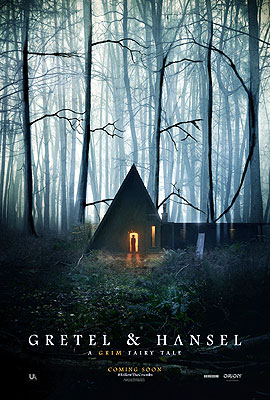

Gretel & Hansel (2020) ***

Gretel & Hansel (2020) ***

Despite all the effort that mamby-pambies of various persuasions invested in obscuring this point from the time of Queen Victoria until roughly the 1980ís, thereís always been very fine line between the fairy tale and the tale of horror. After all, fairiesó that is to say the fair folkó were given that name in the first place by people who hoped that such flattery would placate the terrifying, capricious malice of which the spirits of forest and mountain were reckoned capable. At the same time, the Victorian insistence upon distorting what were once cautionary legends about the unpredictable lethality of the wilderness into vehicles for conservative, Christian moral instruction left at least as lasting an impact on how fairy tales are perceived by modern audiences. Combine those two facts, and fairy tales become uniquely powerful source material for horror stories in the moral-allegorical mode. Curiously, though, the morals of todayís fairy tale horror are arguably the least conservative of any subset within the broader genre. Indeed, because the style has been most warmly embraced by women authors, fairy tale horror as often as not is downright feminist. Thus, even though Gretel & Hansel was written and directed by men, you should have some idea what it means that the two titular kids have had their names switched from their traditional order. Hansel here is a human plot device of the sort that female characters so often get stuck being, while the witch has far more ambitious designs on Gretel than merely to eat her.

This fairy tale begins with a fairy tale of its own. Once upon a time, there was a poor peasant couple whose misfortune was to have a long desired and dearly beloved baby girl just in time for the harshest winter in recent memory. The child wasted no time in getting sick, and consensus throughout the village was that she was unlikely to last until the spring thaw. The father (Jonathan Delaney Tynan) was not the sort of man to be thwarted without a fight, howeveró not even by Mother Nature. He knew of a place far out in the wilderness where there was said to dwell a witch (Melody Carillo) whose enchantments were sovereign over any disease or debility. The peasant sought the witch out despite her fearsome reputation, and persuaded her to extract his daughterís illness. But when the witch drew out the disease, she left a trace of her own magic behind in its place, for the infant, upon growing into mature enough childhood to be played by Beatrix Perkins (also in I Am the Pretty Thing that Lives in the House), exhibited powers of prophecy and second sight. Alas, since all she ever foretold was misfortune, the neighbors soon came to hate and fear the little girló which was fine by her, since she hated all of them, too. In time, her talents grew sufficient to cause calamity instead of just predicting it, and she began to eliminate everyone whom she perceived to be her enemy. Eventually, the roster of the girlís victims included even her own father; for her mother (The Turningís Darlene Garr), that was the last straw. She took the horrid little witch-child to the innermost depths of a trackless forest and abandoned her. No doubt the girl perished quickly, but witches (the evil ones especially) have a way of living on even after their deaths. Supposedly the Girl in the Pink Cap haunts those woods to this day, and woe betide anyone who comes upon her there.

That story is a favorite of a girl on the cusp of adolescence by the name of Gretel (Sophia Lillis, from It and It, Chapter Two). Itís a favorite of her little brother, Hansel (Samuel Leakey) as well, but he likes to listen to it, whereas Gretel likes to tell it. The siblings live on the margins of the very forest where the Girl in the Pink Cap is supposed to make her postmortem home, in circumstances quite similar to the family in the tale, which likely goes some way toward explaining their affection for it. Well, it happens one day that the kidsí father gets as sick as the little baby in the story, only thereís no reclusive conjure-woman to witch him back to health. He dies, leaving his wife (Fiona OíShaughnessy, from Warlock III: The End of Innocence) a helpless travesty of her former self, and the responsibility for earning the family some manner of living has nowhere else to fall but on Gretel. At first, she applies for a post as a maid of all work at the castle of the local squire (Donncha Crowley, of King Arthur and Chaos), but she doesnít care for the direction the interview takes; his lordship seems more interested in the condition of Gretelís hymen than in her domestic skills. When Gretelís grief-maddened mother (who seems to resent the children for surviving when her husband did not) learns that she didnít get the job, she chases her and Hansel from their home with an axe.

After wandering aimlessly all day, the kids happen upon a house that looks as if its owner intends it to offer hospitality to any and all in need. At the very least, the doors are open, thereís bedding all about on the ground floor, and the place is well supplied with candlelight and hearthfire. Unfortunately, the outcast children arenít the only lodgers there tonight. No sooner have they bedded down than their chatter awakens a priapic leper (Jonathan Gunning), who attempts to force himself on Gretel. Things are looking pretty bad for her until her screams awaken their unseen host, a huntsman (Charles Babalola) who turns out to be a crack shot with a bow, even in pitch darkness. Heís got more to offer, too, than rescue and a now much safer place for the kids to stay the night. Although the huntsmanís lifestyle is inconsistent with both child-rearing and any need for domestic servants, he does know the way to a logging settlement far back in the woods. The men there would no doubt be thrilled to have someone to cook, clean, and sew for them. And as for Hansel, he might be much too little as yet to wield an axe effectively, but time and patient instruction should take care of that. The foresters live just a few daysí ride away, along a route which the huntsman maps out for Gretel.

The trouble is, a few daysí ride for a grown man on a horse turns out to be a long trek indeed for two children on foot. What little food Gretel and Hansel were able to take with them runs out before they find any sign of human habitation, and after two or three days with nothing but psilocybin mushrooms to eat, the kids are just about at the end of their endurance. Thatís when they seeó and more importantly, smelló the house. Itís a weird place, built in several clashing architectural styles, and with barely a suggestion of trail leading to it. The door is locked, and the windows are glazed so as to baffle all but the most determined and creative peeping, but the smoke pouring out of the chimney is redolent of cakes, bacon, and heaven knows what other delicacies. Gretel is thinking hard about what to do when Hansel discovers that the windows, unlike the door, arenít latched. Whatís more, heís small enough to wriggle through and see for himself the veritable paradise of mouth-watering food laid out on the immense dining room table. The only trouble is, the owner of the house is a bit on the terrifying sideó a gaunt old hag (Alice Krige, from Silent Hill and Solomon Kane) with skeletal features, grotesquely blackened hands, and eyes like something thatís been dead a good while. Still, she seems friendly enough, even if thereís a clear but untraceable sardonic note in her conversation. And holy shit, but the old broad can cook! It doesnít take long for the kidsí hunger to win out over their wariness.

Over the coming days, the crone displays a surprising eagerness to teach the children things. Upon hearing that Hansel fancies himself a woodsman in the making, she shows him how to grind an axe and sharpen a saw, gives him free access to the tool shed behind her cottage, and then turns him loose in the forest to master the instruments of his prospective vocation. Gretel, meanwhile, receives instruction in herbalism and folk medicineó and when she demonstrates an affinity for those, the witch (for that is now obviously what she is) begins revealing her more arcane knowledge, and dosing the girl with a drug meant to accentuate her natural talent for the supernatural. At first, Gretel finds her unexpected course of study exciting, but it doesnít take long before she notices how her hostess both subtly and not-so-subtly encourages her to leave her brother entirely to his own devices, framing the abandonment of Hansel to whatever destiny may hold for him as emancipation for Gretel. Then there are the dreams, the shoes and toys, and the walled-up door hidden at the back of the pantry. Almost every night, Gretel dreams of either the Girl in the Pink Cap or a severe but beautiful woman (Jessica De Gouw) whose body is heavily tattooed with magical emblems and diagrams. Many of these dreams concern a chamber that may or may not exist somewhere beneath the house, where terrible rites are performedó a chamber which springs immediately to mind when Gretel discovers the aforementioned door. But more importantly, Gretelís dreams all seem to hint at a danger to her brother. Itís therefore disquieting when Gretel notices that the woods all around the witchís cottage are strewn with abandoned toys, in all stages of weathering from like-new to worn beyond recognition, and when Hansel finds a particular grove of trees whose branches are festooned with scores upon scores of childrenís shoes. These omens all grow more troubling still when Hansel really does go missing one afternoon. Has the witch decided to force the issue of Gretelís independence by doing away with her little brother?

Shortly before I went to see Gretel & Hansel, I made the mistake of reading Charles Bramescoís review of the film in Polygon. I call that a mistake because it planted in my head a thematic interpretation of this movie which I doubt would ever have occurred to me unprompted, but which was so obviously apt that it left me unable to read Gretel & Hansel through any other lens. Bramesco sees Gretel and the witch as symbolic of Third- and Second-Wave feminism respectively, with the younger character eager at first to attain the strength, independence, and self-fulfillment which the elder promises as the result of her instruction, but ultimately rejecting at least a few of the core premises of her would-be mentorís philosophy. That analysis resonates strongly with me because of my own fraught relationship with feminism as an outsider to it. You see, I caught on very early in life that the rigidly defined gender roles still lingering from the 19th century were asinine, and that the inequality rooted in them was unjust. But by the time I came of age, in the early 1990ís, the loudest voices in feminism were the radicals of the late Second Wave. Not only were these the ďmen will have to give up their precious erectionsĒ crowd*, but they were also every bit as gender-essentialist and frankly patriarchal as any unreconstructed male chauvinist. They just believed that they should be the ones policing womenís life choices and sexual expression, rather than a bunch of old men with doctorates of divinity. And in fact the Second Wave radfem patriarchs were perfectly content to forge alliances with the actual patriarchy in those areas where their respective conceptions of thoughtcrime overlapped. I therefore spent my youth in the paradoxical and sometimes bewildering position of considering myself an opponent of feminism precisely because I valued equality of the sexes and personal autonomy for women. And it came as a pleasant shock, sometime in the early-to-mid-2000ís, to discover that there was a generational schism occurring within feminism, as women my age and younger increasingly rebelled against the dour doctrines of their elders. Now I canít claim with any certainty that writer Rob Hayes, director Oz Perkins, or even Charles Bramesco himself, for that matter, had similar thoughts observing the past 30-odd yearsí worth of developments within the womenís movement, but now that Bramesco has planted the idea in my head, itís irresistibly tempting to treat Gretel & Hansel as an extended metaphor for them.

What really makes it work in that capacity is that Alice Krigeís witch isnít simply evil. She does horrendous things, with woefully inadequate justification, but in the final assessment, sheís not wrong to decry the raw deal that drove her to take up the black arts in the first place, nor is she wrong about the power and freedom that practicing them has brought her. What she fails to grasp is that her experience was neither universal nor inevitable, and that a more humane response was available to her. When Gretel finally turns on her, it isnít to reject her teachings, but to reject the malice that lies in back of them. No one should be surprised that Gretel & Hansel ends with a witch being burned, but it also ends with a new witch assuming her mantle, making what restitution is still possible for her predecessorís misdeeds, and dedicating herself to finding the ever-elusive Better Way.

The upshot of all that is that Gretel & Hansel is more about a battle of beliefs than it is about menaces to life and limb, making it an extremely abnormal sort of horror movie. It asks us to worry less about whether Hansel will be eaten than about whether Gretel will voluntarily join in the feast. I expect that wonít make sense to a lot of viewers, any more than will Gretelís concluding recognition that the witch was on to something despite the unconscionable actions to which her insights led her. I suspect further that the same viewers will grow excruciatingly bored waiting for Gretel & Hansel to deliver on whatever ghastly business its portents portend. This simply isnít a movie for horror fans who want to be jolted, shocked, or grossed out. But at the same time, it isnít really for horror fans who like a quiet case of the creeps, either. Rather, the dominant mood of Gretel & Hansel is dread, the sense of some awful moment of reckoning headed inescapably in our direction, and that isnít something that comes along often enough to develop a firm fanbase. Nor do we often see movies predicated upon the notion that the temptation to commit evil is scarier than the threat of suffering it. I can already tell that Gretel & Hansel is destined to become a film that I cherish for the rarity of its aims alone, nevermind its considerable success in achieving them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact

* A real thing that Andrea Dworkin actually said.