Queen of Atlantis / A Woman of Atlantis / Lost Atlantis / Atlantis / Missing Husbands / L’Atlantide (1921/1922) ***

Queen of Atlantis / A Woman of Atlantis / Lost Atlantis / Atlantis / Missing Husbands / L’Atlantide (1921/1922) ***

People have been arguing for more than a century over whether or not Pierre Benoit was ripping off H. Rider Haggard when he wrote his second novel, L’Atlantide, even if his accusers haven’t always agreed on which of Haggard’s books he was supposed to have copied. Although She is naturally the obvious candidate, there’s also a faction that favors a later lost race tale, The Yellow God, as Benoit’s true model. Before I go any further, I should clarify that I’ve not had the chance to read L’Atlantide myself. Although an English-language translation was serialized in Adventure in 1920, under the title Atlantida, Benoit’s book did not become one of the perennially reprinted classics of pulp adventure literature on this side of the Atlantic, and I’ve never seen a copy in person. Nevertheless, I feel halfway confident staking out a position on the “no plagiarism” side of the debate, even sight unseen. That’s because there was absolutely no shortage of lost world and lost race fiction in circulation by 1919, but the only one of Haggard’s works specifically to be available in French translation at the time was King Solomon’s Mines— which nobody has charged Benoit with cribbing from. Benoit couldn’t read English, so that fact alone seems dispositive to me, notwithstanding seemingly incriminating commonalities like a sexually irresistible goddess-queen ruling over a secret Hellenistic civilization in a corner of Africa unmapped by white explorers. Besides, Benoit had exactly the same credentials as Haggard for making that shit up himself, having lived in North Africa for fifteen years, including a period of enlistment in the French colonial forces in Algieria.

Still, Atlantida and She have plenty in common even beyond their suggestively similar antiheroines, and that includes one thing that neither Haggard nor Benoit had much control over: both books have been filmed a lot. My regular readers will already have some idea how many versions of She they have to choose from, but Atlantida’s tally is fully competitive. It was adapted to the screen in nearly every decade of the 20th century from the 1920’s on, and borrowed from liberally by movies ranging from Toto the Sheik to Hercules and the Captive Women. There was even a Hollywood version in 1949, during the long, slow-simmering vogue for Orientalist fantasy and adventure films touched off by The Thief of Bagdad, but the overwhelming majority of the pictures in question originated in Continental Europe. Jacques Freyer’s Queen of Atlantis was the first of the bunch, appearing just two years after the source novel. It’s a difficult, frequently trying movie, vastly too long, hopelessly addicted to meandering, and marred by a catastrophic casting error, but it’s also a visual triumph throughout, and it consistently rallied every time it was on the verge of losing me.

The plot is impossibly convoluted, all the more so for being constructed as a bento box of nested flashbacks. Even more than usual, I’m going to have to stick to just the net vector here, or this piece will never get written. When you break it down, there are really three stories in Queen of Atlantis, each concerning an expedition by officers of the French colonial army into the Hoggar Mountains, a then-unmapped range in the far south of Algeria. The first, led by Captain Massard (Andre Roanne), forms the core of the back-story. It was intercepted at the Wells of Gamara by Tuareg raiders loyal to the chieftain Cegheir ben Cheikh (Abd-el-Kader ben Ali), and slaughtered nearly to a man. The only survivors were a Berber guide named Bou-Djema (Mohamed ben Noui) and Massard himself— although the latter was taken prisoner by ben Cheikh’s men, and never seen again. The second was a much smaller undertaking, involving only Captain Morhange (Jean Angelo, who would revisit the role a decade later, in the Francophone and Anglophone iterations of G.W. Pabst’s tripartite talkie remake), Lieutenant Saint-Avit (Georges Melchior, from Louis Feuillade’s Fantomas cycle), and the same Bou-Djema who escaped the massacre at Gamara. It too came to grief, but how exactly remains a mystery even after Saint-Avit is found, raving mad and half-dead with dehydration, by a routine cavalry patrol out of Timbuktu under the command of Captain Aynard (The Mystery of the Louvre’s Genica Missirio). The third voyage into the Hoggar Mountains hasn’t happened yet. It’s the one that a nominally recovered Saint-Avit intends to make— all by his lonesome— now that his commission has been reinstated, full in the knowledge that he will never return this time. The flashbacks that accompany Saint-Avit’s explanation of his motives to his friend and former academy classmate, Lieutenant Olivier Ferriers (Rene Lorsay), comprise the bulk of the film.

The trouble for Saint-Avit and Morhange began with the latter’s discovery of a strange inscription among the rocks near one of their early campsites. The script was one that Morhange recognized as an exceedingly ancient form of Greek, which aroused his scholarly curiosity. No surviving historical record or previous archaeological discovery would suggest that the influence of Greece had ever spread so far to the southwest, so clearly this was a find of some importance. It happened that the writing came to light shortly after Saint-Avit had rescued a Tuareg traveler from death by thirst, and the latter man informed Morhange that he knew of a cave not too far away with many such inscriptions. What neither Frenchman realized was that the Tuareg was none other than Cegheir ben Cheikh, and that he was leading them into a trap. (Bou-Djema did recognize ben Cheikh, but the wily bastard contrived to poison him before he could drop the dime about the traveler’s true identity.) Ben Cheikh built a bonfire of wild cannabis at the mouth of the cave as soon as both officers were safely inside it, effectively gassing them into a stupor.

Saint-Avit and Morhange awoke in Atlantis— no, really! As the royal archivist there (Paul Franceschi) explained, 9000 years ago, the Mediterranean Sea expanded to submerge what is now the western Sahara, all but drowning what was then the world’s most advanced civilization; the refugees became the founders of ancient Greece. Unbeknownst to the rest of the world, however, the highest point of Atlantean territory— the Hoggar Mountains— remained above the waves, and an isolated remnant of the once-great culture has survived ever since in a city of catacombs carved into the living rock of the mountains, surrounding a lush, cliff-ringed oasis. Furthermore, once the land rose up again in subsequent millennia, the Atlanteans’ isolation became strictly a one-way affair. Although it has suited the ruling dynasty to keep their domain a secret from outsiders in general, they have long employed the Tuareg to be their eyes and ears in the world. The palace archive holds books in the languages of every literate culture ever contacted by the nomads, ranging from works predating the burning of the Library of Alexandria to the latest products of Europe’s modern commercial publishing industry. Indeed, the current queen, Antinea (Stacia Napierkowska, from Satan’s Rival and the 1911 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame), and the ladies of her court have a real thing for French fashion magazines, although their tastes don’t seem to have exerted much influence on how today’s Atlanteans actually dress. Antinea’s yen for things modern and Western has, however, affected her sex life, which was ultimately what put Morhange and Saint-Avit into their predicament at her hands. She’d had 53 lovers to date, all of them outlanders procured for her by Cegheir ben Cheikh, and as fate had it, she had just grown bored with her latest one— the aforementioned Captain Massard— when the Tuareg encountered the two Frenchmen.

Although Antinea is by no means a one-man woman, she has always limited herself to one man at a time. The simultaneous arrival of two foreign males thus gave her a decision to make, which would obviously require meeting both candidates. That dual audience ultimately brought about the immiseration of five people, the monarch herself included. You see, such are the beauty and majesty of Queen Antinea that no ordinary man can so much as lay eyes upon her without falling instantly in undying love. Poor Massard was so smitten with her that he hurled himself out the window of his excavated apartment as soon as he learned that Antinea had summoned the new guys to her quarters! Saint-Avit, for his part, was not much less distraught when the queen chose Morhange over him, even though the only thing on his mind just five minutes before had been to get the hell out of Atlantis. But Morhange, it turned out, wasn’t an ordinary man at all, for he was already in undying love. He had been married once, and his wife’s premature death three years or so earlier had driven him to the extremity of joining a monastery. Morhange’s abbot released him from his vows to return to the colonial service, but not even Antinea could compete with the dead woman’s memory. This was a novel situation for the queen of Atlantis, to be snubbed every bit as thoroughly as the 53 men she’d previously provoked to suicide, and it sent her absolutely batty. Meanwhile, one of Antinea’s slave girls, the whitest supposed Mandingo you’ll ever see in your life, by the name of Tanit-Zerga (Marie-Louise Iribe), fell in love with Saint-Avit, who of course could not be bothered to look her way twice. The fact that Aynard would later find the lieutenant alone and insane should convey some sense of how bad an ending these two overlapping triangles came to for all concerned. Even now, though, Saint-Avit is not free of Antinea. That’s why he’s fixing to return to the Hoggar Mountains in the morning. And incredibly, once Ferriers has heard his old friend’s story, he knows at once that he has no choice but to go along with him.

I was still on the fence about Queen of Atlantis up until that astonishing denouement, which almost has to be the Frenchest thing I’ve ever seen in my life. I haven’t done it anything like justice, either, merely by stating Morhange and Ferriers’s intended course of action. You need to take in the whole gestalt of the thing— how the cinematography and the music and the phrasing of the intertitles combine to wax positively wistful as two guys who have learned not a damn thing ride off together into the Sahara, knowingly following their dicks to their own certain doom. It’s the knowing that’s the key here, both the characters’ knowing and Jacques Freyer’s. I’ve seen plenty of movies whose ostensibly happy or at least upbeat endings turn dark and horrid when you follow them through to their logical conclusions, and plenty of others whose ironic endings hinge on the protagonists failing to grasp how fucked they are, but this is neither of those things. Freyer has instead given us two men who deliberately embrace their fuckedness— not as martyrdom, but as the promise of a terrible ecstasy that Clive Barker’s Cenobites might appreciate— and his attitude toward their looming fate reads as a complicated form of envy. He invites us, in those final moments, to long to be as fucked as Saint-Avit and Ferriers, and to all outward appearances that invitation is extended sincerely.

Of course, that ending is but the ultimate example of a pattern that plays out repeatedly throughout Queen of Atlantis’s two hours and 46 minutes. (Incidentally, even that epic running time apparently represents the permanent loss of some half an hour of original footage!) Again and again, the film seems to be losing its way inside its maze of subplots, sub-subplots, and flashbacks within flashbacks, only to turn around suddenly and do something awesome. Maybe that means an especially striking visual effect, like the double-exposure vision of a military caravan that fades into existence on a previously empty expanse of desert as Bou-Djema recounts the tale of the doomed Massard expedition. Or it might mean a shocking turn of events, like Massard’s lurid suicide, depicted as explicitly as the limited technology of 1921 would allow. Sometimes it’s a matter of leaning into the most fantastical parts of the premise, as when Antinea shows off her shrine to all her former lovers, their bodies anodized in orichalcum according to an ancient Atlantean process long forgotten outside the walls of the valley. Other times it’s an unexpectedly sophisticated character moment, such as Cegheir ben Cheik’s reaction to discovering Tanit-Zerga’s plot to escape from Atlantis with Saint-Avit. It might mean a gag of sorts, like the festive mood that sweeps over Antinea’s court when a Tuareg caravan arrives bearing sack after sack of European newspapers and magazines. It might even mean something as simple as somebody playing with Antinea’s pet caracal as if he were nothing more than an unusually large and powerful housecat. The point is, there’s always something— some worthwhile reward for putting up with another diffuse and directionless digression to draw you back in for the next one.

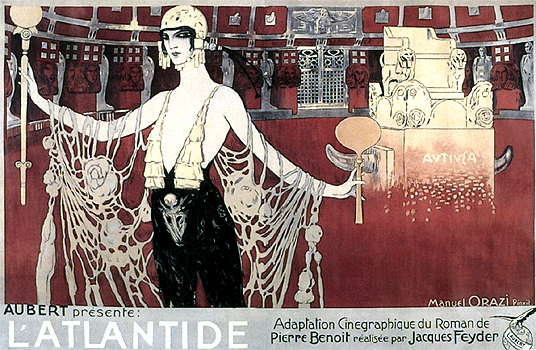

Besides, even when it’s rambling like a nursing home patient trying to tell you about life during The War, Queen of Atlantis is an exceptionally attractive film. This was supposedly the first feature-length motion picture ever shot in Algeria, and one certainly can’t accuse Freyer of failing to take full visual advantage of his surroundings. The interiors are just as impressive as the forbidding desert landscapes, too. Even they were shot in Algeria, in a massive tent of the sort in which a nomadic chieftain like Cegheir ben Cheikh himself might make his home, dressed with intricately painted flats executed by the renowned art nouveau illustrator Manuel Orazi. Orazi may also have designed the intertitles, although I’m by no means certain of that. At the very least, many of them are works of art in themselves, esthetically in keeping with the action they elucidate.

There is one problem that nothing else in Queen of Atlantis can quite overcome, and unfortunately that’s the Queen of Atlantis herself. Stacia Napierkowska had been one of Pathé’s biggest stars a decade earlier, so it’s understandable that she’d be considered a catch for the leading female role in one of the grandest products yet of the French film industry. But in Napierkowska’s early-1910’s heyday, closeups weren’t really a thing yet, and it therefore didn’t matter what sort of face was perched atop her lithe ballerina’s body. In 1921, However, Freyer was using closeups galore, and they don’t do his leading lady even the slightest little favor. I don’t think it’s unfair to ask that an actress playing the sexiest woman alive be, at a minimum, halfway cute. But perversely, the closest the irresistible, unforgettable, rapture-inspiring ruler of Atlantis ever comes to being really attractive is toward the end of Saint-Avit’s long flashback, when Antinea is psychotic with jealousy, and Napierkowska is made up to look like she’s been living in a dumpster for a month and a half. “Hot for a crack-smoking gutter punk” is definitely a look that I can get behind, but I don’t think it’s the one that this part really calls for.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact