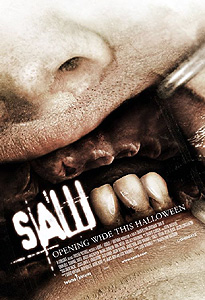

Saw III (2006) **

Saw III (2006) **

Iíll give Saw III this much credit: it doesnít follow its predecessorsí pattern of fucking up a good and engaging story with a bullshit surprise ending. Unfortunately, thatís because the bullshit surprise ending is just about the only thing that renders Saw III even slightly interesting. The information revealed in its incontinent orgy of climactic flashbacks turns the Saw series thus far into something close to the perfect case study in the folly of the Shocking Twist, for were these moviesí creators not so committedly wedded to the technique, Saw and its first two sequels would form an extraordinarily cohesive and satisfying story arc. If writers Leigh Whannell, James Wan, and Darren Lynn Bousman had earned the revelations and reverses on which they placed such unbalanced emphasis with honest character development, careful foreshadowing, and solid narrative logic, I would be right up in the forefront of the Saw filmsí cheering section. Instead, though, the aforementioned gentlemen (Whannell and Wan probably more so than Bousman) are incorrigible cheats, and their cheating becomes more brazen with each successive installment. The original Saw confined most of its deck-stacking to a villain whose abilities seemed hugely disproportionate to his opportunities for acquiring them, especially in comparison to the more or less realistic handling of all the other characters. Saw II went further, giving us a betrayal among the protagonists that flew directly in the face of every piece of evidence we had about either the Jigsaw Killer or the woman who turned out to be his accomplice, and then hastily erecting a rickety scaffolding of flashbacks in the hope of holding that towering idiocy aloft for the few minutes remaining until the closing credits. Saw IIIís mendacity toward its audience is simply mind-boggling. This time, the filmmakers keep what ought to be the whole second act under wraps, allowing the movie to wander in pointless circles for a good half of its length simply for the sake of leaving some rug to pull out from under us at the conclusion.

Now where were we? Ah, yesó thatís right. We were with Detective Eric Matthews (a returning Donnie Wahlberg), as he emerged from a sedative haze to find himself shackled to a pipe in a familiar skanky-ass bathroom, while the Jigsaw Killerís avid apprentice, Amanda (Shawnee Smith again), shut the door on his prison and left him alone to find a way out of the trap. (Incidentally, this makes three confinees to that bathroom who fail to notice that although their chains may be impervious to attack with a standard hacksaw, the pipes to which those chains are secured are so rusty that theyíd probably crumble to dust with three good kicks.) Meanwhile, Matthewsís former Other Woman, Detective Allison Kerry (still Dina Meyer), was sending Rigg (still Lyriq Bent) and his SWAT team to completely the wrong house to effect a rescue that was already several hoursí worth of irrelevant. Saw IIIís resumption of this scenario would seem at first to indicate that itís going to devote a substantial amount of its attention to resolving the multitude of interesting issues raised by the last movieís duel of wits between Matthews and terminally ill serial killer John Kramer (Tobin Bell, back again too). We all know by now that we canít have nice things, though, right? Sure we do. That being the case, Matthews disappears from the film almost immediately, to be seen again only during the aforementioned concluding series of flashbacks that ought to have been the second act. Kerry, for her part, makes no visible effort to locate Matthews in the face of this setback. She merely mopes around for a bit before moving along to clean up the mess when a young thug named Troy (Repo! The Genetic Operaís J. Carose) gets blown to bits in a public school classroom after hours under most Jigsaw-like circumstances. But as Kerry is quick to recognize, there is an important sense in which this crime scene doesnít fit the Jigsaw Killerís pattern, however close the superficial resemblance. Kramer goes to great lengths to preserve the fiction that he isnít actually killing anybody, that the proximate cause of his victimsí deaths is their inability to see or unwillingness to do what is necessary in order to survive; the death-trap that claimed Troy, however, was inescapable. Even if heíd satisfied the blatantly unrealistic terms of his ďtestĒ in the blatantly unrealistic amount of time allowed him before the bomb planted beside him went off, the metal door to the classroom was welded solidly into its frame. Either Kramer has made a sudden change in his modus operandi, or this is the work of a copycat killer. Naturally, weíre all, like, fifteen steps ahead of Kerry at this point, and the only surprise weíll experience when Amanda kidnaps her and subjects her to a similarly corrupted version of the Jigsaw treatment will stem from the very small percentage of the movieís running time that has thus far elapsed when the detective succumbs to a scaled-up full-body version of Kramerís oft-employed Headsmash-o-Matictm. I mean, what the fuck is this movie going to be about now that both copsí stories have turned out to be dead ends with easily an hour yet remaining on the clock?

Believe it or not, itís going to be about Amanda and the weirdly filial relationship that she has developed with John Kramer. This is an odd direction for the series to take, because it means suddenly treating the villains as protagonists at a time when we donít really have enough information about them (or rather, enough of the right kind of information) for the shift in focus to succeed without a massive exposition dump. Weíll get one of those, too, but the tyranny of the twist ending requires that it exposit only the things we donít need to know. Instead of delving into the psychological enigmas surrounding the origin of Amandaís apprenticeship to Kramer, Bousman, Wan, and Whannell merely waste everyoneís time with unedifying flashbacks that retroactively extend the killersí collaboration all the way back to the events of the first film.

Focal inversion or no, this is still a Saw movie, and the fanbase is going to be mighty peeved if thereís no high-stakes psychology experiment at the center of things. Of course, Amanda already killed off the two logical test subjects, so the filmmakers must now introduce new ones in the form of Dr. Lynn Denlon (Bahar Soomekh) and her increasingly estranged husband, Jeff (Angus MacFadyen, of Impulse and Equilibrium). Lynn gets the job because Kramerís cancer has entered the home stretch to victory, placing him in need of someone with serious medical training to manage his symptoms for however many days or hours remain to him. Amanda kidnaps Dr. Denlon, and outfits her with an explosive collar wired up to Kramerís heart monitor; should he flatline before the conclusion of the concurrent experiment (which Kramer describes as the most important of his career), the half-dozen shotgun shells mounted in the collar with their muzzles pointed at Lynnís head will all go off. Jeffís test, meanwhile, is also a bit outside what has been the Jigsaw Killerís main area of interest. Instead of facing a choice between death and something either physically or morally repugnant, Jeff will have to sacrifice the vengeful feelings that have been so important to him ever since his son, Dylan, was killed by a drunk driver three years ago. Denlon isnít alone on his gameboard, you see. Amanda has also kidnapped the driver who killed Dylan (Mpho Koaho), the judge who let the perp off with a wrist-slap sentence (Barry Flatman, from The Dead Zone and Short Circuit 2), and the witness who fled the scene of the accident without giving a statement, critically weakening the prosecutionís case (Debra McCabe). In order to escape with his life from Kramerís trap, Jeff will have to save the lives of the three people he hates most in all the world, or at least make a good-faith effort to do so. If youíre having a hard time seeing how this deadly exercise in forgiveness could hold such importance for Kramer (after all, we donít give a squirt of piss for the Denlons, so why the hell should he?), then youíve already got a head-start on figuring out the twist. Thereís yet a third game unfolding here, about which Kramer hasnít said a word to anybody, and Amanda herself is once again the central player. What? Did you think maybe John Kramer, the Omnipotent Jigsaw Killer, didnít know that his sidekick has been running around doing it wrong?

Actually, yesó thatís exactly what I think, for the simple reason that Amanda herself is Kramerís only imaginable source for information on the design, progress, and outcome of the games she runs on her own. If she wants to keep it under her hat that sheís flouting her mentorís conception of the mission, Kramer has nobody else on the payroll in a credible position to call her out for her duplicity. This enormous central logical lapse is the main reason why I feel compelled to call the conclusion to Saw III a ďbullshit surprise ending,Ē even though itís also the closest thing the movie has to a saving grace. Iím sure Saw V or Saw VI will have some phony-baloney back-dated narrative band-aid to excuse Kramer knowing what Amanda has really been up to all this time, even though his disease has by now reduced him to an inanimate object full of dastardly schemes, but fuck that. Saw IIIís revelation that Amanda had been busy all along handling the jobs too strenuous for a cancer patient did me no good while I was watching Saw, and whatever feeble justifications the writers might dream up two and three sequels down the line for the present load of bollocks do me no good here, either. Furthermore, the folks running this show are not endearing themselves to me by making so obvious a habit of retroactive plot-hole patching. It was fine as a one-time thing when Saw II went back and shored up the weak sections of Sawís foundation. Itís less fine for Saw III to try doing the same for Saw II (as with the new and markedly contradictory version of Amandaís first meeting with Kramer, clearly meant to downplay the importance of her suicidal tendencies), or to spend so much time spackling the remaining cracks in the first film. The repeat performance implies an ďEh, weíll fix it in a flashbackĒ approach to writing which I find most disturbing in light of the fact that Iíve still got three of these movies to go.

Thatís twice now that Iíve called Saw IIIís concluding whammy the good part, and Iím sure youíre all itching with curiosity as to why. The short version is that by turning Kramerís efforts to find and train a successor into a through-line for all three films, the last reel of Saw III renders the series far more coherent than it would be if taken as the sum of its featured victimsí experiences. What we have here is no longer the humdrum stories of Dr. Gordon, Detective Tapp, and the Denlons, nor even the rather more interesting one about Matthews and Kerry. Now, itís the nearly operatic tragedy of a brilliant man driven mad when he gets dealt a shitty hand, who places all his warped hopes for a future he canít personally enjoy in a woman whom he believes to share his madness, but who actually harbors a very different and in some ways antithetical madness of her own. I like that idea, and Iím honestly looking forward to the inevitable Saw remake in 2030 or thereabouts for the chance itíll offer to see the tale told right. Telling it right would mean admitting up front that Kramer is grooming Amanda to be his successor; it would mean a similarly immediate admission that the killers are to be protagonists coequal with whomever their opponents are; and most of all, it would mean dealing fairly with Amanda, putting the big turning points in her character arc in their natural places and giving them their natural dramatic weight, rather than hoarding them for use as fuel for surprise endings that either make no sense or donít actually surprise. Indeed, the fact that Saw IIIís twist isnít surprising (I mean, come onó we knew she was breaking Kramerís rules the moment we saw Troyís egregiously rigged test, and we knew that the filmmakers knew it, too, the moment Kerry mentioned the welded door to her partner) is probably the most dispositive indictment of the approach taken by these first three films. If bending the story this badly out of shape canít achieve the desired aim, then why not cut all the Keyser SŲze crap, and just tell it like it wants to be told?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact