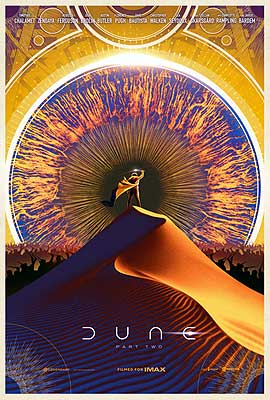

Dune, Part Two (2024) ***½

Dune, Part Two (2024) ***½

Deconstruction is supposed to be disorienting. If it isn’t, it’s either a sign that somebody’s fucking it up, or a sign that the target has already been deconstructed so thoroughly that there’s no point in doing it anymore. So I can’t give David Lynch too much grief for getting disoriented, and missing Frank Herbert’s point when he adapted Dune to the screen 40 years ago— especially since Dune is an example of the best and most challenging form of deconstruction, the kind that doesn’t let on what it’s doing until the reader is already invested in what looks like a pretty straight treatment of some very familiar tropes. I’m sure it didn’t help Lynch, either, that a lot of what Dune deconstructs— particularly the messianic Chosen One and the underdog band of Heroic Freedom Fighters— is so deeply ingrained in the American cultural imagination that some effort is needed even to conceive of taking it at something other than face value. Mind you, obtuseness in the face of Dune plainly isn’t just an American problem, because everything I’ve read about Alejandro Jodorowski’s abortive adaptation from the 70’s suggests that he missed the point even further than Lynch did. Perhaps you can understand, then, why I’ve been skeptical that Denis Villeneuve really got it, either. After all, Dune, Part One left off at a point in Frank Herbert’s narrative when it hadn’t even been hinted at yet that Underdog Chosen One Freedom Fighter protagonist Paul Atreides was a ticking time bomb whose victory over his obviously monstrous enemies could result only in carnage, destruction, chaos, and tyranny on a scale unprecedented in humanity’s already blood-soaked history. Well, now Dune, Part Two is upon us— and he gets it! Denis Villeneuve actually gets it! His version of Dune, like Frank Herbert’s own, resolves itself in the second half into a close, hard look at the mountain of bleaching skulls that seems to crop up every time anyone tries to realize the nigh-universal fantasy of the delivering hero chosen by destiny to right all wrongs and to bring perfection to a wearyingly imperfect world.

House Atreides of Caladan is no more. Their ancestral enemies, House Harkonnen of Giedi Prime, are reestablished in administration of Arrakis, in the person of the Beast Rabban (Dave Bautista again), nephew of the family patriarch, Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (a returning Stellan Skarsgård). With Duke Leto Atreides dead, and his popularity among the great nobility of the Imperium rendered permanently irrelevant, Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV (Christopher Walken, from The Addiction and The Dead Zone) is once again secure on his throne as the nominal ruler of the known universe. And the whole operation produced only a minor disruption in the production of the Spice Melange, the unique Arrakeen commodity on which long-distance space travel depends in some unspecified way. So why does Shaddam feel so naggingly certain that he’s made a terrible mistake somewhere in bringing all that about? His daughter and heiress, Princess Irulan (Florence Pugh, of Malevolent and Midsommar), can see no more reason for the emperor’s misgivings than he can, and isn’t terribly worried about them. After all, even if some unforeseen complication should suddenly arise, her father still has his ultimate political weapon— Irulan’s hand in marriage— loaded, holstered, and ready to draw at any time.

Speaking of unforeseen complications, though, a squad of Rabban’s soldiers are getting their asses kicked by one even then. Duke Leto’s teenaged son, Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet once more), survived the Harkonnen reconquest of Arrakis, together with his mother, the Bene Gesserit mystic Lady Jessica (still Rebecca Ferguson). They have been welcomed, tentatively and somewhat begrudgingly, into the tribe of Fremen— the original human colonists of Arrakis— whom the duke was courting as potential allies when Rabban permanently disrupted all his plans for the planet. Between their martial arts training and Jessica’s combination of religious authority and superhuman mental abilities, the two offworld refugees promise to make themselves valuable indeed to Stilgar (Javier Bardem again), the Fremen chieftain. And under the tutelage of a girl named Chani (still Zendaya), Paul has been adding mastery of Fremen desert survival techniques to his repertoire of useful skills. Some indication of how formidable this combination of Caladanian and Arrakeen traditions of badassery can become may be gleaned from the ease with which two kids with knives manage to slaughter half a dozen riflemen wearing levitator backpacks enabling them to leap tall mesas with a single bound.

Mind you, Paul isn’t doing all this training for his health (although the health benefits of being able to kill Harkonnen soldiers in job lots are both considerable and obvious). He wants to exact the ultimate revenge on his father’s killers by making Duke Leto’s dream of an Atreides-Fremen alliance a reality. And since the Fremen love a good fight anyway, Stilgar doesn’t require much nudging before he starts making pinprick raids against Rabban’s Spice-harvesting operation But if Paul wants to rally the Fremen against Harkonnen power per se, he’ll need to be able to do more than nudge. He’ll need to become a Fremen to the maximum extent possible, so that the army he hopes to turn loose on his enemies one day will see him as someone worthy to lead. It happens that Paul’s ambition dovetails nicely with that of his mother— who, you might recall, bore Paul in the first place as a kind of coup against the Bene Gesserit order, in the hope of hastening the arrival of the space nuns’ eugenic messiah, the Kwisatz Haderach, by a generation or two. So while Paul works his ass off to earn the Fremen’s acceptance as a warrior, Jessica exploits her religious position to encourage the tribesmen to see in him the Mahdi promised by their own prophecies— prophecies which were seeded untold centuries ago by the Bene Gesserit themselves. She takes over as the Reverend Mother for Stilgar’s tribe when their own Reverend Mother (Giusi Merli) dies, and works subtly but diligently to reshape the faith of Stilgar’s Northern people to resemble that of the Southern Hemisphere’s Fremen fundamentalists. Stilgar himself hails originally from the South, so he proves as susceptible to Jessica’s influence as he is to Paul’s.

As for the Bene Gesserit and their messiah-breeding program, that whole effort was thrown into chaos by the destruction of House Atreides— but not into unsalvageable chaos. House Harkonnen, too, was being prepped as a Kwisatz Haderach lineage, and Baron Harkonnen’s other nephew, Feyd-Rautha (Austin Butler, of The Dead Don’t Die and The Intruders), has just as much potential to father (or grandfather, or whatever) the expected god-man as the supposedly murdered Paul. Granted, Feyd-Rautha is also a batshit-insane pervert who makes his uncle look downright charming in comparison, but nobody ever said psychosis was a disqualifying factor in siring the savior of the universe. Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam (still Charlotte Rampling) sends an attractive Bene Gesserit novice named Margot Fenring (Lea Seydoux, from Zoe and Crimes of the Future) to Giedi Prime to scope out Feyd’s strengths, weaknesses, and potential levers of control.

Meanwhile, back on Arrakis, the raiding campaign against Rabban is starting to look increasingly like Paul’s longed-for war. Spice production is beginning to fall below quota as Stilgar’s tribesmen get better and better at ambushing and destroying harvesting combines, enough to be concerning not merely to Rabban, but more importantly to his uncle back home on Giedi Prime. Also, it turns out the Fremen aren’t the only ones harrying the Harkonnens, for Paul’s old drill instructor, Gurney Halleck (Josh Brolin again), has not only survived Rabban’s invasion, but has organized a cadre of fugitive Atreides soldiers into a crew of Spice pirates. Gurney and Paul are reunited when the Fremen mistake the pirates for Harkonnens, and attack them; luckily the two old friends recognize each other before either side suffers too many casualties. Their meeting is a game-changer, for Gurney has more to offer the escalating insurrection than a body of trained fighting men: he’s the only man alive who knows where Duke Leto hid the Atreides family nuclear arsenal (all the Great Houses have one) upon relocating to Arrakis. I’m sure 92 old A-bombs will come in handy somehow, right?

There are dangers in all this, though, that only Paul and Chani have so far perceived— and even they perceive them only dimly and in fragments as yet. Chani doesn’t like how dependent the struggle against the Harkonnens is becoming upon the Southern fundamentalists, and she really doesn’t like how the notion that Paul might be the Mahdi is spreading among her elders in the tribe. Paul, for his part, is having disturbing dreams in which he follows a shadowy figure into the South, which somehow results in apocalyptic suffering all across the planet— maybe all across the known universe. Chani dismisses these dreams as a side effect of Paul’s system adjusting to the Spice-rich Fremen diet, but he isn’t convinced. Long before Paul ever set foot on Arrakis, he’d had a marked propensity for prophetic dreams (he can thank his Bene Gesserit breeding for that), and that’s what his new nightmares of famine and ruin feel like. Paul knows he’s on course to make some monstrous, hideous mistake, but he can’t yet foresee what it is. And then of course there are the cosmopolitical ripples that his activities against Rabban are already casting across the universe. In the Arrakeen capital, closest at hand, the Harkonnen tyrant has concluded that the only solution to the Fremen problem is their complete extermination. On Giedi Prime, Baron Harkonnen has decided that Rabban simply lacks the competence to do what needs doing, and is prepping Feyd-Rautha to show his idiot brother what a real genocide looks like. And in both the imperial court and the Landsraad— the quasi-legislative assembly of the Great House leaders— sentiment is growing to the effect that the whole situation on Arrakis has gone so completely out of hand that no Harkonnen can be trusted any longer to restore stability.

The turning point in Dune, Part Two comes when Paul takes the Water of Life, an Arrakeen prophetic drug even more powerful than Melange, in order to understand exactly how his actions threaten to send the known universe careening into the madness of interstellar holy war. Only women are supposed to be able to withstand the Water of Life’s physiological effects, so Paul’s survival of this self-imposed ordeal is both the final proof that he is indeed the Kwisatz Haderach and the final step that makes him so. In any remotely normal Chosen One narrative, it would be the moment when Destiny is fulfilled, and indeed it was exactly that in David Lynch’s Dune. Here, though, it is instead the moment when Paul ceases to be at all recognizable as himself— the moment when he commits the very calamitous, irrevocable error that he drank the Water of Life in the hope of avoiding. As the Kwisatz Haderach, Paul no longer cares about preventing the war against the Harkonnens from blossoming into the cosmic jihad of his nightmares. He no longer cares about the liberation of his adoptive people as an end unto itself, toward which his personal revenge is but conveniently in service. Now that he can see both past and future as clearly as his hand in front of his face, he loses the uncertainty that made it possible for him to remain a moral being. In my review of Dune, Part One, I groused that Villeneuve had left the Harkonnens insufficiently developed to be the active, comprehensible villains that the movie required. I see now that that was misguided, because Villeneuve is treating Dune as a tragedy in which Paul himself becomes a villain more terrifying than any of his adversaries could ever hope to be.

Chani is the key to making all that work. Throughout the film, she represents the voice of practicality and reason, in contrast (if not necessarily in opposition) to Stilgar’s desperate thirst for eschaton. Even before Paul tells her of his troubling dreams, she urges him and anyone else who’ll listen to beware of the Southern fundamentalists and their bloodthirsty mysticism. And although she never does so overtly, she positions herself as an anchor for Paul in the real world of sand and sweat and good, sharp knives, so that he might have something to cling to against his mother’s ever-intensifying push into the realm of synthetic superstition designed for Fremen consumption by the Bene Gesserit order. And if you think back to the first film, in which Villeneuve gave Chani the scene-setting opening narration, it becomes clear that this Dune has been her story all along, for all that she’s been offstage for most of it. Hers was the subliminal protectiveness toward the outmatched and unjustly manipulated Paul that thrummed in the background of Dune, Part One. Hers is the love and admiration that burnishes his rise to the threshold of heroism in the first half of Part Two. And hers is the bitterness and betrayal that increasingly dominate the film after Paul drinks the Water of Life, surrendering to his destiny as the Kwisatz Haderach, ravager of civilization. There’s a moment early in the second act when Paul tells Chani, “I’ll love you as long as you breathe,” and she replies, “I’ll follow you as long as you’re you.” In the moment, it just sounds like the kind of pledge that any two extremely violent teenagers in love would make to each other, but it turns out to be an omen as ominous as anything served up by Paul’s Spice-enhanced subconscious.

Otherwise, Dune, Part Two is pretty much of a piece with Dune, Part One, only better. There’s still no word on how the Spice enables space travel, and that still annoys me, but in every other respect, the sequel is marked by the kinds of improvement that come with experience, reflection, and refinement. Most obviously, Villeneuve at last moves completely out of David Lynch’s shadow with regard to the look of the picture. That especially becomes apparent in the arena sequence on Giedi Prime, when Feyd-Rautha slays the last handful of Atreides prisoners taken on Arrakis in gladiatorial combat. In accordance with a rather nifty conceit that the planet orbits a “black sun” (I’m not sure whether we should take that to mean a black hole or some type of strange, cold star that that radiates the bulk of its energy at frequencies too low to stimulate the human retina), Villeneuve and cinematographer Greig Fraser used infrared-sensitive film to shoot these scenes, giving the image so genuinely unearthly a quality that it becomes physically uncomfortable to look at after a while. I’ve never seen the like of it anywhere. But even such minor details as the mechanics of Fremen sandworm-riding get new and visually distinctive interpretations, to memorable effect throughout.

Backing up again to Giedi Prime, I said before that Villeneuve’s iconoclastic take on Paul obviated the need to flesh out the Harkonnens much further than “they’re the enemy.” That doesn’t mean, however, that I’m not pleased to see this movie doing so anyway. Our first hint beyond the strange and unsettling physical appearances already established in the first film comes when the Fremen don’t bother to dehydrate the corpses of the soldiers killed by Paul and Chani, because they’re too full of toxic chemicals for any water extracted from them to be drinkable. Then we get to spend enough time with Rabban for him to emerge as an actual character, employing more of Dave Bautista’s talents than just his weird, wrinkly head. Baron Vladimir also reveals some new depths— or rather, the telling absence thereof— and if he’s been toned down and diminished in both his depravity and his political acumen relative to David Lynch’s version, or even Frank Herbert’s, there’s a deliberate reason for that, which I’ll go into shortly. But most of all, Austin Butler’s Feyd-Rautha turns out to be well worth the wait. He’s simply a magnificent antagonist for Paul, a rampaging id-monster who equals without in any way resembling the grotesquery of Lynch’s Harkonnens. I mean, the guy keeps a harem of cannibal slave-girls in his suite at the baronial palace, okay? That’s some Joel M. Reed shit right there, making up and then some for anything the Harkonnens’ portrayal in Dune, Part One was lacking.

Also well worth the wait is the belated introduction of the imperial court. Like Lynch before him, Villeneuve apparently looked to the Austro-Hungarian Empire for inspiration, but rather than raid Habsburg Vienna for styling cues, he turns Shaddam IV into a direct sci-fi analogue for Kaiser-und-König Franz Josef. Christopher Walken (who gives off some truly alarming “John Carradine in 1985” vibes— I really hope he was just acting!) plays the Emperor of the Known Universe as a doddering reactionary, clinging to senescent tyranny with a palsied grip. That’s rather at odds with the source novel, in which Shaddam, despite his immense age, was as vigorous as a man of 35 thanks the medical marvels accessible to someone of his station, but it makes good thematic sense. Few regime-types can compete with gerontocracy when it comes to sowing the seeds of their own destruction, and that’s exactly what Shaddam does with his scheme to shore up his position by taking out Duke Leto Atreides. Like his accomplice, Baron Harkonnen, the emperor thinks he’s still a peerless grandmaster of dynastic politics, but neither one of these evil old geezers has what it takes to cope with an out-of-context problem like a rogue Kwisatz Haderach leading an army of fanatics toughened to invincibility by life on the most hostile inhabited planet known to humankind. And although this is a crude bit of foreshadowing, I do like that when we meet Shaddam, he’s in the middle of losing a game of Future Chess to Princess Irulan. On the surface it’s a sign of how troubled the emperor is about the aftermath of his “victory” over the Atreides, but it’s really a portent of the self-initiated disaster headed his way. Again, Villeneuve gets this story, on a level that I hadn’t trusted anyone in the movie business to get it until now.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact