The Magic Christmas Tree (1964) -**½

The Magic Christmas Tree (1964) -**½

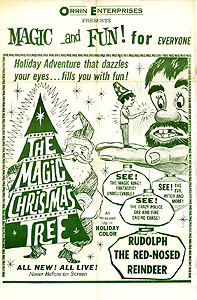

Watching The Magic Christmas Tree solidified an idea that had been taking shape in my head for a while: children’s entertainment in the 1960’s was already as weird as everybody else’s would become in the 1970’s. I have no idea why that should be, but the premise itself seems close to irrefutable. Just look at this obscure matinee quickie for a really extreme example. Along the way to imparting a moral lesson about selfishness and greed, The Magic Christmas Tree serves up a stereotypical witch; the titular bitchy coniferous genie; a boy temporarily transforming himself into a petty and incompetent trickster god; an uncommonly befuddled and senile-seeming Santa Claus; a pocket universe ruled by a seven-foot, child-enslaving muscle bear; and the most inadvertently dystopian portrayal of mid-century suburbia that I’ve seen in many a year. All those things come packaged with production values suggestive of some impoverished UHF television station’s in-house holiday special. The filming locations, for example, are scattered about La Verne, California, rather than Los Angeles, and the township’s historic 1927 Seagreaves fire engine puts in a prominent appearance, as if the local chamber of commerce had contributed a substantial share of the funding. A monster-suit regular from “Lost in Space” is the only actor in the cast with anything else on his resumé. And with a running time of only 57 minutes, it might just barely have been squeezed into a mid-60’s television hour if the station broadcasting it had extremely low operating overhead. Yet The Magic Christmas Tree did not arise from that environment at all. Whatever TV afterlife it may have gone on to, this movie was certainly shown in theaters first, and if the diversity of advertising material I’ve found on the internet is any indication, it must have enjoyed a fairly wide release— possibly including multiple reissues. I have no idea how such a thing is possible for what appears to have been a vanity project by director Dick Parish, beyond to observe that Hal Warren somehow got Manos: The Hands of Fate into theaters, too.

We begin with three young boys eating lunch at school. As seems always to be the case in films from this era, none of the kids are happy with what their mothers have packed for them, and the ringing of the lunch bell provokes widespread haggling over who’s going to trade what to whom. Mark (Chris Kroesen), the most overbearing and prickish of the three, drives an especially hard bargain. In retrospect, we’ll realize that this is supposed to establish him as more than usually devoted to getting stuff— and to getting it on exactly his own terms— but right now it just looks like random jackassery. We also learn that today is Halloween (yeah, that took me by surprise, too), and that Mark is plotting mischief. Like most small towns of sufficient age, La Verne has a rickety old house that’s supposed to be haunted. And as if that weren’t enough, the old lady who lives there, Miss Finch (Valerie Hobbs), is supposed to be a witch. Mark’s idea for big Halloween excitement is to sneak into the Finch place, and… I don’t know. Get caught? Get grounded? Get arrested for breaking and entering? I’m not sure Mark has really thought this through, even leaving aside the issue of ghosts and witches. His friends have ready-made excuses for not joining in his hare-brained enterprise (one has to babysit, while the other is going to a party), but Mark is an adept manipulator for his age. He manages to brow-beat the other two kids into following him as far as Miss Finch’s property line on the way home from school.

The old lady is actually out in the yard when the boys arrive, which cures Mark’s friends of any desire they might have had to accompany him any further. Her business is innocent enough, though. It seems her pet— a black cat named Lucifer, naturally— has treed himself, and is unable or unwilling to climb down. Even so, Miss Finch’s cat-rescuing efforts lead her into direct confrontation with Mark, whom she seizes by the arm the instant she notices him skulking around on her land. Miss Finch sort of half sweet-talks and half threatens him into scaling the tree to get Lucifer down, but he’s not as skillful as either he or the supposed witch imagines. Lucifer’s non-cooperation causes Mark to lose his grip on the trunk, and the next thing the boy knows, he’s landing head-first on the ground below.

When Mark regains consciousness, the film stock has changed from black and white to color, Miss Finch’s house looks completely different, and the old lady herself is sporting a pointy hat to match her black dress and black cat. (We can also see more clearly now how lousy Valerie Hobbs’s age makeup is, but that’s not something Mark would pick up on.) Obviously that means Mark is dreaming, and we can expect him to awaken for real in his familiar monochrome world at the end of the film, probably having learned some utter no-brainer of a lesson. In the meantime, though, we’ll pretend to go along with everything. Miss Finch reveals that she really is a witch after all, and as Mark’s reward for saving her familiar, she gives him a magic ring bearing an extremely crude image of Santa Claus. The ring contains a magic seed which will grow, if planted under the wishbone of a Thanksgiving turkey, into a magic, wish-granting tree. All Mark has to do is to remember a simple yet nonsensical incantation, and he’ll get three wishes.

Fast-forward to Thanksgiving. After dinner, Mark takes the wishbone out into the backyard to plant it with the seed from the witch’s ring. Overnight, the tree— which turns out to be a fir of some kind— grows to a height of some seven feet. Mark’s father (probably Dick Parish himself, to judge from his position in the cast credits) discovers it while mowing the lawn the following morning, when he crashes the gas mower into it. We’re asked to believe that this is because Dad wasn’t expecting to find a tree there, but given the size of the thing, that makes sense only if he habitually mows the lawn with his eyes shut. Consequently, it’s hard not to side with Mom (Darlene Lohnes) when the lawnmower’s cacophonous death-throes draw her out to the yard to see what her idiot husband is up to. Dad isn’t the sort to let a tree make a fool of him without a fight, even if he can’t explain what it’s doing on the property in the first place, and he determines to cut down the interloping evergreen. Naturally that leads only to his even greater humiliation, as the tree’s enchantment makes it impervious to saws and axes. In the end, Mark’s father has no choice but to accept the strange new addition to the landscaping.

Now we jump ahead to Christmas Eve. At this point, we see that Mark’s parents are equally matched in their thick-headedness, for not only has Dad neglected to buy a Christmas tree, but Mom has failed to notice the absence of a big honking pine from the living room until now. While the rest of the family rushes out to correct that oversight, Mark stays home to see about those wishes he’s owed. The tree demonstrates further the reality of its magical powers first by talking to Mark (it sounds like a very excitable and easily annoyed homosexual), and then by teleporting itself into the house and festooning itself with decorations. That last turns out to be a stroke of good luck, for Mom and Dad will be coming home predictably empty-handed from their tree-shopping excursion. By the time that happens, though, Mark has already used his first wish, which is to be all-powerful for an hour. It’s a good thing Mark tends to think small, because what he does with that godlike might is to create spiteful havoc all over town. He turns night into day, induces his neighbors to engage each other in Stoogian pie-fights, and brings every emergency rescue vehicle in La Verne to mischievous life. (I’m left with the impression that this whole sequence was written as an excuse to trot out the antique fire engine, because it and its crew get the lion’s share of the attention for the duration of Mark’s career as an omnipotent nuisance.)

Wish #2 comes late that night, after the rest of the family is asleep, and while it’s just as petty as the first wish, it’s more grandiosely petty, if that makes any sense. Mark wants Santa Claus all to himself this year, so as to monopolize all the world’s new toys the next morning. The tree tries to talk him out of being such an appalling little asshole, but it’s no use. Mark knows what he wants, and what he wants is mastery over Santa Claus. Needless to say, that doesn’t turn out quite the way he expected. First of all, the failure of Santa Claus to appear at any house but Mark’s (where he is unable to leave the living room) causes nationwide, and perhaps worldwide, panic. Police forces everywhere are called out to search. Air Force fighters begin patrolling Santa’s usual route from the North Pole. Strategic Air Command goes on full alert, presumably with orders to nuke the perpetrators in the event that Santa Claus has been abducted. Then of course there are all the children who wake to discover not a single present in their stockings or under their trees. And you know what? After all that, kidnapping Santa doesn’t even gain Mark anything! Everyone knows that Santa Claus brings gifts only to the good kids, and this is about as bad a deed as Mark is capable of committing. Naturally Santa doesn’t bring a single present with him when he takes up his captivity in Mark’s living room, so Mark has gone and ruined Christmas for himself along with ruining it for everybody else. That’s not all, though. So great has Mark’s selfishness been that it transports him into another dimension, where the ogre Greed (Robert Maffei, from Atlantis, the Lost Continent and those “Lost in Space” episodes I mentioned earlier) is ecstatically happy to see him. Greed is always on the lookout for new human slaves, and he likes to get them young whenever possible. If you’re thinking the only way out of Mark’s predicament is to use his third wish to undo his second, then you must have seen or read… well, pretty much any wish-centric cautionary tale since “The Monkey’s Paw” would do the trick.

There isn’t much to be said about The Magic Christmas Tree from a technical perspective, beyond that it’s very cheap and very shoddy. Fortunately, there’s something much more interesting about this movie than technique or lack of same. Consider for a moment the overall tenor of American pop culture in the early 1960’s. This was the part of the decade that didn’t fully realize it was no longer the 1950’s. History was setting the stage for the convulsions to come, but it would have taken a perceptive observer indeed to predict just how wrenching those convulsions would be. If we suppose that popular culture offers us clues to how societies see themselves, then the impression conveyed by American entertainment in the early 60’s is mostly one of vast, almost smug complacency. Life is good, the era’s mass media seem to say, and it’s only getting better. Institutions are portrayed as trusted and trustworthy. Even the Cold War paranoia that loomed so large in the background of the previous decade’s movies, television, and literature visibly recedes, and why not? Sputnik notwithstanding, the outcome of nearly every confrontation between the Superpowers to date tended to suggest that maybe those Commies weren’t so tough after all.

Superficially, The Magic Christmas Tree looks like a part of that pattern. All of its characters are comfortably middle-class in a modest, small-town way. La Verne is clean, picturesque, and economically vital. Miss Finch is the only person in town who seems to have hit upon the idea of conscious nonconformism, and even she (as an old spinster embracing her virtually inevitable reputation as a witch) is rebelling in a thoroughly conventional way. So it’s Mayberry in color (or at least mostly in color), right? Well, maybe. But get a load of Mark’s parents. Even coming after ten years’ worth of incompetent, nitwit sitcom dads, Mark’s father is an impressively incompetent nitwit— almost like a less screamy version of today’s insufferable movie man-children. And what a piece of work Mom is! She spends more time and effort mothering Dad than she does mothering Mark and his sister (Did I forget to mention that Mark has a sister? It’s just as well— she never actually does anything…), but her attentions toward everyone are almost totally negative. When she isn’t nagging or belittling, she ignores her family completely. And Darlene Lohnes’s idiosyncratic species of bad acting makes her seem like she’s pilled up more or less constantly. There’s no sense that the boy’s elders derive any satisfaction from anything in their lives, and it kind of stands to reason that they’d bring Mark up to be the particular form of little monster that he is. There’s something else that makes this suburban hellhole even more curious, too. When Mark has his bump on the head, and everything around him changes, Miss Finch informs him that all the new input is because he’s seeing truly for the first time in his life. Yet we also know that The Magic Christmas Tree is doing the Wizard of Oz thing, and that everything in the color portion of the film is just a dream Mark has while he’s unconscious. It’s a weird confluence of ideas, and it’s made all the weirder by the fact that only in the dreaming-but-seeing-truly phase are we ever shown anything of Mark’s home life, or of the town where he lives. The implication— surely accidental— is thus that this grotesque parody of the Good Old Days is what Mark subconsciously believes to be the hidden truth behind his world. No wonder he fantasizes about laying it all in ruins!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact