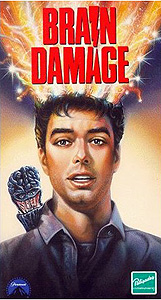

Brain Damage (1987) ***½

Brain Damage (1987) ***½

It took Frank Henenlotter a long time to follow up Basket Case, so it’s a bit surprising that Brain Damage, his second film to see release, should proceed from the same basic idea of a symbiotic relationship between a boy in New York and a disgusting little monster. But despite the similarities, Brain Damage is a much richer film, thematically speaking, than its predecessor. Whereas Basket Case was a basically unassuming, to-the-point horror flick, Brain Damage places equal emphasis on twisted humor, and could fairly be described as a message movie, too.

We begin with middle-aged New Yorkers Morris (Theo Barnes) and Martha (Lucille Saint-Peter). Morris has just come home from a trip to the butcher shop, where he went to pick up some strange groceries indeed. It’s hard to say just yet what he and his wife plan on feeding all those pig brains to, but I just bet it would go some way toward explaining the vast proliferation of locks on the door if we knew— five separate deadbolts seems excessive, even for New York. We don’t get to see the intended eater of the brains, though, because whatever it is has left its accustomed place in Morris and Martha’s bathtub, and has apparently escaped from the apartment. They turn the place over in a frantically thorough manner, but no sign of the missing brain-eater turns up. Nor is it in the bathtubs of the several neighbors they brusquely intrude upon after scouring their own place, and as we take our leave of Morris and Martha, the two of them have collapsed in a twitching, frothing heap on their living room floor.

Meanwhile, in another unit of the same apartment block, a boy named Brian (Rick Hearst, from Warlock III: The End of Innocence) isn’t feeling very well. He was supposed to go out with his girlfriend, Barbara (Jennifer Lowry), tonight, but he just isn’t up to it. In fact, Brian doesn’t even trust himself to stand up at this point. But rather than ruin Barbara’s evening completely, he sends her out in company with Mike (Gordon MacDonald), his brother and roommate. Brian himself spends most of the evening sleeping, occasionally having what look at first glance like fever dreams. But at one point, he wakes up and finds the pillow upon which he had laid his head smeared with blood— apparently his own. Brian rushes (or comes as close to rushing as his condition will allow) to the bathroom, where an inventive employment of two mirrors reveals that something has gone and poked a big-ass hole in the back of his neck, at right about the point where his spinal cord passes through the foramen magnum into his skull. Shortly thereafter, he finds the thing that made that hole, a slug-like creature about sixteen inches long, which speaks to Brian in the well-mannered voice of 50’s TV horror host John Zacherle! The creature explains that it was also responsible for the strangely ecstatic dreams Brian had earlier in the evening, and that it is able to induce more like them any time Brian wants, even if he’s wide awake. Brian has begun a new life, the creature tells him, a new life of wonder and joy and excitement, potentially free from all pain and suffering. Then it injects Brian with another dose of its hallucinogenic secretions, and suggests that it and the boy take a little walk.

As any hardcore dope-fiend will tell you, every high comes at a price. And those of you who have made the connection that this creature is what escaped from Morris and Martha’s flat probably have some idea what the price might be in this case. Brian’s walk takes him and his new symbiont to an auto graveyard, where Brian jumps the fence to get a closer look at the wrecked cars, whose complex structures make for an especially exciting visual experience under the influence of the creature’s drug. Brian’s hooting and hollering brings the night watchman, and the slug-thing attacks and kills him in order to suck out his brain. Brian will remember none of this when he wakes up the following morning.

He does remember the creature, though, and over the course of the next several days, he causes ever-escalating worry on the part of Mike and Barbara, neither of whom has a clue what to make of it when Brian refuses to leave his room except to lock himself in the bathroom for far longer than even the most luxurious bath or the most furious masturbation could plausibly account for. And speaking of locks, Brian has outfitted both bedroom and bathroom in much the same way as the front door to Morris and Martha’s apartment. Needless to say, Brian won’t say word one to either Mike or Barbara by way of explanation. Eventually, Barbara does succeed in coaxing him out for a dinner date, at which point she takes advantage of the situation to press him for answers. What little she gets out of him before he flees the restaurant (prompted by a vivid hallucination in which the meatballs on his plate of pasta seem to turn into miniature, throbbing human brains) sounds distinctly like the ranting of a drug addict, but Brian swears to her that what has happened to him is nothing so simple as taking up dope. That reassurance carries little weight with Barbara, however.

She’d be even more freaked if she could see what Brian does after he runs out on their date. His brain addled by the creature’s secretions, Brian heads over to a rock club called Hell, where he picks up a girl. But when she takes him up onto the roof to have sex, she too falls victim to the brain-sucking slug. This time, though, Brian has conclusive evidence that he was involved in something horrible during his missing hours, because the monster had been hiding in his pants when it attacked the barfly, leaving Brian’s underwear soaked with the girl’s blood. Not only that, while he’s out in the alley disposing of his sodden drawers, Brian has a run-in with Morris, who understandably recognizes the signs of the boy’s involvement with the creature. Morris details the history of the thing— which, he informs Brian, is called “the Aylmer”— beginning in 1203, when the creature was stolen from the Emperor Alexius after the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople. (Incidentally, the sack of Constantinople happened in 1204, although Alexius V was indeed the Byzantine emperor at the time.) Brian refuses to hand over the Aylmer, but Morris’s story does get him thinking. At the earliest opportunity, Brian forces the creature to tell him what’s really going on, and once he knows, he’s at least as horrified as his brother and girlfriend. Morris knew what he was talking about, and it turns out that the Aylmer’s escape was prompted by its most recent owners’ efforts to keep it weak and controllable by feeding it only animal brains, rather than the human brains that are its preferred form of nourishment. Realizing now what he’s gotten himself into, Brian packs up a suitcase and gets himself a room at a flea-pit hotel, where he figures he’ll be able to kick his habit in peace. Of course, anybody who’s ever known a junkie would be able to tell him how rarely anyone succeeds in quitting a habit-forming drug cold turkey.

You know, if the Partnership for a Drug-Free America were half as hip as it likes to think it is, it would sponsor screenings of Brain Damage in high schools across the country. It’s funny and gross and irreverent enough to endear itself to the most self-consciously cool teenager, but at the same time, it really drives home the risks of drug addiction without ever resorting to the usual platitudinous preaching. By framing the story of Brian’s descent into addiction and self-destruction in totally fictitious terms, Henenlotter sidesteps the greatest pitfall of the anti-drug movie, the tendency to sacrifice credibility by exaggerating the negative effects of a real drug to levels that any actual user will recognize as unrealistic and alarmist. But the secretions with which the Aylmer injects Brian mirror the effects of enough real-world intoxicants that any druggie watching Brain Damage will be faced with something they recognize— the Aylmer’s secretions produce sensory effects similar to LSD, cocaine-like hyperactivity, and a rush of euphoria similar to that of heroin. The withdrawal symptoms which defeat Brian’s efforts to clean himself up are also similar to those of heroin, though they resemble barbiturate withdrawal as well, especially in terms of severity. Meanwhile, I think it was a minor stroke of genius to play the Aylmer almost as a parody of the smooth-talking pusher from all those drug-panic movies of yesteryear; doing it that way lets the audience know that Henenlotter understands that they’re smarter than movies like The Cocaine Fiends and Narcotics: Pit of Despair gave them credit for. The other smart move Henenlotter made (assuming that an anti-drug polemic really was at least part of his aim) was depicting the destruction the Aylmer wreaks in Brian’s life as falling harder on those he cares about than on Brian himself. Doing so short-circuits the usual “hey, I’m only hurting myself” defense in a way that is very difficult to argue with.

But beyond all that, Brain Damage is just an infectiously fun movie, and one which makes for a very smooth progression from the off-kilter straight-up horror of Basket Case to the full-bore black comedy of Henenlotter’s later Frankenhooker. Henenlotter actually had something like a budget this time around, and the look of the film is far more professional than that of Basket Case. Nevertheless, Brain Damage sacrifices only a little of its predecessor’s uncompromising grindhouse flavor. The acting is still rather weak by pro standards, but it definitely represents a step up from what the director had been willing to accept before. Its numerous inside jokes are nicely low-key, rather than drawing attention to themselves in the manner to which I have become accustomed. (I especially like Kevin Van Hentenryk’s cameo as Duane Bradley, who takes a seat on the subway, basket in hand, right across the aisle from Brian and Barbara.) The only thing really holding Brain Damage back is the recycling of so many story elements from Basket Case, which robs the movie of some of the freshness it ought to have had.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact