Dog Soldiers (2001/2002) ***½

Dog Soldiers (2001/2002) ***½

Some monsters lend themselves particularly well to a certain specific plot template. A dragon, for example, tends to imply a hero on a quest to slay it. A dinosaur or other creature of prehistory suggests a lost world adventure, possibly culminating with the creature brought back to civilization as an ill-advised flourish of showmanship. Hostile aliens invite some variation on the “horror from beyond” premise. Post-Romero zombies are perfect for siege tales. But just because a monster seems a natural fit for one kind of story, that doesn’t mean it can’t or shouldn’t be used in another. In fact, sometimes taking a monster out of its natural narrative environment is the most interesting way to use it. That’s what Neil Marshall did with Dog Soldiers. Traditionally, werewolf movies are about incipient dualism, as the protagonist or someone close to him progressively succumbs to an overwhelming resurgence of animal nature. Indeed, even when the werewolves are treated as an outside threat— as in The Company of Wolves or The Howling, for instance— a deadly disparity between outward and inward personality is normally that threat’s salient characteristic. Dog Soldiers is different. There is an element of traditional lycanthropic dualism in this film, but in the main, this is a siege story with hints of backwoods horror, and it takes the unusual approach of putting its besieged protagonists in a position of considerable strength. It’s just that the attacking werewolves are even stronger.

I mean seriously— if you had to be stuck with one small group of people in the event of a mass werewolf attack, you could do a lot worse than a squad of British Army infantry on covert ops maneuvers. And as if that weren’t a sufficiently winning hand by itself, one of these guys— Private Cooper (Kevin McKidd, of Hannibal Rising and Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief)— was once courted by the Special Forces, although he dropped out of the training program over what might be politely termed “philosophical differences” with his would-be mentor, a bad-news hard-ass named Captain Ryan (Liam Cunningham, from The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor and Clash of the Titans). True, the soldiers’ submachine guns are loaded with blanks, but Cooper and the rest have got the full battle kit otherwise, to say nothing of thorough training in combat tactics, unit cohesion, wilderness survival, and all the other things the queen’s army deems it proper for a fighting man to know.

Anyway, this small-scale wargame pits Sergeant Wells (Sean Pertwee, of Event Horizon and Devil’s Playground) and five grunts— the aforementioned Cooper, plus Joe (Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow’s Chris Robson), Bruce (Highlander: Endgame’s Thomas Lockyer), Terry (Leslie Simpson, from Crawlspace and Beyond the Rave), and Spoon (Darren Morfitt)— against a much larger and more powerful Special Forces team forming a perimeter around some arbitrary geographical objective in the middle of Scottish Highland nowhere. Naturally, the goal is for Wells and his men to sneak through that perimeter within a defined amount of time, preferably without having to engage the SAS unit directly at all. Or at any rate, that’s what the six ground-pounders think they’re supposed to be doing. They’ve been rather seriously misled, but it’ll be a while yet before it becomes apparent how.

Hint #1 to the unstated purpose behind the exercise is the reputation that this particular stretch of forest has in local lore, to the extent that one can speak of “local” lore in connection with so remote a place. These woods aren’t so isolated that they don’t attract the occasional camper, and rumor has it that said campers have a way of disappearing. We know the stories are true, too, because we got so see one of the disappearances in the opening scene. Let’s just say that there have to be less traumatic ways to vanish than that!

Hint #2 takes the form of a badly mangled cow carcass that comes sailing through the fucking air to land smack in the middle of the infantrymen’s campsite late on the first night of the exercise. As soon as the initial panic subsides (flying fucking cows have a way of rattling even the stoutest of nerves), Cooper observes that the animal’s wounds look more like the work of teeth and claws than of bullets and blades. That satisfies Wells that Ryan and his men aren’t about to descend upon them from the underbrush with guns pretend-blazing, but a certain amount of heightened wariness nevertheless seems in order. An animal probably wouldn’t attack as many men as Wells has under his command, but putting a second pair of eyes on overnight watch certainly wouldn’t hurt, given what this particular animal has already proven itself capable of.

The third and final hint comes to light as the result of a distress signal from Captain Ryan’s force. Shooting off flares into the predawn twilight isn’t exactly standard operating procedure for people trying not to be seen, so Wells leads the squad off to investigate. It takes most of the day to reach the SAS encampment, and when they arrive, they find the place a mire of spilled blood and extracted entrails. Ryan himself is the only one left alive, and he’s hurt pretty badly. He also isn’t making a whole lot of sense. He just keeps saying that there was supposed to be only one, unhelpfully neglecting to specify one of what. The SAS guys were much better armed than Wells and his squad, which is perhaps to be expected. It’s weird, though, that they should be carrying live ammo on a training mission, let alone such a vast profusion of it. Regardless, the sensible thing to do at this point is obviously to treat the surrounding woods as a for-real combat zone, while simultaneously calling for help. Unfortunately, the Special Forces team’s radio is smashed, and when Wells’s communications guy tries his own set, he discovers that it’s been tampered with. Near as he can tell, the only thing it’s good for now is enabling outsiders to track the squad’s movements around the forest.

That’s about when the shit hits the fan. The sun is setting by this time, and as soon as the sky is more or less fully dark, the soldiers are attacked by a pack of very large, very strong, and exceedingly fast creatures of no species that any of them recognizes. Bruce is killed almost immediately, and the sergeant severely wounded. Cooper takes charge, and manages to rally the troops sufficiently to make an organized retreat with both Wells and Ryan. The soldiers get a nasty surprise when they start fighting back in earnest, though. Bullets hurt the attacking creatures in the sense that the impacting rounds unmistakably cause them pain, but there’s no sign that the submachine guns raided from the SAS camp are inflicting any actual injury on their targets. Then, finally, comes a little stroke of luck. There’s a road through the forest, and the fleeing men reach it at the very moment when an antique Land Rover comes trundling along.

This is less of a coincidence than it might seem. Megan (Doomsday’s Emma Cleasby), the driver of the vehicle, is a field biologist, and she interrupted her work to search for the soldiers as soon as she heard the first gunshots. She also seems strangely unsurprised to see either an infantry squad on the verge of rout or a werewolf pack chasing them down like hares. That’s because Megan was supposed to be Ryan’s expert advisor on his real mission. Wells and his men, far from being Ryan’s opponents in a wargame, were actually the bait in a Military Intelligence werewolf hunt! But as Ryan himself keeps saying, he and his superiors were under the impression that there was but a single lycanthrope prowling this part of the Highlands, when in fact there are closer to half a dozen of the things. Be that as it may, the most immediate way in which Megan can make herself useful is by transporting the troops to the only house she knows of within entirely too many miles, which fortuitously belongs to some friends of hers. The place isn’t exactly a fortress, but it’s sturdy enough to be defensible, and the windows are well-positioned to serve as gun emplacements, for whatever good that’ll do. When Megan and the men reach it, though, there’s nobody home, and much evidence that the folks living there left in a big hurry. The vacancy has implications more serious than mere creepiness, as I’m sure you’ll realize if you attempt to correlate “werewolf pack” with “only house within entirely too many miles.” Another point with serious implications that have thus far sailed right over our heroes’ heads: Ryan and Wells, having been wounded by the wolf men, are in surprisingly good shape, and they seem to be getting better rather than worse.

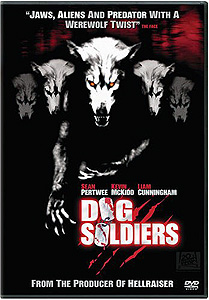

I tend to be skeptical of horror movies that comport themselves as action films instead. Partly that’s because I’m just not that fond of shoot-‘em-ups or explosion movies, but it’s also partly because I saw so many really terrible horror-action hybrids during the 1990’s. I’m very glad I overcame that distrust with regard to Dog Soldiers. Aliens and Predator are the obvious points of reference (even the DVD cover draws that parallel), and for once the comparison is not totally unfair. Dog Soldiers is clearly the lesser movie in each case, but the mere fact that it can hold its own in such august company is impressive. Naturally, the orchestration of the main set-pieces is the first key to its success, but that’s by no means the whole explanation. This movie feels taut and suspenseful throughout, despite a considerable amount of fairly leisurely downtime, principally because it puts that downtime to good use. Writer/director Marshall makes a heavy investment in character development even for figures who are, in plot terms, little more than Expendable Meat, and some indication of the return on that investment may be had from observing that I came away with a strong sense of every soldier’s personality, even though I never did manage to match names to faces for any of them except Cooper, Ryan, and the sergeant. The three major plot twists in the second half are handled superbly, in that all the information necessary to spot them is available practically from the get-go, but none of it conspicuously enough to telegraph what’s coming. Amid all the desperate chaos of the overmatched soldiers fighting for their lives, it’s easy for the viewer to become just as reactive and short-sighted as the characters. The werewolves themselves are the best I’ve seen in many a year, and to Marshall’s great credit, they were created primarily via practical effects.

Really, I have but two serious complaints with Dog Soldiers. First of all, the power level of the werewolves— their physical strength, their speed and agility, their capacity to bear the pain of 9mm bullets tearing through their regenerative flesh at the rate of thirteen rounds per second— is irritatingly variable in accordance with no visible principle beyond short-term plot convenience. And more importantly, for a movie that sets such store by the nocturnal nature of its monsters, Dog Soldiers is far too haphazard about both its day-for-night cinematography and its lighting in scenes that genuinely were shot after sunset. More often than not, it is simply impossible to tell when any given non-werewolf scene is meant to be taking place, and the presence of the creatures themselves is far too frequently the only indication that it’s supposed to be nighttime in scenes where they do appear. The problem grows worse as the endgame nears, for by then it is explicitly a race to the dawn for the few beleaguered survivors who still remain. Races to dawn don’t work very well when the audience can’t tell whether the light streaming in through the windows represents the first rays of the rising sun, or just an injudiciously cranked-up klieg lamp.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact