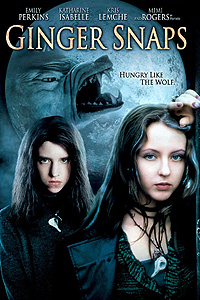

Ginger Snaps (2000) ****

Ginger Snaps (2000) ****

I had meant to cover Ginger Snaps as part of my “Catching Up with the Aughts” project a few months back, but only the sequels were in stock whenever I went to the video store to get it. Let me just say that I’m really glad I finally found this movie— in fact, I don’t think I’ve been so thrilled by a film that flew under my radar in its initial release since I saw Dead Alive at long last about ten years ago. Not that Ginger Snaps much resembles that movie, you understand. Although it does start out as a macabre black comedy, it eventually undergoes more transformations than the Smog Monster, functioning as straight horror, as puberty parable, and as a nearly heartbreaking meditation on sibling loyalty and its limits by the time the credits roll. And through it all, Ginger Snaps is also the best damn werewolf movie since I don’t know when.

The title, incidentally, should be read not as the name of the popular cookie variety, but as a sentence encapsulating what’s about to happen. The Ginger in question is sixteen-year-old Ginger Fitzgerald (Katharine Isabelle, from Disturbing Behavior and Freddy vs. Jason), who would be the least popular girl in Bailey Downs High School were it not for her slightly younger sister, Brigitte (It’s Emily Perkins). Ginger, at least, has the advantage of being strikingly beautiful in a slightly off-kilter way; Brigitte is just a frumpy, sullen dork, her social standing further compromised by academic prowess sufficient to have let her skip a grade. The Fitzgerald sisters are about as morbid a pair of misanthropes as you’re likely to find anywhere. Their main hobbies are staging and photographing elaborate tableaux of their own deaths (a montage of these images and their creation plays under the opening credits; my favorite is the drain-cleaner tea party in the backyard) and trading predictions about the horrible fates destined to befall their classmates. Their mutual devotion, meanwhile, is codified in the suicide pact they made when they were eight and seven years old respectively: “Out by sixteen or dead on the scene, but together forever. United against life as we know it.” Note that the terms of that pact require Ginger’s death at some point this very year, unless she finds an immediate escape route from her dismal little town, and that she’s consequently been brainstorming lately for suitably theatrical ways to off herself. Mom (Mimi Rogers, of Lost in Space and Penny Dreadful) and Dad (an actor by the delightfully apt name of John Bourgeois) are apparently completely oblivious to all of this.

With the fulfillment of their suicide pact imminent, you’d think the girls would have bigger things to worry about than the animal that’s been slowly but surely massacring all the pets of Bailey Downs— they themselves certainly think so. But on the very night when the late-blooming Ginger finally receives her first period, a big, fierce creature attacks the sisters, and injures Ginger before Brigitte can wrest her away from it to take flight. The animal— whatever it is— gives chase, and it is within scant feet of catching the girls when it is run over and crushed to a pulp by the van belonging to Sam (Chris Lemche, from Final Destination 3 and eXistenZ), the brilliant but easily underestimated kid who grows, manufactures, and/or sells most of the illegal drugs to be had in Bailey Downs. The extremely thorough destruction of the beast’s body makes it impossible to determine what in the hell it really was, but somehow neither of the obvious candidates— a very large dog or a fairly small bear— seems quite credible. (Mind you, that’s at least partly because the creature effects in Ginger Snaps are also less than credible. That weakness— the movie’s sole really serious one— isn’t so obvious in the foregoing scene, but the much more visible animatronic monster that figures in the climax is so sad that the filmmakers would almost have been better off taking the old Jack Pierce approach.)

There’s one more thing I should mention about the Fitzgerald girls’ run-in with what they’d been calling the Beast of Bailey Downs: the moon was full when it happened. That fact weighs increasingly on Brigitte’s mind over the coming days, as stranger and stranger things start happening to her sister. To begin with, the wounds left by the creature’s claws scab over with shocking rapidity, although it still takes some time for them to heal completely. Also, the skin surrounding those cuts sprouts freakish quantities of hair as the repairs progress. Meanwhile, Ginger starts acting rather unlike her former self. She becomes much more assertive, first in the sense that she begins reciprocating and encouraging the interest that a boy named Jason (Jesse Moss, also of Final Destination 3, and of yet another damn movie called The Uninvited as well) takes in her, and also in the sense that she pounds the living shit out of Trina Sinclair (Danielle Hampton), princess of the Bailey Downs in-crowd, the next time she sees Trina abusing Brigitte during gym class. Ginger even joins Jason and a friend of his in smoking some of Sam’s weed. The latter set of changes tends to mask the significance of the former, for they make it easier for all concerned to spin Brigitte’s worries about her sister as discomfort with the fact that Ginger is growing up, and thereby moving beyond the insularity that the two girls have hitherto shared. But when Ginger butchers the neighbors’ irritating dog in a manner reminiscent of the Beast of Bailey Downs— to say nothing of when she starts growing a tail— there can be no further question that something far out of the ordinary is going on with her.

That makes it convenient, in a way, that Sam saw enough of the creature he flattened with his van that night to have his own weird misgivings about what it might have been. A week later, when he begins comparing notes with Brigitte, it dawns on her that here is one other person who might not dismiss her suspicions about Ginger as insane. However, Brigitte also thinks it important to keep her sister’s secret, so she proceeds in her talks with Sam on the pretense that it was her, and not Ginger, who was injured by the presumed werewolf. Sam may be willing to consider the reality of lycanthropy, but he rejects out of hand the notion that there could be anything magical about it. If there are werewolves, and if those werewolves are able to pass their condition along to other people, then there must be a contagion of some kind at work— a virus, a bacterium, a parasitic protozoan. Sam also makes a connection between his pathogenic theory of lycanthropy and the traditional belief that silver is deadly to werewolves, because he’s had quite a number of piercings done, and it’s been his experience that those made with silver jewelry are far less prone to infection than those using other metals. For the time being, he suggests that Brigitte give herself (or rather, her sister) a body-piercing somewhere, adorning it with silver in the hope that contact between the metal and her bloodstream will at least impede the progress of the transformation. He even gives Brigitte one of his own rings with which to do it. Sam also sets to work cross-referencing all the werewolf lore he can find with the knowledge of botany and pharmacology he’s picked up as a result of his efforts to raise bigger and better marijuana crops, with an eye toward devising some herbal remedy for the condition.

The silver (obviously a longshot to begin with) fails miserably, but Sam’s research turns up something very promising— a plant akin to wolfsbane called monkshood, which unlike the former herb is easy enough to find in modern suburban plant nurseries. The trouble is, monkshood blooms in the spring, and it’s now the last week in October. Fortunately, that problem is solved neatly enough when Mrs. Fitzgerald brings home some bouquets of dried flowers that happen to contain several sprigs of the stuff. Much more serious a concern is Ginger’s ever-increasing aggressiveness and ever-poorer impulse control. It’s bad enough when she has very rough and very unprotected sex with Jason, infecting him with lycanthropy. (I like the ambiguity here over whether it’s the scratching and biting or the venereal mixing of body fluids that spreads the curse to Jason.) Worse still comes when Ginger kills Trina Sinclair, kinda-sorta by accident, in the Fitzgeralds’ own living room! Mom and Dad aren’t going to be happy about this…

In a way, it’s a rather like a mash-up between the scripts to Heathers and Wolf. Like the former film, Ginger Snaps unfolds from the perspective of a girl consumed by loathing for her social circumstances, who unexpectedly gets exactly what she thinks she wants— the total expungement of banality and normality from her life, together with an opportunity to wreak tremendous destruction on everything she despises— and discovers that it’s far more horrifying than it’s worth. It also shares some of Heathers’ mordant sense of humor, particularly early on, before Ginger’s transformation seems to threaten much worse than massive social embarrassment. There’s even a touch of similarity between Sam and Christian Slater’s character in Heathers, although the two boys’ roles in their respective stories are of course very different. The resemblance to Wolf lies partly in the structure of the plot and partly in how the two movies treat the process of turning into a werewolf. Like Wolf, Ginger Snaps posits a distinct short-term upside to lycanthropy, a tremendous increase in confidence, power, and virility that comes at the eventual cost of the werewolf irreversibly losing his or her humanity. The mechanics of that tradeoff, and its significance for both the werewolf and those who care about him or her, set both the tone and the pace, dictating how and when the emphasis of each film shifts from its dramatic and/or comedic concerns toward horror.

Ginger Snaps is a much more forthright monster movie than Wolf, however, and it has a lot more heart backing up its snark than does Heathers. Most importantly, the latter difference manifests itself in a way which demonstrates that although the present filmmakers might sympathize with the Fitzgerald sisters’ exaggerated misanthropy, they don’t actually share or condone it. In fact, the most striking thing about this movie is how utterly unafraid it is to be outright sappy— we’re talking, after all, about a film in which the main focus is on two vaguely gothy sisters forced to sort out adult versions of their feelings for each other (and for their parents as well) by a metaphor-soaked version of the growing apart that so often accompanies growing up. Ginger Snaps could very easily have gone horribly off-course into ABC After-School Special territory. That it doesn’t testifies to the abilities of the four people most central to its creation: director John Fawcett, writer Karen Walton, and stars Emily Perkins and Katharine Isabelle. It’s an odd situation that lot were in while Ginger Snaps was under production. The “adults” behind the scenes had very little directly relevant experience, for Walton had written nothing longer than a TV episode, while Fawcett had directed but a single feature film prior to 2000. Perkins and Isabelle, in contrast, were old hands at the acting business despite being only 23 and nineteen years old, respectively, both having gotten their start in front of the camera way back in 1989. We might therefore think of Ginger Snaps as a rare and wonderful upside-down combination of beginner’s moxie and time-honed professionalism. Fawcett and Walton either didn’t know or didn’t care about the things they weren’t “allowed” to do in a teen horror film, and the two lead actresses performed as though these were the roles they’d been dreaming of playing since the day they stopped being eligible for guest spots on “Sesame Street.” They’d have been justified in such dreaming, too, if that were really the case. Especially in comparison to what one typically sees in teen-focused horror films, the Fitzgerald sisters are extremely well rounded and fully developed characters, and demand of both actresses the full use of their ranges— which makes it an utter joy to see the parts filled by performers who actually have ranges! Isabelle, for example, spends most of the second act having to repeatedly turn on a dime between antithetical emotional states related on the one hand to Ginger’s exultation in her new-found power and on the other to her horror at her escalating loss of self. She manages it handily, and Perkins proves even more agile. Frankly, I can’t decide which is the more welcome change of pace, a pair of young actresses with abilities of this magnitude, or a writer and director willing to trust such actresses enough to demand so much of them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact