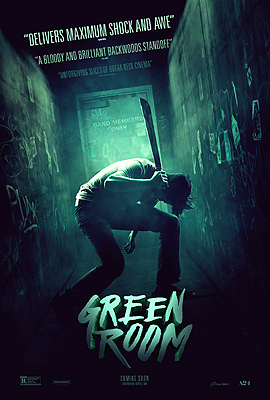

Green Room (2015/2016) ****

Green Room (2015/2016) ****

When I would tell people from outside the punk scene that I was in a band, they usually jumped to certain conclusions about the kind of life I’ve led. Such imaginings were always a great deal more glamorous than the reality. Rock and roll has gotten me laid on exactly two occasions in as many decades, and one of those happened on a seventeen-year delay. Wild parties after the show, when they happened at all, have generally been things I got invited to, but had to turn down; there’s too much equipment to load into the practice space, and my bandmates and I all had day jobs mocking us from the following morning. And since I’ve always been very particular about the circumstances under which I’ll freely debauch, even my most stereotypical rocker dirtbag stories tend to be set at one remove. Instead of doing lines at an aspiring rap producer’s townhouse with a touring band from Israel, for example, I was chatting about the Nightmare on Elm Street series with the aspiring producer’s girlfriend while the guys from National Razor did lines with the Israelis. That isn’t to say I haven’t seen some shit, however. I’ve got tales from the trenches, alright, but they’re mostly about things like getting ripped off. Things like showing up at the venue only to be told that we’re the only band that did so, or to discover that the show isn’t happening at all. Things like spending an entire day in the lobby of a Days Inn, waiting for a mechanic to replace the alternator in the van, and hearing the same goddamned calypso CD, in its entirety, fifteen times in a row over the motel’s PA system. Even the fun stories have a note of hardship to them, like the band we played with in Queens who made ends meet by hanging out in front of sports bars with a sign reading “Kick a punk in the junk— $5!” or the time I slept in a used coffin in Pittston, Pennsylvania.

That’s why I love Green Room. Writer/director Jeremy Saulnier gets it. Before Green Room descends into a form of backwoods horror that I can just about promise you’ve never encountered before, it offers as authentic a look at the hard-luck, hardscrabble existence of a punk band on the road as any I’ve ever seen on film. As well it should, since Saulnier used to play in a hardcore band himself, when he was growing up in Alexandria, Virginia. (Digging into that history, I discovered that I actually met Saulnier back then, although I don’t remember him specifically. My first band, Vrkolaka, played with his band, No Turn on Fred, at some Alexandria church hall in ’94 or ’95. I’m almost positive I still have a copy of No Turn on Fred’s demo tape lying around somewhere.) And even after it goes full Deliverance on us, it does so in a way that’s deeply rooted in the punk experience. No gig of mine ever went off the rails this badly, obviously, but there’s very little reason why one couldn’t have under the wrong circumstances.

The Ain’t Rights are on tour in the Pacific Northwest. It isn’t going very well. Dawn on the date when they’re supposed to play in Portland finds them in a cornfield with an empty gas tank and a mostly run-down battery; evidently Reece the drummer (Joe Cole) fell asleep at the wheel during what was supposed to be an all-night drive, and ran the van off the road. Luckily, they packed a bicycle on which bassist Pat (Anton Yelchin, from Star Trek and Terminator: Salvation) and guitarist Sam (Alia Shawkat, of Final Girls) can ride to the nearest parking lot, and a five-gallon can into which they can siphon fuel from the cars therein. It’s a near thing, but the band makes it to the city not only in time for the show, but also in time for Tad the promoter (David W. Thompson) to record an interview with them for the local college radio station. It isn’t a very good interview, and Tad’s skills as a promoter prove equally lacking. The show— at a hole-in-the-wall Mexican restaurant— is dismally attended, and the Ain’t Rights leave with less than $7.00 each in their pockets and four orders of rice and beans from the kitchen. Tiger the lead singer (Victor Frankenstein’s Callum Turner) is angry enough to pummel Tad, but the promoter escapes by offering to scrape together a second gig for the following afternoon. His cousin, Daniel (Mark Webber, from Antibirth and Uncanny), knows some people in the southern part of the state who can squeeze the Ain’t Rights in as an opening act for a matinee show they had already set up. Tad warns the band, however, that the scene down there is “strictly boots and braces”— skinheads, and primarily various flavors of far-right skinhead, at that.

A quick digression for the benefit of my readers who know skinheads only from the caricatured appearances they make from time to time in mainstream pop culture: Skinheads are not necessarily Nazis, fascists, racists, or reactionaries, although there certainly are far too many skins meeting all of those descriptions. What makes a skinhead a skinhead is fealty to a certain fetishistic notion of the English working class. Naturally, this ideal tends to depart further from any reality that ever existed the farther one gets from the British Isles. Generally speaking, skinheads value brotherhood, loyalty, patriotism, and physical courage. They also value drunkenness, hooliganism, recreational violence, and a paradoxical combination of in-group authoritarianism and knee-jerk opposition to outside authority. As the latter ought to imply, skinheads like belonging to groups, even if those groups are largely imaginary. They often go in for trade unionism, sports fandom (international football especially), street gangs (although they prefer to call them “crews” or “firms”), and not conspicuously organized “organizations” like Skin Heads Against Racial Prejudice. You’ll notice that fascist movements scratch every one of those itches. In fact, we’re talking about the same complex of itches that fascism was designed to scratch in the first place, which is probably why skins got such a head start over all the other youth tribes in developing an intractable Nazi problem. In any case, skinheads who aren’t Nazis generally find their far-right cousins as intolerable as everyone else does. The result is that Nazi skins form a counterculture within a counterculture, relying on social networks that exist under the underground. They have their own small presses, their own record labels, their own online and mail-order distribution networks. Their bands, unwelcome at most venues open to underground rock music, have to play on a circuit all their own. And in the northwestern quadrant of the United States, among the most reliable places for Nazi skinhead bands to perform are the compounds of right-wing militia groups whose leaders recognize the power of the music as a recruiting tool among the youth, even if they don’t identify as skinheads themselves.

The point is, the Ain’t Rights know all that, so they catch on at once when the venue for Cousin Daniel’s consolation gig turns out to have been converted from some kind of farm outbuilding in the middle of Christless nowhere. Gabe (longtime Saulnier associate Macon Blair, also in Hellbenders and Murder Party), who runs the place in its capacity as a performance space, hustles the band into the backstage waiting area with a terse “Soundcheck’s in fifteen minutes. You go on in twenty.”

“They run a tight ship,” observes one of the Ain’t Rights.

“Yeah, but it’s a U-Boat,” replies another, eyeing the racist graffiti and fascist ephemera displayed all over the place.

That’s when Tiger has what he freely admits is a really bad idea: what if the Ain’t Rights began their set with a cover of the Dead Kennedys classic, “Nazi Punks Fuck Off?” It’s the sort of provocation that all punk rockers have in their fucking blood, so of course they actually do it. What’s surprising is that they seem to win over a substantial fraction of the crowd with the rest of their set. Afterward, Gabe pays them the promised $350, no questions asked, and for a little while it looks like the Ain’t Rights will just pack their shit and get back on the road unmolested. But then Pat remembers that he left his phone charging in the green room. He pops in to get it just in time to catch the immediate aftermath of an altercation between Werm (Brent Werzner, of The Argentum Prophecies), one of the members of Cowcatcher, and Daniel’s girlfriend, Emily (Taylor Tunes). It’ll be a while before we have enough information to deduce why, but Werm stabbed Emily in the fucking brain, and there’s no plausible way to pretend that Pat didn’t see the dead girl’s body. Within minutes, the whole band is locked in the green room with Emily’s friend, Amber (Imogen Poots, from Fright Night and Centurion), under guard by the aptly named Big Justin (Eric Edelstein, of Patchwork and The Hills Have Eyes 2) and a proportionately sized revolver.

Why not just kill Amber and the Ain’t Rights on the spot? Because Green Room is set in a nearer approximation of the real world than most horror movies, and in the real world, people have families and friends and coworkers who will notice if they disappear unexpectedly. Sometimes, they even tell those people where they’re going when they leave the house. In the real world, there are cops and laws and prisons, and Pat had time to call 911 before he and his bandmates were locked up. Granted, Gabe and Big Justin didn’t give him a chance to say much, but now some of those cops are on their way to the compound to investigate a stabbing. That part Gabe thinks he can handle. He pays off one eager young recruit to submit to being gouged a few times with a pen knife, and another one to take the fall for “attacking” him. Everything else, though? It’s way above Gabe’s pay grade. So he does what any sensible subordinate would do in his situation, and calls in the boss. That would be Darcy (Patrick Stewart, from Star Trek: First Contact and The Doctor and the Devils), the white nationalist militia patriarch whose land Gabe’s nightclub occupies, and the de facto leader of all the worst Nazi skinhead motherfuckers in the county.

Arriving upon the scene, Darcy deems the whole situation a pig-fuck. (And what a joy it is to hear Patrick Stewart, of all people, say so.) Don’t get him wrong, that was slick work with the cops, the kids, and the pen knife, but just look at this mess! The whole place is crawling with people, every one of them a potential witness to anything Darcy might have to do backstage, and there’s still one more band yet to play. They’ll all have to be gotten rid of somehow before anything can be done about Amber or the Ain’t Rights. Then there’s the question of why Werm stabbed Emily in the first place, which turns out to have something to do with a traitor in the skinheads’ midst. Worst of all, Gabe didn’t count on Reece knowing some kind of crazy MMA groundfighting shit. What Darcy finds in the green room is no longer a bunch of cowed prisoners under armed guard, but one of his own best men held hostage by the very interlopers whom he needs to eliminate. Still, Darcy and his minions are holding most of the cards here. An excuse can be found to shut down the show and clear the area of unreliable eyes. Darcy can easily summon more than enough manpower and firepower to overwhelm the Ain’t Rights, martial arts and captured .44 magnum notwithstanding. He also has plenty of time and a completely free hand to arrange the scene to fit whatever cover story he ultimately concocts to account for the band’s disappearance. And of course, all of this is taking place on Darcy’s own land, so he’s got the home-court advantage. If Amber and the Ain’t Rights want to make it out of here alive, they’ll have to be clever, ruthless, and almost suicidally brave, and they won’t have much time to get into the necessary frame of mind.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Patrick Stewart play an all-out villain before, and I know I’ve never even imagined him as a neo-Nazi militia leader and backwoods heroin kingpin. He’s terrific, though, in both the obsolete, literal sense of that word and the current, figurative one. Green Room takes everything one expects from Stewart, and turns it upside down. Darcy’s mind is every bit as keen and orderly as Captain Picard’s or Professor Xavier’s, and he projects the same overwhelming air of competence and authority. He may be soft-spoken, elderly, and a mere shadow of his former physical self, but it never seems incredible for a moment that so many young troublemakers who respect only strength and violence would unquestioningly obey his every word. At the same time, though, Green Room is admirably realistic about Darcy’s actual capabilities. The secret to his power is his ability to leverage control of a situation. The more chaos the Ain’t Rights are able to foment in order to take that control away from him, the less formidable Darcy becomes. As one of the survivors bemusedly puts it during the final confrontation the following morning, “You seemed so scary in the dark.” Alone, in the gray light of an Oregon dawn, he’s nothing but a little old man full of fear and impotent hate.

That kind of villain won’t work for just any story, of course. In order to be convincing as both a character and a threat, a baddie like Darcy needs a deep enough grounding in real-world logic for his methods to stand scrutiny. Otherwise, he’s either Fantomas in a bomber jacket or a ridiculous, puffed-up crank who should be hollering at the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn. Saulnier makes a point of showing how much planning and work it takes to maintain a criminal empire too small to bribe its problems away. He shows the talent for quick thinking and improvisation that a man in Darcy’s position requires, too, like when the militia leader calls in Clark (Kai Lennox), the man who breeds and trains the pit bulls for the gang’s dog-fighting matches, to contribute a couple of his battle-hardened champions to the effort against the Ain’t Rights. The drug lab in the basement of the club is a nice touch as well, neatly disposing of the oft-ignored question of what’s funding all this evil. Best of all, Saulnier is realistic enough to posit a limit to the skinheads’ loyalty. I don’t just mean the “traitor” (which is to say, the skinhead who’d decided he wanted out of the gang before the Ain’t Rights even pulled into the parking lot), either. As the green room captives increasingly reveal themselves as a force to be reckoned with, Darcy starts encountering discipline problems. One skinhead even surrenders to what’s left of the band in the end, wearily announcing, “I want to go to jail.” Ultimately, Green Room portrays neither the hyper-competent heroes typical of action movies on premises comparable to this one, nor the hyper-competent villains you’d expect to see in their horror counterparts. Neither side is really ready for what they get into here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact