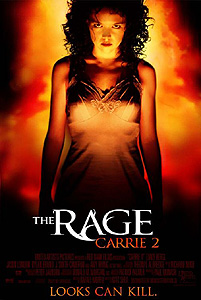

The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999) *½

The Rage: Carrie 2 (1999) *½

I’ve said it before, and this seems like an excellent time to say it again: there’s nothing wrong with sequels, just so long as their creators make an honest effort to do justice to the original film. In general, that’s my opinion, and I’m sticking to it. There is one narrow area, however, in which I share a bit of the knee-jerk sequel aversion that one encounters so often among our grumpier cinema critics. When a movie was adapted from the writings of a still-living author, and when that author wrote no sequels of his or her own, it bugs me in a way that I can’t entirely justify to see the film version sprout continuations— especially if there’s a long lag-time between the first movie and its successors, and especially if the direct adaptation was good, but the baseless sequel is a piece of shit. It strikes me almost as an analogue to the legal concept of double jeopardy. If an author’s story has already survived being thrown to the fuck-up artists of Hollywood once, it seems gratuitously nasty to give them another shot while the story’s originator is around to see it, and the more time goes by between attempts on the tale’s life, the more gratuitous it feels. In the case of Carrie, the Brian De Palma movie had its flaws, but still did more or less right by Stephen King’s novel. The sequel that emerged after a nearly unheard-of 23-year interval is a different and altogether weirder matter. With in-name-only sequels as prevalent as they were in 1999, the mere presence of a returning major character— played by the original actress, even!— is enough to indicate that The Rage: Carrie 2 was made with a certain amount of respect for the source material, while the fact that it received theatrical release suggests a bit of ambition on its creators’ and distributors’ parts. Nevertheless, Carrie 2 is no less junky, pointless, or tone-deaf than the quickie direct-to-video cash-in we might have expected.

The obvious obstacle facing any attempt to sequelize Carrie is that the title character is pretty inescapably dead at the end of the film. A 1987 sequel would no doubt have solved the problem by bringing Carrie White back as a supernatural slasher (played, inevitably, by someone much cheaper and much more siliconey than Sissy Spacek), but horror movies aimed at teenagers who weren’t technically old enough to buy tickets to them had thankfully grown up at least a little bit by 1999. Instead, The Rage takes the hazardous but manifestly more sensible route of replacing Carrie with a new psychokinetic kid. Her name is Rachel Lang (Emily Bergl— or at any rate, she’s Emily Bergl for most of the film), and we meet her on the night when her mother, Barbara (J. Smith-Cameron), was hauled away to Arkham Asylum. (I leave it to you to ponder whether that makes her Herbert West’s neighbor, or the Joker’s.) Barbara, you see, had become convinced that her daughter was possessed by the Devil, and that Satan had endowed Rachel with the power to move and destroy objects using nothing but her mind. We of course know (given which movie this is a sequel to) that the girl really does have such power, but the outside world isn’t buying it. After the cops barge in to interrupt some weird sort of exorcism ceremony, it’s off to the funny farm for Barbara, while Rachel winds up the foster child of two trailer-trash types called Boyd (X bassist John Doe, whose other screen acting gigs include Black Circle Boys and Liquid Dreams) and Emilyn (Kate Skinner).

By the time she’s a senior in high school, Rachel is a rather withdrawn and socially isolated teen, her only close friend an even more introverted girl by the name of Lisa (Mena Suvari, from Kiss the Girls and Steve Miner’s version of Day of the Dead). Even so, she’s not at all the broken, helpless thing that Carrie White was. Sure, she has her problems with the school authorities, and with the nasty clique of popular girls led by head cheerleader Tracy (Charlotte Ayanna, of The Thirst and The Insatiable), but on the whole, she seems very well adjusted to her maladjustment, if that makes any sense. Lisa is the fragile one here, so it’s terribly unfortunate that she spent last Saturday night losing her virginity to a football player named Eric (Zachery Ty Bryan). Mark the quarterback (The One’s Dylan Bruno) has organized his teammates into a competitive league of a different sort, devising a system for assigning point values to every girl in school, and inciting the rest of the jocks to make a game out of bedding as many of them as they can before the end of the semester. I’m not exactly sure what the boy with the highest score come graduation day is supposed to receive, but I guess one might argue that Mark’s is a game in which playing is its own reward. The point is, Eric and Lisa have drastically different understandings of their coupling’s significance (for the record, Lisa was worth a measly four points), and Lisa takes it rather hard when Eric disabuses her of her more romantic conception of events. So hard does she take it, in fact, that she takes a header off the roof of the school that very morning, and splatters herself all over some unsuspecting schmuck’s car. Rachel is among the first on the scene after it happens.

That’s where Sue Snell (Amy Irving, revisiting her old role) comes in. You remember Sue Snell— she was the popular girl whose remorseful attempt to atone for her tribe’s merciless beastliness toward Carrie White launched the train of events that culminated in the Prom Night Holocaust 20-odd years ago. She’s a guidance counselor now, which means that the school administration is going to expect her and Rachel to spend a lot of time together in the aftermath of Lisa’s death. Now as we all know from about three fifths of the psychic powers movies ever made, psychokinesis is keyed to emotional state, and is likely to manifest itself spontaneously in stressful situations. Stressful situations like (for the sake of argument) having one of the authority figures whom you instinctively regard as your enemies interrogate you in a well-meaning but misguided manner immediately after your best friend’s totally mysterious and very public suicide. Small, weird disturbances occur every time Miss Snell brings Rachel into her office, and while most people in her position might think nothing more of them after the puzzlement of the moment wore off, Sue finds exploding paperweights and coffee cups pitching themselves off of desktops to be disquietingly familiar.

The reason why Lisa’s death is totally mysterious to Rachel is that Lisa told her what she’d done over the weekend, but refused to reveal whom she’d done it with until lunchtime, when she’d have a chance to introduce her new “boyfriend” in person. Lisa didn’t live to see lunchtime, though, and she never showed Rachel the suicide note that she left in her locker, either, so the latter girl is in the dark for the moment regarding her friend’s motives. That’s about to change, however, for several reasons. Lisa’s note didn’t name any names or give any specifics, so when Sheriff Kelton (Clint Johnson) gains access to it as part of the investigation into the girl’s death, he naturally turns to Rachel for interpretational assistance. Secondly, high schools are nothing if not the most efficient rumor mills yet devised, and tales of the football team’s one-night-stand playoffs are out there to be heard by those who know where to listen. And of the greatest importance, Rachel works at a photo development lab. Lisa took pictures of her date with Eric (nothing porny, you understand, but still indisputable proof that the two kids were together on Lisa’s last weekend on Earth), and she gave Rachel that film to develop on the bus to school the morning of her death. The pieces are all there, waiting to be assembled, and Mark inadvertently nudges Rachel toward assembling them when he pays a visit to her workplace, and tries to buy the dead girl’s film. Eric’s position as son of the most formidable lawyer in town might shield him from the criminal case that Kelton wants to press, but he still stands to lose much from having his reputation sullied just now. He’s angling for a football scholarship from a Catholic college, and the Church tends to frown on sex scandals, when its own clergy aren’t implicated in them. Rachel could fuck Eric but good if she felt like it, and the point is by no means lost on him.

The first attempt to shut Rachel’s mouth doesn’t quite have the intended effect. Mark rounds up most of the football team (we’ll address the major exception in a moment), and brings them round to Rachel’s house one night while her foster parents are out in the hope of terrorizing her into keeping quiet. Rachel is terrorized, alright, but to all appearances, what she’s really afraid of is losing control of her uncanny power, and turning the lot of them into jockburgers. Otherwise, the only effect the incident seems to have on her is to make her briefly reconsider the unexpected romance she recently launched with Jesse Ryan (Jason London, from Dracula II: Ascension and Dracula III: Legacy), the brightest and most decent of the football players, with whom she shares an English class, and who coincidentally came to her rescue one night when her dog, Walter, was run over by a car and badly injured. Jesse might once have been both Tracy’s boyfriend and a participant in Mark’s tawdry contest, but he’s seeing the world a little differently now that Rachel is in his life— differently enough to put himself between Mark and Rachel when he finds out about the raid her house. The direct approach having been thus thwarted, Mark turns to guile instead, collaborating with Tracy and a friend of hers named Monica (Snakes on a Plane’s Rachel Blanchard) to engineer a humiliation for Rachel not too far short, in its way, of a pig’s-blood shower on the stage at prom. Meanwhile, Sue Snell has become thoroughly convinced she smells Carrie-style trouble, and when Rachel rebuffs her efforts to bond over the burned-out ruins of the old high school, she goes looking for Barbara Lang, hoping that the psychic girl’s mom can talk her into seeking help before there’s another massacre. This wouldn’t be a proper Carrie sequel if that happened, though, would it?

The Rage: Carrie 2 was released to theaters on March 12th, 1999. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold shot up Columbine High School in the unincorporated Denver, Colorado, suburb of the same name on April 20th, 1999. I point this out not to drawn some spurious connection between the two events, but to emphasize how narrowly The Rage escaped going straight into a vault, never to be seen by the public. In March of ‘99, Carrie 2 was merely a morally confused teenage revenge fantasy, something screenwriter Raphael Moreu could have extracted from the brain of virtually any adolescent malcontent in America. A month later, however, it looked disturbingly like an apologia for Harris and Klebold’s killing spree— and frankly, it still does. It’s here that Carrie 2 both becomes most inadvertently fascinating and goes most seriously astray, and it all comes down to the thoroughly misconceived characterization of Rachel Lang.

The original Carrie is a tragedy at heart, and like all good tragedies, it has a horrible inevitability about it. Carrie White had led a joyless, loveless, terrorized existence for as long as she could remember. She lived in perpetual fear of her mother, her teachers, her peers, her god, the strangers she passed every day on the street— everyone and everything, in short, that she might ever encounter. She was deliberately kept in ignorance of the world around her, systematically prevented from ever developing the skills to form a healthy relationship with a single other person, and shunned by everyone with whom she might have felt like trying anyway. The power to rain down apocalyptic paranormal violence on her persecutors was literally the only form of power she had. And crucially, those persecutors, with a couple important exceptions, were portrayed by De Palma as less consciously malicious than callously, thoughtlessly mean. Chris Hargenson might have hated Carrie on a personal level, but the other kids were just enforcing the same pecking order that they’d uncritically accepted since probably kindergarten, while the grownups at school mostly ignored the abuse because mistreating each other is simply what children do. None of these people understood the significance of the wild card that got dealt when Carrie’s belated first period hit. Except for Sue Snell and Miss Collins, they just went right on doing what they’d always done, and the efforts of those two to make a change for the better actually turned things catastrophically worse.

There’s no tragedy or inevitability in The Rage: Carrie 2, though. Here, it’s just shitty people receiving a grisly excess of comeuppance from someone who deliberately chooses to become a mass murderer, even though she has no shortage of other, more legitimate options. Indeed, the foul prank that moves Rachel to turn a post-game party at Mark’s parents’ vacation house into a reenactment of Carrie White’s prom was devised as a bid to intimidate Rachel out of pursuing those options! Mark had no interest in her at all until it became apparent that she knew enough to link Eric to Lisa’s suicide. That lack of interest is itself a big part of why the climax doesn’t work, for it’s difficult to accept Rachel as a victim finally brought to bay when she suffers so little victimization up ‘til then. Furthermore, even the one major previous incident— the football team’s visit to Rachel’s house— is less than convincing because Rachel is so obviously not cowed by it. Strong-willed, thick-skinned, occasionally hard-headed, and equipped with knowledge that could be fatal to the social standing of every jock in her high school, Rachel is simply not a credible underdog. She’d be facing Mark and his friends from a position of strength even without the psychokinesis, and what’s worse, she visibly enjoys the carnage she creates at the party, in a way that Carrie White never did. For Moreu and director Katt Shea to treat her as the heroine of this story even then is obtuse to the point of grotesquery.

It also calls attention to the gigantic laziness of this script, finally making it impossible to ignore how far out of his way Moreu went to duplicate or analogize every key beat of Carrie’s story, whether or not such duplication or analogy made any sense with respect to these characters or their situations. Rachel does what she does because it’s what Carrie did; Jesse Ryan does what he does because it’s what Tony Ross did (right down to the display of un-jock-like “sensitivity” in English class!); Mark and Tracy do what they do because Chris Hargensen and Billy Nolan did functionally equivalent things (although in their case, The Rage is at least clever enough to pull a bit of role reversal). Only Sue Snell has any good reason of her own for her behavior, and even she comes in for some “because Miss Collins did it” in the end. We got along fine for 23 years without this sorry excuse for a sequel; if all Shea and Moreu were going to do was make the same damn movie over again, only dumber, we might just as well have waited the extra three years for the made-for-TV remake.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact