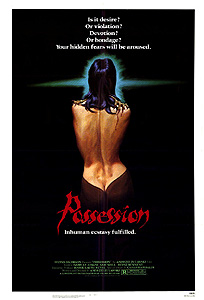

Possession (1981) **

Possession (1981) **

With Possession, writer/director Andrzej Zulawski attempts to wed the art house to the grindhouse; unfortunately for the audience, the resulting marriage works out about as well as the one between the movie’s two central characters. There are a number of good ideas struggling to break free of the quagmire that is Possession, and when one or another of them briefly gets its head up above the muck, the film really does work. There aren’t nearly enough of those moments, however, and the self-indulgent, self-congratulatory manner in which Zulawski handles just about everything that goes on between one set of credits and the other makes for about as thoroughgoing a case of self-sabotage as you’re ever likely to see.

Mark (Sam Neill, of Omen III: The Final Conflict and In the Mouth of Madness)— evidently some sort of spy— returns to his West Berlin home after a long assignment abroad to find his family life an utter shambles. Right off the bat, he realizes that he and his wife, Anna (Isabelle Adjani, from The Tennant and Nosferatu the Vampyre), have nothing to say to each other. Then their attempts to have sex that night fail miserably, and Mark begins to believe that Anna has taken a lover in his absence. She denies doing any such thing and Mark drops the subject, but in a way that suggests he doesn’t entirely believe her. He’s right not to. The following evening, when Mark comes back from a debriefing session with his superiors, there is no sign of Anna in their apartment, nor of their son, Bob (Michael Hogben), either. Eventually, Mark thinks to have a close look around the place, and he uncovers a good bit of circumstantially incriminating evidence— shelves upon shelves of books on subjects in which his wife had never previously exhibited an interest, for example. Then he hits the jackpot. In a drawer in Anna’s desk is a postcard from India from a man named Heinrich, the message on which could scarcely be any plainer: “Here I have seen half the face of God. The other half I see when I look at you.” Over the next several days, Mark wends his way through a labyrinth of lies and alibis until he finally manages to corner his wife into admitting to the affair. The explanations she offers are strange, however. Granted, one hardly expects true rationality from such things, but what Anna tells him about how she found herself in Heinrich’s bed seems almost actively crazy. That, in fact, is part of what leads Mark to reconsider his original decision to cut his ties completely, and leave her to care for Bob with no involvement from him beyond a monthly child support check.

The second part is what Mark discovers once he puts himself together again following the three-day nervous breakdown that began the moment he and his wife parted company after their big talk. It was Anna’s friend, Margi (Margit Carstensen), who found him and got him back to normal, even though Mark and Margi have always passionately loathed one another. Having learned that he has spent three days he doesn’t even remember over at her place, Mark gets himself together and heads home. There, he finds that Anna, far from following through on her stated intention of becoming Bob’s sole caregiver, has actually left the boy alone in the apartment the entire time that he was with Margi. What’s more, she then has the nerve to call Mark from her lover’s place, and pretend that she was the one who was staying with her old friend! And soon thereafter, her mysterious lover calls, too, and threateningly informs his hapless rival that Anna will be staying with him from now on. That, as you might imagine, is where Mark draws the line.

With a resourcefulness that well befits his occupation, Mark tracks down the address of the enigmatic Heinrich (Nea: A New Woman’s Heinz Bennet). He proves to be the biggest flake this side of San Francisco Bay, but his effete appearance is misleading; when Mark gets physical with him, Heinrich pulls out some weird Asian martial arts move and lays him on the floor without breaking a sweat. The important thing, though, is that Anna is nowhere in Heinrich’s apartment, and both he and his elderly mother (Johanna Hofer) claim not to have seen her in some weeks.

Utterly perplexed at this point— both by Heinrich’s claims not to have seen Anna and by the woman’s own disconcerting habit of popping into her erstwhile home to act as if nothing were amiss, only to turn savagely on Mark the moment he tries to strike up a conversation with her— our hero hires a private detective (Carl Duering, from The Electronic Monster and The Boys from Brazil) to follow his wife the next time she makes one of her unscheduled appearances. Mark wants to know what she’s really doing with her days. What the detective uncovers solves a great many mysteries, but raises nearly as many of its own. Anna, it turns out, isn’t only cheating on Mark. She’s cheating on Heinrich as well, and she’s doing it in a seemingly uninhabitable apartment clear on the other side of the city. There’s something else, too, although the detective doesn’t live to pass this information on either to Mark or to his bosses at the agency— Anna’s other lover isn’t human, and she’s ready, willing, and able to kill anybody who gets wise to her outrageous secret.

When Zulawski was trying to get funding for Possession, he told prospective backers that he was looking to make a movie about “a woman who fucks around with an octopus.” That by itself should have made Possession a film not to be missed, especially when you consider that Zulawski (like David Cronenberg making The Brood) was mining the ugly collapse of his own marriage for material! Add to that the casting of an authentic wacko like Isabelle Adjani in the role of the octopus-fucker, and the employment of an effects maestro like Carlo Rambaldi to build the octopus being fucked, and the failure of this movie to come together becomes even more bewildering. But remember what we’re dealing with here. Zulawski is a member in good standing of the European Art-Film Directors’ Navel-Gazing Society, and over the course of Possession’s two hours and change, he exhibits practically every one of the behaviors for which art-film directors are typically mocked. Indeed, by the time it was all over, I had developed the distinct impression that Zulawski really had far more in common with Heinrich than he did with Mark, his obvious stand-in among the movie’s dramatis personae. Nearly every moment of high emotion is announced by the camera swirling tightly around the scene’s central player while they lose themselves in exaggerated histrionics. One especially risible scene of this type consists of hardly anything more than Adjani rapidly rotating in what appears to be a subway corridor and screaming inarticulately at maximum volume for literally minutes on end. Meanwhile, even when the actors are given genuine lines to deliver, what they are called upon to say bears not the slightest resemblance to real human speech. The numerous scenes in which Heinrich prattles endlessly about God, or in which Mark prattles equally endlessly about dogs crawling under porches to die, could all serve as examples, but even more impressive in its unimpressiveness is the one that has Anna struggling to recount some fable or other about “the sisters of Chance and Faith;” she just ends up talking herself into one corner after another, stopping and starting, never getting any closer to whatever her point is. Honestly, it looks like Adjani was having trouble remembering what she was supposed to say, but Zulawski just kept the cameras rolling on anyway! What makes all this foolishness so infuriating is that about every fifteen minutes, all the elements will fit themselves together in just the right way, and for about 30 seconds, we’ll get a glimpse of the movie Possession ought to have been.

In light of what’s most wrong with this film, I rather think I outsmarted myself in watching the version I did. You see, when Possession originally played in the US, its distributors understandably concluded that it was a movie with no natural audience in this country, and that some serious editing would be necessary if they were going to turn a profit on it. Either it could play the art house circuit with its grislier exploitation elements removed, or it could lose all the psychobabble and play 42nd Street instead. By the time the American editors put their scissors away, Possession’s running time had contracted to a mere 80 minutes! Naturally, the general consensus has been that this was sheer vandalism, and that Zulawski’s vision had been inexcusably compromised. As is my usual practice when I hear about such things, I held out for an uncut print, and I never did see the old US edit. Now, however, I’m thinking maybe that was a mistake. Since Zulawski proved perfectly capable of “compromising his vision” all by himself (unless, of course, he deliberately set out to make two hours’ worth of an incoherent and often ludicrous mess— which I suppose I shouldn’t put past him), and since most of what drags Possession down is exactly the sort of thing an American distributor would be likely to cut out, maybe I ought to give the 80-minute version a try.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact