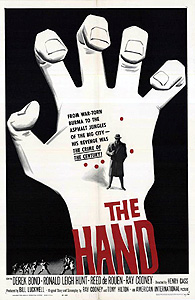

The Hand (1960) **

The Hand (1960) **

During the 1960’s, one of the biggest trends in European suspense and horror cinema was the tremendous explosion of movies based on or inspired by the writings of British mystery author Edgar Wallace. Perhaps counterintuitively, it was in Germany that the craze took root most strongly, but the English did get in on the action, even if not with as much fervor as they had back in the 30’s and 40’s. What does that have to do with The Hand, the credits to which are entirely unadorned by the names of either Wallace or his similarly prolific son, Bryan? Simple. The Hand is what you get when you want to make an Edgar Wallace movie, but don’t have the cash on hand to spring for the rights to any of his novels. Though neither of the Wallaces were involved at any level, their influence is stamped deeply into every one of this film’s 61 minutes.

The Hand begins in Burma, 1946. I must confess that this prologue confuses the hell out of me, because it depicts a regiment of the Royal Army still locked in combat with organized Japanese forces— and losing, at that— even though the Japanese signed the documents formalizing their unconditional surrender to the allies on September 2nd, 1945. In any case, the Japanese have just captured three British soldiers, and have brought them before an English-speaking officer for interrogation. Corporal George Adams (Bryan Coleman, from Blood of the Vampire) is firmly professional in his refusal to cooperate with his captors, while Private Michael Brodie (Reed Deroven) is openly defiant. The only captive who seems at all worried about what the Japanese might do to him is the lieutenant with whom the other two men had been captured (Derek Shaw, of Stranger from Venus), who thinks the safest course of action would be for the three of them to agree upon some relatively harmless piece of information to cough up in order to placate the Japanese captain. Evidently this guy hasn’t been paying attention to the stories about what goes on in Japanese POW camps. The interrogations begin before anything is settled, however, and both enlisted men continue with their personal polices of stony silence. In retaliation, the interrogator hacks off their right hands with his katana. Then he sends for the lieutenant…

Jump ahead to what was then present-day London. A policeman spies a notorious old drunk named Charlie Taplow (Harold Scott, from The Brides of Dracula) sleeping off a bender in an alley, and goes to rouse him from his stupor and move him along. But when the constable gets close enough to touch Taplow, he sees a clumsily-wrapped fresh stump where the man’s right hand ought to be, and discovers a preposterous amount of cash stuffed into the pockets of his overcoat. Taplow is understandably none too coherent in his explanation, but the gist of it seems to be that some unknown man accosted him at the pub, and offered to pay him £500 to have his hand amputated.

Now you don’t spin a yarn like that without bringing the cops swarming to you, and within perhaps an hour of Taplow’s commitment to the nearest hospital, Detective Sergeant David Pollit of Scotland Yard (No Place Like Homicide’s Ray Cooney) is on the scene looking to figure out what’s going on. When the nurse on duty says it’s okay for Taplow to have visitors, Pollit has him repeat his story in greater detail. Evidently the man who paid Taplow for the amputation called himself Roberts, and the operation was performed at a hospital somewhere outside of London proper. The detective doesn’t really believe Taplow’s tale, but he reports it nevertheless. Scotland Yard’s overall interest in the case increases considerably, however, when Taplow disappears from his hospital room and turns up dead in the Thames some time later that very night.

Pollit’s superior, Inspector Munyard (Ronald Leigh-Hunt, from Curse of Simba and Melody of Hate), takes over the case the moment it turns into a murder investigation. A search of Taplow’s personal effects uncovers a train ticket purchased on the night he was picked up, and by poking around in the vicinity of the station identified on it, Munyard and Pollit find their way to the Autumn House nursing home, where the sign-in sheet records that a man named Roberts was checked in a few days before. The doctor on duty says that Roberts had been in to have a septicemic hand amputated, and that he had checked himself out against his surgeon’s orders after only one day of convalescence. Obviously this is Taplow we’re talking about, and just as obviously the real Roberts was somehow able to leverage the surgeon who performed the operation into cutting off the hand on false pretenses. The surgeon in question was Dr. Simon Crawshaw (Garard Green, of The Flesh and the Fiends and The Crawling Eye), and it is blatantly evident that he knew something about the whole scenario wasn’t quite kosher. Crawshaw made no records of the operation, and the only person he had assisting him was Nurse Geiber (Jean Dallas), with whom he is romantically involved, and whom he can therefore presumably trust completely. And when Munyard and Pollit corner Crawshaw after he returns to Autumn House following an unexplained two-day absence, the doctor shoots himself in his office rather than tell the cops anything! The trip to Autumn House does produce a couple of profitable leads, however. For one thing, an agitated-sounding man calls the clinic on the phone while Munyard is there, asking to speak to Roberts; the inspector manages to keep him on the line long enough for the operator to trace the call. Beyond that, Dr. Crawshaw’s brother, Roger, puts in an appearance, and while neither of the detectives is in a position to notice this, we can see that he is none other than the British officer from the hand-chopping Burma prologue. There’s just no way that isn’t an extremely important connection.

As the investigation progresses, Munyard will gradually determine that somebody— probably the mysterious Roberts— blackmailed Dr. Crawshaw into amputating Charlie Taplow’s hand, and that somehow, the illegal surgery is related to an ongoing feud between Roberts and Michael Brodie, Roger Crawshaw’s old cellmate in the Japanese POW camp. Unfortunately, Brodie himself is unwilling to talk about the feud, and nobody— not even Brodie’s wife (Madeleine Burgess) or brother (Reginald Hearne, from “The Quatermass Experiment”)— knows enough about the subject to contribute anything useful after the ex-soldier is murdered in his own apartment. As the mystery deepens, George Adams resurfaces too, with a secret so explosive that he fears for his life to tell the police.

The primary strengths of The Hand are Henry Cass’s driven, hard-edged direction and the sleek competence of the mostly unknown cast. Cass seems to know that he hasn’t a single moment to lose here, and he keeps things moving at a much quicker pace than one generally sees in an old mystery or suspense film. He also doesn’t flinch in the face of the movie’s grislier subject matter, and even gives us a good, close look at the pilfered appendage when Charlie Taplow’s missing hand turns up in another character’s dresser drawer. The cast, meanwhile, has that understated “well of course we’re good— we are English, you know” professionalism about them which always gives me such joy when I see it in action.

The primary weaknesses, on the other hand, are… well, just about everything else, I suppose. But looking closely, it’s probably the script that undoes the biggest share of the good that Cass and his actors had managed to accomplish. Plot holes are pretty much par for the course in low-budget cinema, but in this case, the holes-to-substance ratio puts The Hand in the same category as a pair of fishnet stockings. In fact, it’s easy to get the impression either that about a third of the movie wound up on the cutting room floor, or that writers Ray Cooney and Tony Hilton just never completed the screenplay in the first place. For example, you might want to know why the mysterious Roberts paid Taplow all that money for his hand, how the hand came to be in the possession of the man in whose home it is discovered later, or just what in the hell its new owner could possibly have wanted with the thing. You might also want to know what Roberts was holding over Crawshaw’s head that enabled him to force the doctor’s participation in the hand-buying caper. Don’t bother asking Cooney and Hilton about any of that, however; their lips are sealed on the subject. This ought to be obvious, but in movies of this type, it isn’t enough to reveal who the culprit is. Unless the motive comes out, too, the case cannot be considered closed. And yet even after interrupting the climactic action for a supposedly revelatory flashback, The Hand ends without resolving one goddamned thing, nor is there any indication that the oversight is deliberate. To all appearances, the writers considered their jobs done once they’d brought Munyard and Pollit face to face with their adversary. Come to think of it, maybe there’s one aspect of The Hand that doesn’t bear the fingerprints of Edgar Wallace after all. Lord knows he would never have been so careless.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact