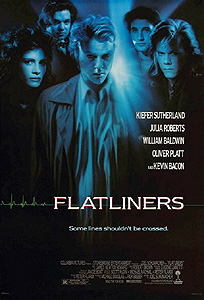

Flatliners (1990) **

Flatliners (1990) **

Sometimes I think Iím the only person who doesnít hate Flatliners, and Iím always just about certain that Iím the only one who regards it with genuine nostalgia. The latter has little to do with the movieís actual merits, you understand. Itís simply that this film has a lot of strong positive associations for me, because I originally saw it as part of the first date I ever went on. First love alters the complexion of everything even tangentially connected to it, and seeing Flatliners at Marley Station Mall in the spring of 1990 was the occasion for way too much happiness for me ever to dislike the movie itself with any intensity. But even apart from my bias in its favor, I donít think Flatliners is nearly as bad as it is generally held to be. It certainly isnít good, but compare it to some of the other crap that director Joel Schumacher has inflicted upon us over the years, and I believe youíll agree that we got off easy this time.

Medical student Nelson Wright (Kiefer Sutherland, from The Lost Boys and Mirrors) takes a quick and not strictly speaking allowed tour of a building on his universityís campus that is currently closed for renovations, and having apparently decided that it suits some purpose of his, declares, ďToday is a good day to die.Ē Nelson then spends the rest of the day pestering three of his highest-ranked classmatesó Rachel Manus (Julia Roberts, whom weíre not likely to see around here again unless I someday go mad enough to review Mary Reilly), Joe Hurley (William Baldwin, of Sliver and Virus), and Randy Steckle (Lake Placidís Oliver Platt)ó about joining him this evening for some hush-hush undertaking. Meanwhile, David Labraccio (Kevin Bacon, from Stir of Echoes and Hollow Man), the schoolís number-one med student, is over at the teaching hospital, getting himself suspended for operating on an emergency patient while all of the real doctors are momentarily too busy to do anything for her. True, Labraccio very likely saved the womanís life, but medical schools are pretty much founded on the principle that people who are not entitled to call themselves ďdoctorĒ are also not allowed to do shit like that. Nelson will be dropping by Davidís apartment to pester him, too, before the afternoon is out.

Whatís going on here is that Wright has conceived what is either a brilliant plan or a monumentally stupid one to establish experimentally once and for all whether or not thereís really such a thing as life after death. He wants to smuggle some equipment into that shut-down building after everyone with legitimate business on that part of the campus has gone to bed, and have his four colleagues use it to stop his heart according to a precisely controlled protocol, then revive him exactly one minute after the EEG stops registering brain activity. Labraccio, Manus, Hurley, and Steckle are sensibly reluctant to sign on for anything so obviously dangerous and ethically iffy, but in the end, these people are all much too ambitious to resist the allure of a definitive scientific answer to a question that the humanities have grappled with inconclusively for millennia.

Flatliners wouldnít be much of a movie if there were nothing on the other side, of course, so Wright does indeed experience something during his 60 seconds of biological non-existence. It doesnít bear much resemblance to the accounts of near-death experiences that Manus collects so obsessively (for cryptic reasons that have something to do with a lost loved one), however. He sees no tunnel, no light, no angelic guide, nor does he find himself floating incorporeally over his untenanted body. Instead, Nelson becomes a detached spectator to a moment from his own past, as he and two other boys run through an overgrown field with a tubby and ungainly dog. One minute isnít nearly long enough even to hint at the significance of this particular scene under the current circumstances, but Wright is conscious all the while of a tremendous inner peace and an untraceable, impersonal sense of benevolence directed toward him. On the whole, he finds his adventure in the next world a positive experienceó and all the more so given that the experimentís success means that he personally has for all practical purposes just invented a whole new branch of science. It would be going too far to say that the other four participants forget their earlier reservations in the wake of Nelsonís triumph, but in light of the bidding war between Rachel and Joe that breaks out later that night over which of them gets to go next, one has to conclude that some minds have been changed. Hurley proves the bigger risk-taker, offering to stay dead for a minute and a half versus Manusís 1:20, and the five thanatonauts agree to reconvene the following night despite the continued misgivings of Steckle and Labraccio. Those misgivings might be just a little stronger and a little more generally held if Wright would mention a hallucination he has shortly before the group breaks up. The quality of the light goes strange for a while, and he sees the dog from his vision (which he now recognizes as a childhood pet) nosing plaintively around in an alley, outfitted with a brace around its hindquarters as if it had suffered some serious spinal injury. That last detail seems to mean something to Nelson, but itíll be just about the end of the film before we discover exactly what.

One thing you have to understand about Joe Hurley before we proceed any further: heís an incorrigible horndog every bit as untrustworthy as the voyeuristic apartment superintendent whom William Baldwin would play in Sliver three years later. Joe is engaged to a girl named Anne (Hope Davis, from a version of The Lodger that I didnít realize existed until just now), apparently his old college sweetheart. Anne is pursuing an advanced degree of her own at another school, and Joe has taken advantage of their separation throughout each term to sleep with every female whom he could talk out of her panties. Seriously, there are hair-metal frontmen who donít get half this much ass. Furthermore, Hurley betrays his army of girls on the side just as systematically as he betrays Anne, for he makes a point of surreptitiously videotaping each of his conquests and maintaining a secret library of these pornographic video diaries. This matters because Joeís trip to the Great Beyond takes the form of a recap of every moment of physical intimacy with a woman that heís experienced since his breastfeeding days, and his post-return hallucinations involve all the girls heís found, fucked, and forgotten over the years popping up to reproach him for his inconsiderate and duplicitous tomcatting. Wrightís hallucinations, meanwhile, become a great deal more serious and a great deal less hallucinatory. One of the other boys from his vision (Joshua Rudoy, of Harry and the Hendersons) now takes to accompanying the dog, and despite the vast and obvious imbalance in size and apparent strength between them, the imaginary child somehow manages to beat the crap out of Nelson every time they meetó and in a totally non-imaginary manner, requiring totally non-imaginary stitches, I might add.

Neither man says a word to the others about these weird goings-on until after David and Rachel have taken their turns, bringing home paranormal hitchhikers of their own. (Steckle remains content throughout with his post at Mission Control.) Labraccioís otherworldly stalker is a little black girl whom he recognizes as Winnie Hicks (Kesha Reed), the kid who was invariably dead last in his elementary schoolís pecking order. As for Manus, she has to contend with her father (Basic Instinctís Benjamin Mouton), who killed himself in the most melodramatic fashion possible immediately after the seven-ish Rachel walked in on him shooting up heroin in the upstairs bathroom. Rachel didnít know what he was up to, and Schumacher treats it as a major revelation when Junkie Dad eventually explains it to her, but any halfway with-it viewer will instantly apprehend the significance of Old Man Manusís posture during Rachelís death-trip vision as he sits, fully clothed, on the toilet with his head bowed and all of his attention focused on his unseen arms. Neither one of these hauntings (or Joeís either, really) is in the same league as Nelsonís, though, because all Winnie ever does is bombard David with euphoniously foul-mouthed insults (ďShit-face rat-turd aaaaaaaaaaaaaass-lickiní son of a bitch!Ē), while Junkie Dad just hangs around looking doleful in the crapper. Nevertheless, itís Labraccio who figures out how the thanatonauts might be able to get quit of the visitations. After Nelson suggests that theyíre all being pursued by their past sins, David hits upon atonement as the route to peace. Thatís fine for him, as itís little trouble to look up Winnie Hicks (played as an adult by Kimberly Scott, of The Abyss) and apologize for being such a horrible little shit to her when he was a boy, but Joe could easily spend the rest of his life tracking down all the women in his collection, and itís debatable whether heís really sorry for his conduct in the first place. Iím thinking sincerity probably matters a great deal under the circumstances. Rachel too might find it a tall order to make whatever amends her dad is looking for, seeing as heís been dead for, like, fifteen years. And Nelsonís old playmate, Billy Mahoney? The reason heís so much more aggressive than any of the other shades is that Nelson actually killed himó cornered him up a tree with whomever that third kid was, and chucked stones at him until he fell and busted his head. ďIím sorry, BillyĒ really doesnít seem likely to cover that, even if Nelson could figure out how to get the message across.

Thereís something about Flatliners that I canít quite figure out. Nelson Wright and his colleagues get themselves into trouble by poking around in the inner metaphysical workings of death, but the agents of that trouble are not necessarily ghosts in the ordinary sense. Billy Mahoney certainly seems to be one, as does Rachelís father, but Winnie Hicks is both very much alive and no longer the child whom David Labraccio remembers tormenting in the schoolyard all those years ago. Whatís more, all those spectral women haunting Joe Hurley have not only living doppelgangers, but living doppelgangers who for the most part are completely unaware of what Joe did to them! Davidís and Joeís supernatural persecutors canít be ghosts, and the shades of Hurleyís harem canít even be manifestations of the real womenís feelings of betrayal, so what the hell are they, and why would venturing beyond death open one up to attack by them? Obviously thereís a fair chance that weíre just looking at laziness on the part of writer Peter Filardi, mere evidence that he did not think through the full implications of the scenario. But thereís also a chance that Flatliners is something rather unusualó a horror movie with a specific theological perspective. What if Nelson is literally right when he refers to the things vexing him and his fellow thanatonauts as their sins? What if the place they visited on the other side was not simply the afterlife, but Purgatory in particular? That would clear up a lot of the movieís apparent inconsistencies. For starters, it would explain why Wright, Hurley, and Labraccio all report a sense of cosmic benevolence, even though they were in the presence of things that seem to mean them harm once transported to the world of the living. Under this model, we might assume that by dying long enough to enter the hereafter, Nelson and the others trigger the apparatus of expiation, but their return to life interrupts Godís washing machine midway through the first scrub cycle, and their souls are reinstalled in their bodies still soaked with bleach and detergent. It would also explain why Hurley ceases to be troubled by imaginary women after Anne drops in for an unexpected visit, and discovers his video trophy caseó no more need to seek atonement for that sin when heís actually paying for it, right? And finally, it would explain why Rachel, alone among the experimenters, feels no nimbus of divine goodwill while sheís on the other side, for the existence of Purgatory would imply that Rachelís fatheró a suicide, rememberó was attempting to communicate with her from Hell. I really want this to be something that Filardi and Schumacher set out to do, not just because it would add an extra layer of interest to a film that could use a few more of those, but more importantly because it would mean that they respected their audience enough to trust that we would figure it all out without a convenient Roman Catholic priest showing up in the third act to explain everything. Besides, isnít it about time the horror genre found a use for Catholicism more imaginative than burning witches or chasing the Devil out of Linda Blair?

If, on the other hand, there really is nothing more than lazy writing to account for the weird mix of elements that comprises the hauntings in Flatliners, then weíre left with a movie that has very little to say for itself. With the exception of Billy Mahoney, these are some pretty anodyne bogeymen, and even Billy is the sort of thing that works better in print than it does on celluloidó when youíre looking right at it, itís rather difficult to buy into Kiefer Sutherland getting his ass kicked by a ten-year-old. Even if there were no way at all to stop her, Iím pretty sure Iíd eventually get used to being shit-talked by a phantom schoolgirl, and itís hard to see why an inveterate jerk-ass like Hurley would be much inconvenienced by the Ghost of One-Night-Stands Past once heíd ascertained that the uncanny guilt-tripping was in at least some sense real, that he wasnít simply losing his mind. And Rachelís haunting just plain doesnít work. The real story behind her fatherís suicide is something she should have been able to piece together for herself by the time she was in high school; that she still literally blames herself for his death makes no sense unless we presume that her understanding of human psychology has not advanced in the slightest since she was in the second grade. The other trouble with Rachelís plot thread is Julia Roberts. Iíve never been able to understand how she became such a big star, and seeing her again here, on the very eve of her emergence into the limelight, has left me more baffled than ever. Kiefer Sutherland is an okay actor with a special talent for bullying bastards. Kevin Bacon is somewhat more versatile, but to all outward appearances, his biggest assets are a good work ethic and a better agent. Oliver Platt was an all-purpose eccentric for people who couldnít afford Johnny Depp, and William Baldwin is the Smirk That Walks Like a Man. With that kind of competition, itís sort of impressive that Roberts still manages to stand out for her inadequacy in Flatliners. In a film that seems to aim no higher than to be more or less adequate, she is easily the greatest single liability.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact