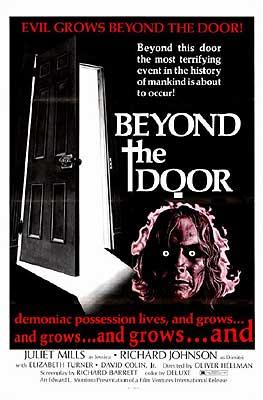

Beyond the Door / The Devil Within Her / Who Are You? / Chi Sei? (1974) ***Ĺ

Beyond the Door / The Devil Within Her / Who Are You? / Chi Sei? (1974) ***Ĺ

Taste being the idiosyncratic matter that it is, itís inevitable that every critic will sooner or later wind up in stark disagreement with a consensus so broad as to border on the universal. It happens to me rather a lot, actually, but this time is a little different. Usually, I find myself in disdain of a movie that is widely loved, and at least part of my dissent from conventional opinion can be explained as a child of the 70ís and 80ís reacting to the relative squeamishness of earlier eras. But Beyond the Door puts me in the opposite position. So far as I can see, it has no cheering section whatsoever, not even among the most dedicated delvers into cinematic disrepute, and I canít for the life of me understand why. It seems to me easily the best of the Italian Exorcist copies, and not merely to an extent that damns with faint praise. In a subgenre normally devoted to slavishly checking all the formula boxes, and maybe adding a dash of nudity here and there, Beyond the Door sets itself instead to turning its model upside down and inside out. And whereas most Spaghetti Exorcists strive to be as crassly earthy as possible, this movie plays like a half-remembered bad dream that is all the more disconcerting for almost making sense.

Ten years or more ago (time is one of the slipperiest things in this extremely slippery movie), Jessica Barrett (Juliet Mills, of Demon, Demon and Waxwork II: Lost in Time) was acolyte and lover to a charismatic Satanist guru called Dimitri (Richard Johnson, from The Night Child and The Great Alligator). It was a passing phase in her personal development, and now Jessica is bringing the countercultural sensibilities that once led her to Satanism to the venerable profession of housewifery instead. She still lives in San Francisco, but cults and communes have given way to a music-producer husband named Robert (Gabriele Lavia, of Evil Senses and Deep Red) and a pair of children. The Barretts, as you might expect with their backgrounds, are the kind of parents who have their kids call them by first name, and Iím sure the grandparents are all horrified by the results of their determinedly lax child-rearing. Elevenish Gail (Barbara Fiorini) is obsessed with the novel Love Story (she owns at least a dozen copies, and is never without one of them in easy reach), cultivates an impressively foul mouth for her age, and delights in the morbid and grotesque. Sheís also made an art form of sassing back, although she hasnít quite mastered the counterculture slang that is her preferred delivery system for it. Her little brother, Ken (Shockís David Colin Jr.), isnít so elaborately ill-behaved, although Gail is pushing him to up his game there. For now, the boyís main eccentricity is an addiction to Campbellís pea soup. (This is one of several broad inside jokes that hover uneasily over what is generally a serious film.) As we rejoin Jessica, she has just discovered that sheís going to be spawning yet a third little monster. Her and Robertís dominant reaction is neither joy nor dismay, but simple puzzlement. Jessica takes her birth control pills scrupulously every day, so this pregnancy ought to be impossible.

Dimitri could explain it to her, if they were still in contact. Evidently the Devil had big plans for Jessica while she was part of Dimitriís cult, and was displeased when she left it and moved on with her life. The pregnancy is Satanís way of winning her back, and itís Dimitriís job to make sure it comes to term. If he succeeds, Lucifer might even grant him an extension on an earlier bargain. You see, not long after he and Jessica parted ways, Dimitri suffered what certainly ought to have been a fatal car accident. The Devil granted him a further ten years of life, and now he leads Dimitri to believe that Jessicaís child, if born according to plan, will become the next vessel for his soul. Dimitriís decade is up in just a few months, so one assumes that the Devil envisions a rather expedited gestation if the handover is to work properly.

Expedited is right. Jessicaís doctor, George Staton (Nino Segurini, from Cave of the Sharks and No Manís Island), makes the disquieting revelation that the fetus shows a developmental level consistent with some three and a half months, even though itís been only seven weeks since Jessicaís last period. The pregnancy is abnormal in other ways, too. Jessica never had morning sickness half this severe when she was carrying Gail or Ken, and her mood swings this time around are downright scary. Her accustomed unflappable toleration for Gailís obnoxiousness vanishes overnight, leaving Jessica prone to fits of violent anger and simmering resentment. Nor is Gail the only target of her newfound venom. One afternoon, she smashes her husbandís beloved goldfish tank in a totally unprovoked fury. And the next time she goes to see Staton, she begins the visit by all but pleading for an abortion, and ends it by vowing to kill anyone who interferes with her pregnancy.

Even thatís only the beginning, of course. A day or two later, while Robert is out of the house overseeing a recording session or whatever, the kids are subjected to a poltergeist attack, and Mom implicitly reveals herself as the source of the supernatural disturbances when Gail comes to enlist her aid against the animate toys, flashing lights, and shaking bedroom. The Barretts wonít be seeing Jessica normal for a good long while, either. She speaks in strange voices, adopts a variety of personalities, physically attacks anyone who comes within armís reach until Robert is forced to keep her strapped down to her bed in a heavy-duty straitjacket. Staton can find nothing organically wrong with Jessica even so, save presumably the bedsore-like lesions that mysteriously break out all over her face. There is, however, one person who claims to know whatís going on here. As Robert grows increasingly desperate for answers, Dimitrió who has been lurking at the limits of peopleís peripheral vision all movie longó finally comes forward to tell him that itís all about the baby. Jessica will be fine as soon as her latest child is out of her, but it is imperative just the same that the malignant pregnancy be allowed to run its course. Then Dimitri willÖ well, he doesnít really say. Probably because doing so would make him look like an even bigger loon than he already does. Still, Robert decides that Jessica is in good hands with this weirdo out of her past, which is perhaps understandable given the pronounced lack of alternatives before him. One does have to ask, though, why Dimitri is so trusting. After all, heís got nothing to go on but a ďmaybe I will, and maybe I wonítĒ offer from a being whoís been nicknamed the Prince of LiesÖ

The relationship between parent and child can never be truly reciprocal. Consequently, in any story where that relationship matters, it makes all the difference in the world whether things are happening to one or the other. Make an Exorcist clone in which the mother is possessed by the Devil, and youíre telling a completely different story, no matter how many of the details (levitation, telekinesis, neck-twisting, appalling vomit) you carry over. Compare The Exorcistís 180-degree neck-twist scene to Beyond the Doorís, and youíll see at once what Iím talking about. Leave aside for now the rather startling point that this version hides its seams better, and is therefore more successful as a special effect. Concentrate instead on the power dynamics at work in the parallel sequences. For Chris McNeil, that first unambiguous display of supernatural malevolence from her daughter is the ultimate loss of power, both insofar as it puts Reganís behavior beyond any plausible expectation of parental control and in the sense that seeing Regan defy the constraints of her own anatomy like that demonstrates as nothing else has that Chris is simply unable in any way to protect the child from whatís happening to her. But in Beyond the Door, itís more like a betrayal of filial trust and an abdication of parental responsibility. Gail comes to Jessica after escaping from the childrenís poltergeist-stricken bedroom, needing her mother to help her save Ken from the continuing ordeal. And when she finds her mom, she finds also the monster responsible for the poltergeist activity in the first place. Then in case weíd missed the point, the following scene drives it all the way home. When Robert returns, Gail gets him alone at the first opportunity and pleads, ďPapa! Donít leave Ken and me alone with Mommy again!Ē Hereís how rattled the poor kid is: for once, itís ďPapaĒ and ďMommyĒ instead of ďRobertĒ and ďJessica.Ē Each of these scenes represents the first time a loved one has witnessed something irrefutably demoniacal on the part of the possessed; each one comes as the follow-up to a telekinetic temper tantrum; and in each one, mother and daughter are alone together when it happens. Yet the two scenes could not be any more different.

The side-by-side comparison works out that way pretty much all around. The Father Merrin figure in Beyond the Door is evil, and seeks not to expel the demon from Jessica, but to mollify it so that it will allow him to go on cheating death for another lifetime. Robert is eager to believe Dimitriís lies about being able to help Jessica, whereas Chris is reluctant in the extreme to enlist the aid of the priests who ultimately succeed in freeing Regan from Pazuzu. And most of all, there never is an exorcism in Beyond the Door, although both movies come to a head with an outsider to the beleaguered family locked away with the possessed and struggling with the being inside her. The showdown between Dimitri and the Devil is all about the latter having a good laugh at the formerís expense, which in turn makes Jessicaís possession an entirely different affair from Reganís for all their common symptomology. Far from seeking to gain new souls for Hell by breaking the faith of bystanders, this Satan is just being a straight-up dick to somebody he already owns free and clear.

The greatest strength of Beyond the Door, however, is that it doesnít overreach itself. In most Spaghetti Exorcists, every lira that the producers didnít have is right there on the screen, playing havoc with the good ideas and making unmitigated disasters of the bad ones. Beyond the Door may be as cheap as many (and cheaper than a few), but it hides its limitations very well. Naturally, the special effects are where you seeó or, more accurately, donít seeó the result most clearly. It is surely no accident that Beyond the Door steers clear of the expensive new effects technologies that were revolutionizing horror and sci-fi movies in the mid-1970ís, relying instead on techniques that Georges MťliŤs would have recognized. This film also benefits from some of the best sound design Iíve ever encountered, which is a tremendous asset in scenes like the opening Satanic ritual. Left to its own devices, that shot of the nude womanís head becoming that of a bearded and wild-looking man as she writhes on the altar in front of Jessica could be either disturbing or laughable, even with the matte effect done as well as it is here. The distorted wheezing and grunting on the soundtrack pushes it decidedly toward the former, however. The same goes for the minutes just before Gail and Ken are attacked by their bedroom. There the suspect visual component is all the childrenís toys moving about the room, while the audio accompaniment that renders it sublimely eerie is the two kidsí voices, conversing in apparent obliviousness to the behavior of their dolls and stuffed animalsó ironic, since it is precisely the secret lives of toys that the children are discussing. The latter sequence is as scary as anything in The Exorcist, and the subsequent ďrunning to tell MomĒ bit is actually scarier. (And again with those electronically filtered groansÖ) Initial reception was much kinder to Beyond the Door than historical reflection has been, to the extent that it sold nearly as many tickets as The Exorcist in some markets. Initial reception was right for once.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact