t send Gamma and Beta out into space just so that they could get laid. The Venusian women have a bigger problem on their hands than burgeoning mutual jealousy, though, because (and there’s no fucking way you’ll see this coming) when screenwriters Alfredo Varela and José María Fernández Unsáin say that Beta comes from the Planet of Shadows, what they really mean is that she’s a vampire. Vampires, of course, are even less apt to share than jealous women, and when Beta figures out just how slim are the chances of Gomez being allocated to her once the mission is complete, she devises one hell of a Plan B. If going back to Venus means giving up Laureano, then not only will Beta stay right here on Earth, but she’ll also turn loose the increasingly pissed off space monsters in the cargo hold to help her conquer the planet, so as to make absolutely sure she gets what she wants when all is said and done. Gomez, in other words, is about to find himself a key participant— for real— in the kind of outlandish adventure that he habitually bullshits up for the entertainment of his fellow drunkards at that saloon. And what’s more, there’s an excellent chance that there’ll be space pussy in it for him in the unlikely event that he survives!

As the presence of Lalo Gonzalez in the cast ought to imply, The Ship of Monsters was intended as a comedy. Consequently, in contrast to roughly contemporary Mexican oddities like Monster or The Brainiac, The Ship of Monsters is fully aware of its own absurdity, and revels in it from start to finish. On the surface, this movie is as junky and dumb as any straight-faced film along the same lines, with cheesy yet overdone monster suits in the “best” Paul Blaisdell tradition, space flight footage stolen shamelessly from Pavel Klushantsev’s The Road to the Stars, the most staggering out-of-nowhere heel turn I’ve seen in years, and last but by no means least, a pair of statuesque space girls whose costumes belong on the same Miss Mexico stage where the casting director found the actresses playing them. Look closer, however, and you’ll see that the filmmakers have snuck some genuine cleverness in amid all the typical ludicrous crap. The screenwriters, to all appearances, were as thoroughly conversant as the target audience with all the Girl Planet and Horndogs from Outer Space movies of the decade just past. Notice, for example, that by rounding up a quartet of rubber-suit monsters (or more accurately, three rubber-suit monsters and a rickety skeleton puppet) for their breeding program, the Venusian women have stood I Married a Monster from Outer Space on its head. Torr’s happily-ever-after with Laureano’s jukebox is simultaneously the ultimate reductio ad absurdum of the “What is this thing you call ‘love’?” trope and, in a twisted way, about the most logical interpretation of it that I can remember seeing. And although it’s impossible to tell how much of this was intended, and how much was a happy accident, any comparison between the reaction to their mission that Gamma and Beta get from Laureano, and that which greets Nyah in Devil Girl from Mars, functions as a pitch-perfect gag on the respective stereotypes about Mexican and British attitudes toward sex and romance.

It’s worth pointing out, too, what a charmingly unusual hero for this sort of movie Laureano Gomez is. I gather that, like many comic actors of the period, Lalo Gonzalez had a stock type to which his characters tended to conform, but I don’t know enough about his career to say with any certainty whether, or to what extent, The Ship of Monsters fits into the pattern. What I can say is that as Laureano, Gonzalez squarely hits one of the hardest targets in comedy, the lovable rascal. An incorrigible bullshitter and a coward posing as a macho man, Gomez is at once an extremely unimpressive figure and the sort of protagonist who could wear out his welcome in seconds if handled with anything less than the utmost finesse. I don’t know how Gonzalez does it, but he manages to seem disarmingly self-deprecating even— indeed, especially— when Laureano is puffing himself up most implausibly. Mind you, he gets plenty of help from the dialogue, which is snappy, sharp, psychologically astute in a cockeyed kind of way, and often remarkably risqué for the turn of the 60’s. I think maybe the key to understanding what makes Laureano tick is a line from the song he sings en route to the saloon: “My horse will tell you that I never lie.” It isn’t just that his assertion of faultless honesty is itself an obvious falsehood— it’s a falsehood so obvious that not even a child could be deceived by it. Laureano may be completely full of shit, but there’s no malice in his lying. Similarly, his lack of courage extends only to bravery of the ordinary sort. Present him with an opening to bullshit his opponent into submission, and he’ll take on anyone up to and including a vampire woman from the Planet of Shadows!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact