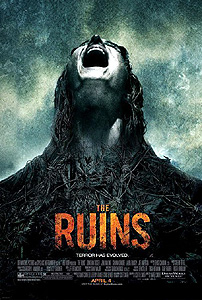

The Ruins (2008) ***½

The Ruins (2008) ***½

It’s been way too long since we had a proper horror movie about a killer plant. I don’t mean a horror spoof like the musical remake of Little Shop of Horrors, nor do I mean a movie about a plant-person— especially if the latter is mounted as an action-fantasy monster flick like Swamp Thing, rather than as a modern take on From Hell It Came. No, I’m talking about a seriously intended fright film in which the inhuman menace belongs strictly to the vegetable kingdom, and the more plausibly plant-like the monster’s nature, the better. The “Lonesome Death of Jordy Verrill” segment of Creepshow comes close, I guess, but even it aims mainly for black comedy. That leaves those of us who occasionally jones for an evil-weed fix with little or no recourse but to go all the way back to the early 60’s for Day of the Triffids and The Woman-Eater. Or so it was, anyway, until the advent of The Ruins in 2008. A generally unprepossessing adaptation of a thoroughly unprepossessing book, The Ruins nevertheless earns distinction by committing itself utterly to a premise that most people would probably laugh off. And as one of the few who do not find the notion of homicidal foliage inherently ludicrous, I can only say it’s about goddamned time.

Jeff (Jonathan Tucker, from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre and Pulse) has just been accepted to medical school. In celebration, he and his girlfriend, Amy (Jena Malone, of Donnie Darko and Contact), have taken advantage of the last few weeks of uninterrupted ease that he’ll enjoy until the end of his residency to spend a relaxing sojourn in Cancun. The couple did not go alone, either, although I get the impression that Jeff rather wishes they had. Along for the ride are Amy’s best friend, Stacy (Laura Ramsey, from The Covenant and one of the altogether too many movies called Venom), and her boyfriend, Eric (Shawn Ashmore, of Blood Moon and Solstice); the cross-couple interpersonal dynamics put me strongly in mind of the vacationing foursome in Dracula, Prince of Darkness, only here it’s the girls who share a pre-existing bond, and the boys who have each judged the opposite pair, and found them wanting. (Incidentally, the personalities and roles of the four central characters have been reshuffled rather drastically as compared to the source novel. What makes that especially noteworthy here is that Scott Smith wrote both versions of The Ruins; it’s tempting to interpret the alterations as signs of what he later decided hadn’t worked in the book.) For Jeff’s part, the great frustration of the trip thus far is Amy’s apparent lack of interest in anything but lounging on the beach at the tourist resort, a narrowness of vision in which she is encouraged by Stacy and Eric. However, on what’s supposed to be the gang’s penultimate afternoon in Mexico, they befriend both a mob of Greek travelers and a German named Mathias (Creep’s Joe Anderson) who has been bumming around Cancun with his brother, Heinrich. It comes out in conversation that Heinrich had picked up a young, female archeologist a day or two ago, and that he is now with her at her dig. Heinrich’s date and her colleagues are excavating a newly discovered Mayan pyramid in a stretch of jungle just a couple hours’ bus-ride away, and Mathias and one of the Greeks— Dimitri (Dimitri Baveas) is his name— will be heading out to meet Heinrich at the site tomorrow morning. Jeff is eager to join in, too, and so, to Jeff’s considerable surprise, is Stacy. Amy underscores her status as the Barbara Shelley of the group with her obvious reluctance, but also like Shelley’s character in the aforementioned Dracula film, she lacks the assertiveness to derail the adventure while she has the chance. Come shortly after 6:00 the next morning, she, Jeff, Stacy, Eric, Mathias, and Dimitri are on their way to the jungle, pausing only long enough for Dimitri to leave a map to their destination for the other Greeks.

Of course, Barbara Shelley was right to want nothing to do with Castle Dracula, and Amy’s instinct that beaches and tequila sunrises are more her speed than Mayan ruins would similarly have been the better part of valor here. The first indication of that is the taxi driver the vacationers hire to take them into the forest after their bus reaches the end of the line. Much like a coachman in a Hammer gothic, the cabby tries at first to warn them away from the ruins (“No, that’s not a good place…”), but $40 American is an awful lot of money in the rural Yucatan. Against his scruples, the cabby takes Jeff’s cash and drives him and his companions to the vicinity of the pyramid. Heinrich’s jeep is there, just as you’d expect to find it, at the point where the dirt road becomes too rough even for a 4x4, and the gang continue on foot. Ominous Hint #2 concerns the path they must follow in doing so; somebody has taken the trouble to camouflage it with a screen of fronds cut from the underbrush, and a pair of Mayan children watch intently as the guys dismantle the obstruction. No sooner have the vacationers set off down the trail than one of those kids races away as if on some urgent business.

The pyramid exhibits a curious mix of modesty and impressiveness when Jeff and the others finally get a look at it. It isn’t a very large edifice, standing just a bit taller and encompassing perhaps twice the volume of a typical rowhouse in an American East Coast city, but it practically radiates antiquity. It’s situated in the middle of what looks for all the world like an artificially maintained clearing, the utter barrenness of which is thrown into sharp relief by the masses of vines that overgrow virtually every square inch of the structure itself. Just about when a sharp observer might start to wonder who would want to spend their time defending the lifeless, hard-packed soil of the clearing against the jungle’s encroachments and why, three armed Maya ride up on horseback and begin shouting imperatively at the travelers. Unfortunately, they’re shouting in their own language, which none of the outsiders understand, and not even the leader of the horsemen (Men in Black’s Sergio Calderon) appears to speak any English or Spanish. The mystifying standoff turns ugly a moment later, when Amy (who had been photographing everything in sight since she first laid eyes on the pyramid) turns her camera on the Indios, and takes a few steps back to get them all in the frame. The instant her foot touches the pyramid, the Maya draw back their bows and take aim at the horrified girl. The leader, meanwhile, draws a pistol which he holds at the ready, although he doesn’t actually point it at anyone initially. That comes only after Dimitri steps forward in a manner rather more assertive than seems wise when people are waving guns and bows about. When Dimitri continues to advance even then, one of the bowmen skewers him with an arrow and the head Maya puts a bullet right though his nose. Jeff and the others take flight at that, in the only direction credibly open to them— straight up the side of the pyramid.

The view from the top is, if anything, even less encouraging than that from ground level. The archeologists’ campsite looks abandoned, and Mathias soon finds Heinrich’s body concealed by a tangle of vines. Those vines, incidentally, must grow awfully fast, because they’re wound all around Heinrich, even though he can’t have been dead more than 24 hours. Their sap is apparently toxic, too, because Mathias has a rash spring up all over his hands when he attempts to tear the tendrils away from his brother’s corpse. The Maya, meanwhile, are now gathering in strength around the clearing, evidently planning on camping out to prevent the outsiders from escaping the pyramid. None of the Americans’ cell phones can get a signal, and one of the Maya took Mathias’s global-range phone away from him during the scramble that followed the shooting of Dimitri. The trapped travelers have no meaningful provisions on them, and ransacking the archeologists’ tents doesn’t turn up much more in the way of food or water. The other Greeks are supposed to be following behind Dimitri, of course, but who knows when they’ll become sufficiently disenchanted with banging American college girls to feel like checking out some mangy old ruins that aren’t nearly as old as the ones they have back home, anyway? Even the one ray of genuine hope has a fecal lining, for although a cell phone incongruously starts ringing down at the bottom of the excavation shaft in the middle of the pyramid roof, Mathias falls and severely injures his spine in the attempt to go down and retrieve it. In the final assessment, though, the greatest threat facing the five youths cornered atop the pyramid is not thirst, hunger, exposure, crippling spinal wounds, or even the encamped Maya around the edge of the clearing. Rather, the greatest threat is those vines growing all over the ruins. They’re carnivorous, infectious, semi-sentient, partially motile, and even possessed of a certain mindless cunning. The Maya, or so it would appear, have dedicated themselves to keeping the pestilent plants contained, and unfortunately for Jeff and the others, that means containing anybody who comes into contact with them, too.

For seven centuries, the Maya had one of the most advanced civilizations in the Americas, despite the fact that they never really mastered the practical use of metal. They were world-class architects, engineers, mathematicians, and astronomers, and empire-builders on par with any of the great city-state cultures of the ancient Middle East. They practiced intensive agriculture on a scale and with a sophistication to match any Old World river-valley civilization, and their road system rivaled that of Rome when you take into account the degree of maintenance required to prevent the swamps and jungles of Central America from reclaiming it. Theirs is one of the oldest and most fully developed known writing systems in Mesoamerica, and the Mayan religion, so far as can be discerned from such sources as have been deciphered, was as elaborate and institutionalized as any to be found in Europe or Asia. And yet for some unknown reason, the people who had created this rich and ramified culture abandoned their cities and the lifestyle that went with them between roughly 800 and 900 AD. Scott Smith never directly raises the point, either here or in the novel, but one of my favorite things about The Ruins is how it sort of sneaks a solution to that mystery in through the back door. In fact, one of the ways in which the film improves upon the book is by putting a tad more emphasis on the implication that the Maya were driven out of their cities by the vine. It’s still shoulder-tap subtle, but by making the ruins a stone step-pyramid instead of just an earthen mound of the sort that the Olmecs used as foundations for their settlements, Smith has strengthened the unspoken back-story, even if the change was meant only as a sop to the literalism of viewers who might demand more from a ruin than some overgrown earthworks.

The other major improvement concerns the nature of the malignant vines. The vines in the novel are much more conspicuously strange than those in the movie (which look like a cross between pumpkin vines and opium poppies), and they’re a great deal more intelligent, too. In the print version, the vines are primate-smart— maybe even human-smart— and although that does offer some entertaining possibilities that the movie foregoes, it also somewhat impairs the book’s credibility. Pitcher plants and Venus flytraps already have senses of a sort and some capacity for autonomous movement; it’s a fairly short leap from there to imagine an earthly carnivorous plant evolving something analogous to animal instincts, but a much longer one to imagine such a plant developing an intelligence sufficient for both conscious planning and deliberate cruelty. But more importantly, the dumber vines in the celluloid version of The Ruins are just scarier. An organism that mocks its prey and takes pleasure in its victims’ suffering is something that a person can understand and relate to on some level, even if there’s no real chance of reasoning or even communicating with it. One that exhibits purposeful behavior without the capacity for thought, on the other hand, is irreducibly alien to human mental experience. There’s a potent air of the uncanny to these weeds that can outsmart an unprepared human despite having neither brain nor consciousness, just as there is to the magnificently complex and durable societies that ants and termites create without any trace of individual sapience. In a sense, Smith reversed himself in between writing the book and writing the screenplay. He initially made the vines weird by diverging from nature, but in adapting The Ruins for film, he stuck closer to the weirdness of nature itself. I find the latter approach far more effective in the context of this story.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact