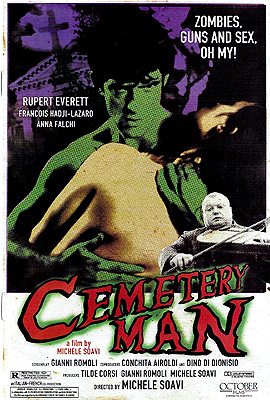

Cemetery Man / Zombie Graveyard / Demons ’95 / Dellamorte, Dellamore (1993/1996) **½

Cemetery Man / Zombie Graveyard / Demons ’95 / Dellamorte, Dellamore (1993/1996) **½

Michele Soavi didn’t set out to be Italian horror cinema’s last A-lister. For that matter, he didn’t set out to be a director in his own right at all. True, he got bitten by the filmmaking bug early, thanks to a screening of Sergio Leone’s Duck, You Sucker!, but by his own account, he was content to have just about any job in the industry. He started as an extra, and did a bit of character acting after that, but where he really seemed to find himself was as an assistant or second-unit director. His first gig in that capacity came his way in 1979, on Marco Modugno’s teens-in-trouble vanity project, Dolls. While Soavi certainly learned a few of the ropes on that project, Modugno wasn’t really cut out to be a mentor, being a year younger even than his extremely green assistant. What truly set Soavi on the road to destiny was a stint as Joe D’Amato’s sidekick, which led to a stint as Lamberto Bava’s sidekick, which ultimately brought him under the wing of Dario Argento. Soavi was Argento’s right-hand man on both Creepers and Opera, and might happily have gone on in that role indefinitely, except that both Argento and D’Amato were getting increasingly into producing during the later 1980’s. Producers need directors (unless they relish the prospect of stacking an unmanageable number of hats on their own heads), and both of the older men thought Soavi had earned a seat in the captain’s chair. Thus did Soavi make his directorial debut under D’Amato with Stage Fright before going on to helm The Church and The Sect for Argento. Finally, with Cemetery Man, Soavi turned producer/director himself, as part of a team that also included The Sect co-writer Giovanni Romoli and established movie publicist Tilde Corsi.

In terms of both international visibility and commercial success, it’s hard to argue with the position that Cemetery Man is Soavi’s magnum opus. It was something of a passion project for him, too, because it was based on a novel by comic book writer Tiziano Sclavi, who was a longtime friend of Soavi’s by the early 90’s. (That novel, Dellamorte, Dellamore, has a tangled relationship with Sclavi’s most famous creation, the long-running comic series Dylan Dog. The comic’s eponymous antihero was derived from the protagonist of the novel— at that point unpublished— with his background and profession reworked to make him more versatile as the lead in an open-ended series of tales. Then to make things even more confusing, the two versions of the character met in 1989, in a Dylan Dog story arc incorporating elements of the still-unseen Dellamorte, Dellamore!) It shows the director in impressively full command of his art and his craft, having visibly internalized the lessons learned not only from D’Amato, Bava, and Argento, but from Terry Gilliam as well, for whom Soavi had done second-unit work on The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. Its uneasy mix of horror, satire, and jet-black grossout comedy was in line with the dominant ethos of the genre’s exploitation stratum at the time of its release, while its forays into symbolic romance and its cast of arthouse darlings gave it (at least in theory) something to offer more highfalutin audiences as well. Unfortunately, it’s just a little too far up its own ass to be taken as seriously as it seems to want to be, and its expectation that we relate to and sympathize with a character who in the end is not easily distinguished from a misogynistic serial killer has aged very poorly.

In the isolated Italian town of Buffalora, behind the high stone walls of the Resurrecturis cemetery, there lives an ennui-addled young man named Francesco Dellamorte (Rupert Everett, of Merlin and the Sword and Warning). He’s the night watchman for the graveyard, and he shares his cottage on the grounds with its caretaker, a hulking, nigh-mute child-man called Gnaghi (François Hadji-Lazaro, from Brotherhood of the Wolf and Dante 01). Boneyard security is a much bigger deal in Buffalora than in most other villages, because corpses interred at Resurrecturis have a tendency to come back to life. On or about the seventh day after burial in most cases, the deceased will dig their way out of the grave with an unpredictable amount of their original intelligence and personality intact, and go looking for live humans to eat. Destroying the brains of these “returners” restores them to orderly death, and thus has Dellamorte made himself a crack shot with a high-powered revolver, and an inspired improviser with edged tools and blunt instruments. He can take down most zombies with a single round, and size up the skull-cracking potential of whatever’s in arm’s reach within seconds.

Now you might expect the curious properties of the local cemetery to be well known in a settlement the size of Buffalora, and maybe they really are. At the very least, rumors do get around. But it’s obvious at the same time that officialdom— represented by Mayor Scanarotti (Stefano Masciarelli), Dr. Veseci (Clive Riche, from Mother of Tears and The Mark), and top cop Marshal Straniero (Mickey Knox, of The 10th Victim and Frankenstein Unbound)— don’t want to know what happens at Resurrecturis after dark, and that preserving plausible deniability for those worthless worthies is as important a part of Dellamorte’s job as re-killing zombies. So even though Dellamorte’s closest friend apart from Gnaghi is the municipal clerk-archivist (The First Omen’s Anton Alexander), he can’t realistically avail himself of that connection to get the problem at the graveyard actually solved. Franco might know just the right complaint form to submit for zombie uprisings, but all Francesco would gain from filling one out is an express ticket to the unemployment line. With a future of killing monsters who used to be his neighbors stretching out indefinitely before him, and a not-so-subtle implied mandate from his paymasters in the village government to keep his mouth shut about it, is it any wonder that Dellamorte sees existence as a bleak exercise in violent futility?

But then one morning, Mrs. Martin (Anna Falchi) comes to bury her husband, Augusto (Renato Donis). Despite the dead man’s great age, his widow is young and lovely— “the most beautiful living woman I’ve ever seen,” as Francesco somewhat alarmingly puts it. Instantly smitten, Dellamorte sets about wooing the bereaved woman, in which task he is aided, on a purely practical level, by her habit of visiting the cemetery every day to put flowers on Augusto’s grave. On the other hand, Mrs. Martin’s devotion to her husband’s memory makes Francesco’s overtures a great deal less likely to land, and his complete social ineptitude doesn’t exactly help, either. Indeed, Dellamorte has just about blown it for good by the time he suddenly blunders into exactly the right thing to say: he mentions the ossuary. Nothing, it turns out, makes this girl’s motor run quite like an ossuary, and the next thing Dellamorte knows, he and the Widow Martin are going at it right beside old Augusto’s grave. She assures Francesco that that’s okay, because she and her husband always shared everything. He assumes it’s okay, too, because the old man has stayed put in his coffin for over two weeks. If Augusto were going to rise again, he ought to have done so already. But in this particular case, it seems undeath just needed a little nudge from jealousy. Augusto does indeed come out of his tomb, and he bites his widow severely before Francesco can send him back into it permanently. Mrs. Martin dies in Dellamorte’s arms (even though the watchman’s experience thus far has been that zombie bites are not lethal per se), and after a bit of finagling with Marshal Straniero and Mayor Scanarotti the next day, he’s able to get her funeral arrangements entrusted to him. You know— just in case.

To the extent that Cemetery Man has an overarching plot (which is not a great extent by any stretch of the imagination), it largely concerns Francesco’s inability to be rid of the Widow Martin once she’s dead, or indeed to make up his mind whether that’s a good thing or a bad one. Not only does the object of Dellamorte’s obsession return from the grave on two separate occasions, but she also has two separate doppelgangers among the citizens of Buffalora. Meanwhile, Gnaghi falls improbably into his own trans-mortem romance with no less unlikely a paramour than Scanarotti’s adolescent daughter, Valentina (Hi-Death’s Fabiana Formica). The girl is alive when Gnaghi becomes besotted with her, but is killed when her dirtbag boyfriend, Claudio (Allessandro Zomattio), crashes his motorbike into a school bus full of Boy Scouts. Once Valentina— or her severed head, anyway— is resurrected, however, she plausibly concludes that Gnaghi is more in her league, all things considered. Besides, Claudio had a girl on the side (Katja Anton), and she’s so determined to keep him that she’s positively thrilled over the prospect of her guy reawakening as an anthropophagous zombie.

Those threads account for the Dellamore half of this movie’s Italian title. The Dellamorte part comes to the fore when Francesco, after a contentious conversation with the Grim Reaper, begins living up to his surname by dispatching the living alongside the undead. His first couple murders are more manslaughters, strictly speaking: he doesn’t realize that the Widow Martin was merely in a cataleptic trance the first time he sends her back to the grave, nor does he intend for Claudio’s other girl to catch a bullet fragment from the exit wound when he blows the zombie biker’s head off. The rest of Claudio’s gang, though, who seem to have originated the rumor current throughout Buffalora that Francesco is not merely impotent, but literally dickless? The prostitute who looks exactly like Mrs. Martin, and her two fellow businesswomen? Those folks he kills fully on purpose, even if he seems to be in a dissociative state throughout the shooting spree against the gang. Francesco also knows what he’s doing when he kills Franco for “stealing” his crimes after the latter man goes berserk, slaughters his family, and confesses to all the recent murders before turning the gun on himself. And he knows what he’s doing when he blows away the three members of the hospital staff who successively barge in while the two old friends are having it out. But while Dellamorte may have mens rea for his increasingly offhand crimes, what he does not have is a motive that he can coherently explain, despite his incessant attempts to do so via voiceover narration. It’s just that he no longer sees any difference between the walking dead, whom he gets paid to destroy, and the naturally animate people all around him, whom he assumes to be as dead inside as he feels.

Ultimately, I think I just plain came to Cemetery Man too late in life. I’m pretty sure I would have loved this movie had I seen it in the late 1990’s, when I was a young malcontent navigating a world that seemed to have given up believing in anything, because everything worth believing in had been discredited. It’s a mindset not too dissimilar to Francesco Dellamorte’s, when you get right down to it, and no doubt it would lend me more patience for the zombie-slayer’s gloomy internal speechifying than I’m able to muster today if I still held it. Similarly, at a stage of life when every day is a battle against subconscious solipsism anyway, Soavi’s treatment of all the other characters save Gnaghi (oddly enough) as philosophical props with no interiority of their own would likely feel much less grating. But while I can no longer find Dellamorte relatable, or frankly even excusable, I do find him somewhat interesting as the perfect personification of the nihilistic streak that runs through all of Italian exploitation cinema from the Spaghetti Westerns on. He’s a purer and weirder distillation of previous Italo-schlock antiheroes ranging from Django and Sartana, through Bart Fargo and Diabolik, to all the total creeps trying not to get stabbed or strangled by giallo killers and the bastards with badges serving the cause of order (albeit certainly not law) in the polizioteschi. Dellamorte arguably has even older antecedents, too, if you expand your search into more reputable places. For starters, consider Dante Alighieri’s fictional alter ego, sadsacking his way through Hell, and taking consolation from seeing all his old enemies there.

All that said, one aspect of Cemetery Man that I haven’t aged out of at all is its sense of humor. It’s by far the Gen-Xiest thing about this extremely Gen-Xy movie (which is a curious point in itself, since Soavi and Sclavi were both born in the 1950’s), a warped admixture of wantonly cruel gallows humor, button-pushing grossout gags, and authority-baiting satire, which flirts constantly with dark absurdism in all three modes. Like it isn’t enough to have Claudio knock a busload of Scouts off the side of a mountain; Francesco and Gnaghi need to spend an evening a week or so later fending off a besieging horde of diminutive, uniformed zombies as a result. Gnaghi doesn’t just have a love affair with a reanimated corpse; he has a nauseatingly sweet and innocent love affair with a reanimated severed head. The mayor of Buffalora isn’t just a glad-handing asshole and a tinpot tyrant; he’s a glad-handing asshole and a tinpot tyrant who views even the gruesome death of his daughter as a potential tool to swing votes in his next reelection campaign. These were my kind of jokes in the 90’s, and they remain my kind of jokes even now. For that matter, the mere fact of including them in this film while simultaneously running the horror at full throttle aligns with my taste in ways that Cemetery Man as a whole mostly doesn’t anymore. Simply put, it shows the commendable influence of Evil Dead II, but not the baleful influence of Army of Darkness.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact