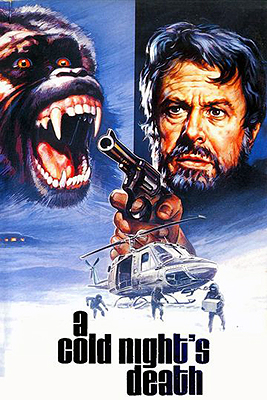

A Cold Night’s Death / The Chill Factor (1973) **½

A Cold Night’s Death / The Chill Factor (1973) **½

Some of the most difficult movies for me to rate are those that throw a rod within sight of the finish line. Even a rating system like mine, which you’d think would allow all the room for nuance that anyone could ever need, has no obviously appropriate score for something that conducts itself admirably for most of its length, only to blow it at the last moment. Is it fair to dock an otherwise exemplary film significantly for the missteps of its final minutes? Is it fair not to? A Cold Night’s Death presents an especially stark example of the conundrum, because it is literally the very last shot that does the damage. Up to then, A Cold Night’s Death had been one of the strongest 1970’s TV horror flicks, prefiguring in various ways such top-shelf classics as The Shining and The Thing. But the implications of that last shot are so poorly thought out, and so difficult to square with everything we’ve seen for the preceding 74 minutes, that I can’t give this movie anything like the recommendation that it was on track to earn.

There’s trouble up at the Summit Laboratory of the Tower Mountain Research Station. Dr. Vogel, conducting a primate study of prolonged exposure to high altitudes and restricted diets at the behest of NASA, has fallen completely silent after several weeks of increasingly incoherent and disturbing communications with his colleagues at the mountain’s foot. Toward the end, he was even exhibiting such clichéd psychotic symptoms as reporting conversations with the likes of Napoleon Bonaparte and Alexander the Great. The project is on a tight schedule, and there’s a lot riding on the results, so Vogel’s bosses are sending Robert Jones (Robert Culp, of Spectre and A Name for Evil) and Frank Enari (Eli Wallach, from Plot of Fear and The Sentinel), the top scientists of the whole operation, to relieve him, together with a fresh chimpanzee just in case Vogel has managed to kill all the apes and monkeys already on the mountaintop.

What the new guys find when helicopter pilot Val Adams (Michael C. Gwynne, from Calendar Girl Murders and The Terminal Man) drops them off is very nearly the worst-case scenario. The Summit Laboratory’s interiors look like they were sacked by the Golden Horde, the electricity is off, and the generator is all out of fuel. The building is big enough and sufficiently well insulated that temperatures within its walls are still significantly higher than they are outside, but it’s bitterly cold just the same. The lab animals are alive, but they won’t be for much longer unless drastic steps are taken at once. That isn’t the half of it, though. While Jones and Enari scramble to get the power back on, and to stabilize the condition of the animals, Adams finds Vogel, dead and frozen stiff, sitting in front of the machine in the electronics room on which he recorded his audio logs. The window is open to the frigid mountaintop air, and all the equipment in the room is thickly encrusted with ice and frost. It’s an open question whether any of the data Vogel collected during his time at the Summit Lab can even be salvaged.

Obviously Jones and Enari have a job of work ahead of them nursing the monkeys and apes back to health and getting the laboratory shipshape again, to say nothing of the research they’ve actually come to perform. Even so, they’re not so busy that Jones doesn’t have time to note the sheer oddity of the circumstances surrounding Vogel’s death. The door to the electronics room wasn’t locked, so there was nothing to keep the ill-fated scientist trapped in there until he froze. Nor, for that matter, would he have frozen in the first place if he had just shut the damn window. Adams speculated before he flew off with the corpse that Vogel might have had a stroke or a heart attack while recording his final log entry (he sounded stressed enough in his last few radio conversations with home base, after all), but the pathologist who examines the body pronounces simple freezing as the cause of death. Was it suicide, then? But suicides welcome death, and freezing is about as painless and peaceful a way to go as you could ask for. If Vogel sat in that room with the window open to kill himself, then how to account for the expression on his face, which struck Jones as one of abject terror? Even the audio logs are no help once Jones and Enari get them thawed out well enough to play. There isn’t a second of sound recorded on them anywhere— although the faint hiss on the tapes proves that they were run through the machine at some point. Either the microphone was on the fritz (although there’s certainly nothing wrong with it now), or the log tapes were all erased before it got too cold in the electronics room for the equipment to function. Enari isn’t troubled by any of that. So far as he’s concerned, Vogel was batshit insane, no further explanation needed. Jones is convinced, though, that it doesn’t add up, and it worries him in a way that he doesn’t know how to articulate.

Nobody who knows the two men well would be surprised by their respective reactions. Enari is a methodical, unintuitive thinker, inclined to take his observations at neither more nor less than face value, and a ruthless wielder of Occam’s razor. Paradoxically, he doesn’t mind not understanding something, but he hates a mystery. When faced with the unknown, Enari prefers to assume that a prosaic explanation exists, even if he personally doesn’t know what it is. Jones, on the other hand, finds mystery exhilarating— and the more challenging to his preconceptions, the better he likes it. The contrast between their turns of mind has made Jones and Enari an extremely effective professional partnership, even as it prevents them from liking each other very much. Enari contentedly does the grunt work of measuring, recording, and compiling, while Jones teases out the minutest and most abstruse implications of the data his partner harvests. Up here atop Tower Mountain, though, with no other company beyond their laboratory animals, the scientists’ divergent personalities make for a great deal of friction. That’s dangerous in an environment as hostile as this one, where even drinking water can be had only at the cost of hours of arduous, physical labor, and the machinery providing heat and electricity requires unflagging vigilance to be kept in working order. And matters are made considerably worse by the nature of the work being done at the lab, which is right up Enari’s alley, but leaves Jones with no way of occupying his restless mind. No wonder Jones keeps gnawing at the unanswered questions surrounding Vogel’s death— he’d probably go crazy inside a week if he didn’t!

Enari soon finds reason to suspect, though, that his partner is cracking up anyway. Things keep happening at the station that may seem unremarkable in themselves, but add up to a pattern that neither man likes. Lab equipment is left running when not in use, wasting precious generator fuel. Life-support systems keep getting turned off overnight, leaving the station dangerously cold or threatening the scientists’ supplies of food or water. Most suggestively, the window in the room where Vogel died won’t stay closed. Enari knows that he isn’t doing any of that stuff, so it stands to reason, so far as he’s concerned, that Jones, the only other man in the station, must be doing it instead, regardless of his protestations to the contrary. Enari even has a plausible-sounding theory to account for why Jones would behave so recklessly: to stave off incipient cabin fever, Jones is creating a mystery to be solved, piggybacking it onto his flimsy attempts to paint Vogel’s death as something more sinister than a madman’s irrational self-destruction. We know, however, that Jones really isn’t at fault— unless, of course, A Cold Night’s Death is driving hard into the realm of unreliable viewpoints. We see him discover more than his fair share of the anomalies at the Summit Laboratory, and for that matter, we also see Enari acting paranoid about him long before he’s been given any reasonable cause for suspicion. Meanwhile, Jones has a theory of his own. It hasn’t escaped his notice that the weirdness at the station has been inflicting or threatening to inflict upon the scientists exactly the same kinds of privation to which they have been subjecting the lab animals. Just like the monkeys in their cages, Jones and Enari are faced with cold, hunger, thirst, isolation, confinement, and uncleanliness, to varying degrees of actuality and potentiality. Jones therefore believes that some unseen agency is doing it to them deliberately. Who could that agency be, though, and what’s its motivation? Have Jones and Enari become the real guinea pigs in their own experiment? Are they both just losing their minds, sabotaging themselves and each other without realizing it? Or is something much weirder going on around here?

For the record, it’s Option 3. I have enough residual respect for A Cold Night’s Death not to go into specifics, but I will say that the truth, when revealed at last, makes very little sense in the context of everything leading up to it. In order to accept what we learn in the final shot, we have to believe something fantastical about something extremely mundane, but we’re given absolutely no justification for doing so. The culprits behind the scientists’ travails would require supernatural or at least paranormal powers to accomplish what they do here, but at no point are we shown any other indication that they actually possess such abilities. Nor are we offered any potential mechanism whereby the scientists’ tormentors could have acquired the talents they’d need— not even one on the level of those B-sci-fi staples, radiation, genetic engineering, and toxic waste. The ending doesn’t merely raise questions that the rest of the movie can’t answer; much worse than that, it raises questions that writer Christopher Knopf and director Jerrold Freedman don’t seem to have understood that they were raising in the first place.

That’s a shame, because they were doing so well up to then. A Cold Night’s Death is nothing short of superb so long as it’s functioning as a story of two mismatched personalities coming undone under pressure, and so long as we’re as deeply in the dark as the characters regarding what’s really behind the strange campaign of sabotage at the lab. Robert Culp and Eli Wallach do extraordinary things with a pair of roles that give them nothing to play off of but each other and a bunch of caged simians. What starts as a complicated mix of professional respect and personal dislike curdles before our eyes into mutual paranoia, fear, and loathing. Freedman exploits the unusual setting for all it’s worth in loneliness, hostility, and oppressive atmosphere. Jones and Enari have simultaneously too much and too little room, too much and too little company, to live sanely, even without considering their unseen nemesis. A Cold Night’s Death also benefits greatly from exceptionally artful cinematography by Leonard J. South, and an appropriately spare and chilly electronic score by Gil Melle. Even more than the structural and narrative parallels between their respective “exploring the ghost lab” sequences, the interaction between stark imagery and memorably peculiar music is where A Cold Night’s Death really looks forward to John Carpenter’s version of The Thing. For all its present obscurity, I would be astonished if Carpenter hadn’t seen this movie when his local ABC affiliate ran it in the winter of 1973.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time. For our final 20th-anniversary roundtable, to which this review belongs, we're looking forward instead of back, to write up some movies of types that we intend to cover more frequently in the years to come. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact