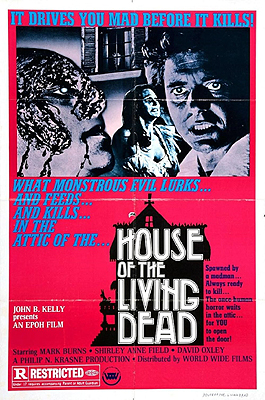

House of the Living Dead / Curse of the Dead / Skaduwees Oor Brugplaas (1973/1976) **½

House of the Living Dead / Curse of the Dead / Skaduwees Oor Brugplaas (1973/1976) **½

You will perhaps not be surprised to learn that when writers on international film history turn their attention to the development of South Africa’s movie industry, they don’t have much to say about cheap gothic horror flicks made as co-productions with an eye toward the export markets in Britain, Australia, and North America. Consequently, I’m not in a strong position to explain how or why House of the Living Dead came about, any more than I can explain why it’s called that when the closest things to the living dead that ever appear are a bunch of bottled souls stashed away in a mad scientist’s laboratory. What I can say is that the pace of South African film production, which had amounted to a mere trickle since the silent era, slowly but steadily mounted after 1956, when the dominion government instituted a subsidy system to encourage domestic moviemaking. Then in the 60’s, the newly independent Republic of South Africa began attracting significant attention from overseas, as competition from television drove established studios all over the Western world to favor actual location shooting over faking it on a soundstage. Not even the biggest TV broadcasters could afford to send crews to Africa, so setting up shop in Durban or Cape Town was a good way to enhance the impact of an exotic adventure film. Some of those outsider operations resulted in big-ticket pictures like The Cape Town Affair or The Naked Prey, but bottom-feeders like Harry Alan Towers got in on the act, too. Naturally House of the Living Dead sits somewhere toward the latter end of that spectrum. Its three producers included the local Matt Druker, the London-based Basil Rayburn, and the American Philip N. Krasne (whose work in a similar wheeler-dealer capacity we’ve seen before in Monster from Green Hell). And although this is an altogether insignificant film on the merits, extremely patient fans of mid-century gothics might get something out of it anyway, just for the novelty of its setting. They might also enjoy some of the truly weird places this movie goes once the nature of the mystery at its core starts coming into focus.

The time is the latter half of the 19th century; the place, a vineyard plantation in the Cape Colony. A guy who looks like he’s cosplaying as Orson Welles’s character in Necromancy (Mark Burns, from the other movies called Count Dracula and It!) captures a young baboon, stuffs it into a burlap sack, and limps off with it across the fields. He is observed with varying degrees of disapproval by a man on horseback (also Mark Burns, but without the absurd glue-on beard), a field hand (Bill Flynn), and an elderly lady (Margaret Inglis) peering out from her window in the huge, English-style plantation house nearby. Finally, in a laboratory stuffed to bursting with caged animals of various species and a comprehensive assortment of the specialized glassware favored by all the best mad scientists, he straps the baboon to the workbench, and performs some manner of extractive surgery on its brain. (But nothing so typical or obvious as removing the entire organ.)

It’ll be a while yet before any of this becomes clear, but the Orson Welles cosplayer is Dr. Breckinridge Brattling, known to his intimates as Breck. The virtually identical guy astride the black stallion is Breck’s twin brother, Sir Michael, who owns the plantation. The old dame in the window is the twins’ widowed mother. The field hand is Simeon. And the horse (no, really— this is important!) is Saracen, the pride of the Brattling stables. Breck, unsurprisingly, is the current black sheep of the family, what with his mysterious research that got him drummed out of some medical faculty back in the home country, but to hear his mom tell it, Brattling wool has been that color more often than not for generations. Indeed, Lady Brattling is extremely annoyed with her other son just now over his plans to import his fiancée, Mary Anne Carew (Shirley Anne Field, from House of Hookers and Horrors of the Black Museum), rather than letting the bloodline lapse like it deserves to in her estimation. And if anyone wanted to ask the nonwhite laborers who comprise the bulk of the plantation workforce (which of course no one does), they’d find Lady Brattling’s sentiments echoed wholeheartedly. Among that lot, the consensus has it that Breck is a soul-stealing warlock, and even Aia Kat (Amina Gool), the local conjure-woman, has nothing good to say about him.

On the night of what I take to be the celebration of a successful harvest, Breck demonstrates once and for all how black a sheep he really is. While everyone else’s attention is set on revelry, the doctor unlocks the stable door, then introduces a venomous snake into Saracen’s stall, provoking him to break loose. Next, after Simeon sneaks away from the party for a tryst with Annie the maid (Cold Harvest’s Lynne Maree), Breck waylays him, hauls him up to the lab, and does to him whatever he did to that baboon before. The next day, Jan the overseer (Ben Dekker, from Survivor) finds Simeon’s corpse in the vine fields, cunningly abused in such a way as to suggest that he was kicked to death by the runaway stallion. Sir Michael quickly comes to suspect fouler play, however, for his brother forgot something important while rigging the scene to frame Saracen for killing Simeon. In his haste, he failed to notice that the murdered field hand left an inconspicuous trail of blood drops on the floor, all the way from the laboratory to the front door. Michael does notice, and although he can’t be certain what the clue signifies, he’s sure it isn’t good.

Maybe none of that matters, though. When Mary Anne arrives at the nearest train station soon thereafter, she hears from a fellow passenger, Dr. Collinson (David Oxley, from The Hound of the Baskervilles and Svengali), that there’s been still another tragedy on the Brattling estate. Breck, too, has taken a kicking from the now-feral Saracen, and although he survived the initial assault, the prognosis for his recovery is not good. Collinson, who came to the Cape Colony to visit the Brattlings’ neighbor, Hugo De Groot (Limpie Basson), has a special interest in Breckinridge’s well-being, because they studied together in medical school, and Collinson found Brattling’s unorthodox ideas fascinating, if not necessarily persuasive. He was especially intrigued by Breck’s notion that the human soul must have a physical existence, from which it would follow that souls could someday be studied in much the same way as other physical yet immaterial forces like magnetism, electricity, or gravity. As Mary Anne learns upon reaching the plantation, however, there’s little prospect of Breckinridge entertaining a sickbed visit from an old friend. Lady Brattling and Sir Michael won’t even allow Mary Anne to meet her future brother-in-law in his current condition!

Still, for a sequestered invalid, Breckinridge sure does seem to get around. Rare are the nights when Mary Anne doesn’t spy from her bedroom window a black-cloaked figure galumphing about the mansion’s grounds in a distinctive, lopsided manner at an hour when everyone who isn’t up to something nefarious ought to be in bed, or hear footsteps matching that peculiar gait pacing the hallways of the upper floors. Sometimes she even hears someone playing fiercely melancholy music on the organ in the main parlor, which is said by the servants to have been a hobby of Breck’s before his accident. Meanwhile, Lena (Dia Sydow), Mary Anne’s personal maid, certainly hasn’t lost any of her old fear of her master’s brother, at least if we’re to judge by her insistence upon stocking the house with Aia Kat’s protective charms in defiance of both Sir Michael’s and Lady Brattling’s orders. And when the old hag herself is found trampled to death, Sir Michael has a veritable revolt on his hands. The workmen don’t believe for a moment that even so powerful and spirited a horse as Saracen could survive more than a few days on the veldt without human aid, so the new consensus has it that Breckinridge has somehow made an assassin of the stallion’s ghost. If there’s a witch-war being waged on the plantation, then the workers all know whose side they’re taking. Presenting Sir Michael with Aia Kat’s body, they offer him a choice: either he surrenders his abominable brother to be lynched, or the Brattlings can find themselves a new staff of laborers. Obviously Sir Michael can’t just throw Breck to the mob, whatever misgivings he harbors about what goes on in the lab upstairs, and the estate becomes a quieter, lonelier place thereafter.

You can’t have two weird deaths, an equally weird maiming, and a labor uprising, though, without attracting official attention, and Sir Michael soon finds himself playing host to Captain Turner of the Cape Colony police (Nobby Clark, from Return of the Family Man and Gor). Like the recently departed field workers, Turner is of the opinion that Sir Michael’s supposed rogue stallion is being exploited as a cover for human malfeasance, although he naturally suspects something more prosaic than a warlock commanding a ghost horse to kill for him. Michael, escalating his involvement as his brother’s accomplice after the fact, tries to forestall Turner’s investigation by saying that Breckinridge died suddenly that afternoon from the lingering effects of his injuries, but accomplishes no more than to buy time by getting the captain to begin his efforts with the grounds rather than the house itself. Then again, since Breck ambushes and kills Turner while he’s touring the vineyards, that turns out to be time enough for the moment. Alas for the Brattlings, Lena witnesses the captain’s murder, and escapes to the De Groot plantation despite Breck’s best efforts. That gets Dr. Collinson involved— not least because he took quite a liking to Mary Anne during their encounter at the train station a few weeks back. Meanwhile, Captain Turner has superiors, and it isn’t long before Colonel Pringle (Ronald France, of Nukie and Red Water) comes sniffing around to discover what became of his missing man. And Lady Brattling, for her part, is coming around to the view that she needs to be more proactive about putting an end to this family of weirdoes and maniacs that she married into all those years ago.

It’s a subtle thing, but once I noticed it, I couldn’t stop seeing it in every frame of House of the Living Dead: despite not only being set in Africa, but actually having been filmed there, this movie’s cast contains not a single black performer— not even an extra with no dialogue! To be sure, there are plenty of non-white supporting players. Dia Sydow is ethnically Indian. Amina Gool is of Malay extraction. The crowds at the harvest festival and the mob that comes for Breckinridge include Arabs and Moors and various peoples of southern Asia and the Indies. But there’s nary a native of Subsaharan Africa to be seen anywhere. That’s how committed the Apartheid regime was to racial segregation in the 70’s. Even in a cheap, junky horror film made principally for overseas consumption, there could be parts for “colored” performers (as South Africans of the era called Asian, North African, or mixed-race people), but black talent could fuck right off. The total absence of black faces from the screen gives House of the Living Dead a quality of subliminal wrongness even before you consciously notice it, which turns downright queasy once you do. Even in comparison to the most disgraceful excesses of old-timey Hollywood racism, this is some bizarre next-level shit!

How much that interferes with your appreciation of this movie’s modest merits is your business, but there is some stuff to appreciate here if you can get past it. Although the pieces of the basic setup— unprepared, virginal heroine marrying into a damned family; hostile elders; rumors of witchcraft; evil doppelganger brother lurking in the attic— are fairly routine for the subgenre, the specifics of how they’re combined here are markedly less so. It also does interesting things to the conflicted class politics implicit in most gothic fiction to layer colonialism on top, especially when the “ignorant,” “superstitious” menials turn out to be basically right about practically everything. Breckinridge Brattling is a fun villain, with a line of mad research that I’ve never seen anywhere else in quite this form before. And speaking of never seeing things before, House of the Living Dead deserves props just for positing a Cape Colony plantation supposedly haunted by the ghost of a horse— and it deserves even more for having the phantom stallion turn out to be real after a fashion, and for setting it loose to play a major role in the climax. That’s weird in ways that gothic cinema rarely has the gumption to be, even though it aligns very closely with the peculiar hauntings that were a fixture of gothic literature during its 18th-century primeval era.

Just the same, it probably does take a real antiquarian weirdo to extract that level of enjoyment from House of the Living Dead. For more casual, less nerdy fans, the slow pace and confusing narrative construction alone will make this movie tough going, and the tendency for important things to happen off camera is likely to be an out-and-out deal-breaker. Such viewers are also sure to be annoyed that all the supernatural manifestations turn out to be mostly invisible, so that the final battle between Breckinridge and his menagerie of bottled spirits devolves into Mark Burns flailing about in a frenzy with a horseshoe-tipped iron cudgel against a host of colored key lights. Honestly, I kind of admire the cheapjack audacity of that, since there was never any way for a production on this scale to make that scene look actually impressive. I harbor no illusions, though, that it’ll hold much appeal for normal people. The same even goes for the oft-belabored portrait of Saracen which rears from the landing above the mansion’s main staircase, the atmospheric power of which is severely compromised by both the flea-market quality of the brushwork and the childish conception of equine anatomy that the painting displays. So maybe you should treat those two and a half stars at the top of the page as the connoisseur’s (or sicko’s) rating; everyone else can plausibly cut it down to two, or maybe even one and a half.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact