Carnival Magic (1981) -*½

Carnival Magic (1981) -*½

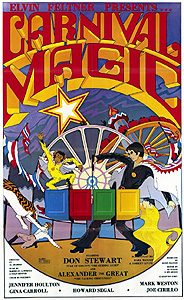

I had never heard of Carnival Magic when it popped up in the Turner Classic Movies schedule, paired with Berserk on “TCM Underground.” The description in the schedule sounded neat, though— something about a sideshow magician with real psychic powers and an uncanny bond with a freakishly intelligent ape. Immediately, I imagined something like a cross between Devil Doll and Link— which could be pretty cool, right? Sure. But it turns out that’s not what Carnival Magic is at all. Believe it or not, it’s actually more like E.T.: The Extraterrestrial, only with a bunch of mostly middle-aged carnies instead of a depressed little boy and his family, and an inexplicable talking chimp instead of a castaway alien. Oh— and it was directed by Al Adamson, during the little-known final phase of his career, when he attempted to reinvent himself as a purveyor of family entertainment. I missed that little detail in the TCM schedule, but I’m so far gone at this point that I doubt it would have deterred me if I’d noticed.

The Stoney Martin Carnival is in a bad way. Sure, it’s arguably the most exciting thing there is to do in this benighted stretch of rural South Carolina nowhere, but just look at the place. The rides are clunky and antiquated, the games are the same cheesy rip-offs you see at every attraction of its kind, and the sideshow performers are particularly weak: one lousy dwarf, a stilt-walker, a couple of listless hoochie-coochie girls, and a magician so small-time that his cheesecake assistant is the broken-down wreck of Regina Carrol (whom Adamson cast in most of his movies, including Brain of Blood and Doctor Dracula). The closest thing the carnival has to a major act is Kirk the animal trainer (Joe Cirillo, who spent most of his career playing bit-part policemen in movies ranging from Splash to Maniac Cop 2), a drunken, snake-mean egotist whose personal shortcomings are tolerable under the circumstances because he sure does have a way with tigers. Still, Stoney himself (Mark Weston) prefers to believe that insufficient publicity is his problem, so he’s hired a young guy named David (Howard Segal)— a restless refugee from the world of corporate advertising— to be his new PR man. David’s efforts so far have been largely unavailing.

Stoney’s troubles are about to multiply, too. Like I said, Kirk has a way with tigers, but that magician— Markov the Magnificent (Future Zone’s David Stewart), he calls himself— has an even better one. Forget about whips and cane-framed chairs; Markov can just talk to the cats, and to all appearances, they listen to him. Markov keeps to himself about this if he can at all manage it, but he was raised in India by Buddhist monks who taught him all kinds of neat mental tricks, including hypnosis, levitation, and various body-maximization techniques in addition to interspecies telepathy. The problem is, every time Kirk’s tigers listen to Markov, they seem to grow a little more reluctant to listen to Kirk. There’s plainly some professional jealousy involved, too, but Kirk does have a legitimate gripe here. Eventually, the trainer goes to Stoney with an ultimatum: either Markov goes, or Kirk does. Martin tries at first to talk Kirk down, since a feud between his two highest-paid performers can’t possibly bring him or his carnival anything but grief, but the tiger-tamer is adamant. Stoney gives in, and trudges over to Markov’s trailer to give him the bad news.

This is where we learn something curious about the magician. He never lets anyone inside his trailer, and speculation is rife among the carnival staff regarding what exactly he’s hiding in there. Even now that he’s being forced out, Markov won’t reveal his secret to Stoney, but Martin’s daughter, Ellen (Jennifer Houlton)— call her “Buddy,” though— will soon be finding out by complete accident. On what’s supposed to be Markov’s last day with the carnival, Buddy falls asleep after closing time in the big pavilion where Kirk and the magician perform, and the latter man doesn’t realize she’s in there when he pokes his head inside during a final late-night ramble around the carnival grounds. Thus it is that Buddy meets Markov’s chimp, Alex, whom he always lets out for a walk after everyone else has gone to bed. No, wait— let’s try that again: Buddy meets Markov’s talking, clothes-wearing, breakfast-making, car-driving chimp, Alex. Yeah, that better conveys the significance of what happens here. Suddenly, the prospects for the Stoney Martin Carnival look very different. Kirk has his selling points and all, but a talking chimp?!?! And a talking chimp who knows how to assist a magic act, no less? Alex could be the solution to all the carnival’s problems! Markov takes some convincing, though. Alex has been his sole companion ever since the accidental death of his wife many years ago, and Markov frankly isn’t sure he’s ready to share him with the rest of the world. Besides, the magician knows well how unusual Alex is, and he has a sneaking suspicion that not all the attention the ape drew would be benign if other people knew about him. In the end, he leaves the decision up to Alex himself, and the ape thinks being a star sounds like a lot more fun than hiding in his human’s trailer all the damn time. Stoney naturally seconds his daughter’s assessment of Alex’s potential, so Kirk can go fuck himself if he still refuses to work with Markov. Kirk, perhaps surprisingly, elects not to go fuck himself.

Carnival Magic is largely plotless from there until right before the end. Mostly, it just alternates Markov and Alex’s performances with static, talky scenes of the various characters working through their respective emotional wounds. Markov and his eye candy discuss his lingering feelings for his dead wife. David talks with Markov about his difficulty connecting with Buddy, and then connects with her at least well enough to talk to her about the frustrations of his former life as a nine-to-fiver in his dad’s advertising firm. Buddy gripes to anyone who’ll listen about her father’s refusal to let her grow up and be her own person. Stoney confesses to Markov the reason for his clinging, and airs both his festering grievances over the way Buddy’s mother left him to escape from the carnie lifestyle and his fears that Ellen will do the same now that she’s of age to. And Kirk bitches to his girlfriend, Kim (Diane Kettering), about how Markov and that fucking chimp have taken the spotlight away from him. That last part is our in-route to the rather stunted third act, because Kirk’s grudge neatly intersects with the agenda of Dr. Poole (Charles Reynolds), the cartoonishly evil scientist who runs the Anthropological Research Institute. Poole happens to visit the carnival one day, and he’s amazed at what he sees Alex do. Naturally, the scientist wants to study the incredible ape, and he gets decidedly snippy when Markov refuses to lend Alex out. Observing the tense conversation between Markov and Poole gives Kirk the idea that the Anthropological Research Institute holds the secret to regaining his old position as the carnival’s top banana.

Among the few really interesting things about Carnival Magic is that this story of a magical little creature who turns a lot of unhappy people’s lives just upside down enough to fix them while avoiding vivisection by only the narrowest of margins cannot possibly have been inspired by E.T., no matter how strong the plot-point-by-plot-point resemblance. Incredible though it may seem, Al Adamson’s movie came first (although E.T. must have been in some stage of production when Carnival Magic got underway), and its similarities to the Spielberg film are of a sort that can be accounted for only by either coincidence or insider information. Adamson surely had no access to the latter (and if he had, don’t you think he’d have stolen the part where the movie’s about an alien, too?), so we must be looking at a case of the former. But coincidental or not, the commonalities will be important to provide context and perspective should you ever watch Carnival Magic for yourself. You’ll need both of those things, too, because otherwise it’ll be very hard to disentangle the weirdness that Adamson personally brings to the project from the weirdness that comes naturally with the shifting of cultural mores. The echoes of E.T. will remind you how much darker the average kiddie flick was permitted to be even as recently as the early 80’s.

Heaven knows it’s difficult to imagine a movie like Carnival Magic being made for today’s juvenile audience. Beyond the vivisection lab at the end, there’s Kirk’s drunkenness and domestic violence, Regina Carrol’s skimpy yet woefully unflattering costumes, and an unconvincing but fairly explicit gore scene when one of Kirk’s tigers finally decides that it’s had enough of his shit. Carnival Magic is unusual among children’s movies for featuring not a single child among the cast, and for spending so much of its time on adult angst that kids are unlikely to understand and virtually certain to find boring. It also plays up the difference between its era’s assumptions and today’s with a scene that more or less explicitly acknowledges children as the secret target audience for car-chase movies like Smokey and the Bandit. About the one item in Carnival Magic’s repertoire that still remains a standard kiddie-flick feature is the inclusion of something that’s supposed to be cute, but is inadvertently nightmarish instead. I’m talking, of course, about Alex. That Trudi the chimp is far and away the best actor in the movie is disturbing enough all by itself. Then somebody had the bright idea to put clothes on her— not just those ape diapers you see sometimes on chimpanzees in the entertainment business, either, nor even some wacky cartoon animal costume, but ordinary street clothes such as any schlubby rural Southerner might have worn in 1981. Still not satisfied, they also trimmed her fur until she was only a little bit hairier than a full-blooded Greek or Italian man. Worst of all, Trudi’s trainers seem not to have resorted to the usual ploy of wiping peanut butter all over her gums to make her “talk.” Trudi’s mouth movements are very subtle and precise, tailored with uncanny specificity to Alex’s dialogue. I have no idea what method was used in the ape’s training, but the result completes an effect that’s positively eerie.

Otherwise, Carnival Magic is basically just dull. The one respect in which it does remind me of Berserk is its creators’ utterly mistaken belief that anyone wanted to see third-rate circus acts performed in their entirety on film. Even the conceit that Markov’s “magic” is real in a sense, the product of his upbringing in the mystical Orient, is no help in the end, because nothing ever comes of it. The police chase that ensues when Alex steals a carnival hand’s car to go joyriding is limp and uninteresting, not least because the production couldn’t afford to wreck anything but the ubiquitous wooden fruit cart. And oh my God, the jibber-jabber! So much pointless, time-spinning jibber-jabber! There is simply no respite from boredom in this movie, from the minute Markov takes the stage with Alex for the first time until Kirk goes AWOL and sells the ape to Dr. Poole. The sheer strangeness of Al Adamson trying to muscle in on Walt Disney’s racket has its allure, I guess, but only the truly battle-hardened should allow themselves to yield to whatever temptation that offers. Just be glad the sequel touted in the closing credits (“So long for now— see you next year in More Carnival Magic”) turned out to be an empty threat.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact