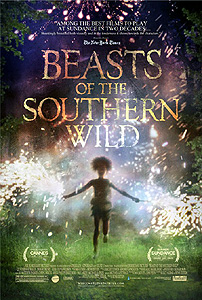

Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) ****

Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012) ****

It took me a while to decide whether I ought to review Beasts of the Southern Wild. This is very much a “sort of” movie, which doesn’t fit neatly into any of the usual boxes. It’s sort of a fantasy film in the critically acceptable style known as magic realism (think Beloved, Powder, arguably Pan’s Labyrinth), which would put it on one of the outermost frontier zones of my area of coverage. It’s also sort of a thoughtful post-apocalypse survival story, a bit like if The Road were merely melancholy, and that would put it well within my usual territory. And it’s sort of a counterculture study, focusing on an enclave of homeless people who fervently believe themselves to be richer, happier, and better off all around than the folks with houses and jobs and whatnot, which puts it right down one of my more frequented side alleys. At the same time, though, it’s sort of a bunch of other things that I wouldn’t normally cover at all, like a tearjerker about the plight of people so destitute as to become effectively invisible to society at large, or a current-affairs outrage piece on the Hurricane Katrina debacle. However, one thing Beasts of the Southern Wild absolutely isn’t is the movie portrayed in its advertising campaign, and that’s partly what decided me in favor of writing it up. I can understand why Fox Searchlight would promote Beasts of the Southern Wild as twee Oscar bait, full of Magic Negroes and children wise beyond their years; after all, they know perfectly well who their audience is, whereas figuring out which audience writer/director Benh Zeitlin had in mind for this extremely odd film would take work. Nevertheless, the company’s marketeers are doing both themselves and their product a major disservice, selling the film to a viewership that might not appreciate it once they see what they’re really gotten themselves into, while scaring away others who probably would. Nobody here is teaching anyone to laugh and live and love again, and the central child’s total inability to comprehend the true nature of the events engulfing her is exactly the point.

Somewhere in the farthest southern reaches of the Mississippi Delta, beyond the overworked levees of New Orleans, lies a swampy and low-slung island known to its denizens as the Bathtub. By modern, civilized standards, the Bathtub is completely unfit for human habitation. Too small and too wet for food production at any level above gardening and small-scale animal husbandry, too muddy to support the weight of any building more substantial than a small hut, and too vulnerably situated to be maintained against the meteorological ravages of hurricane season, it’s the kind of place where you wouldn’t expect to find any settlements at all. But those who built the Bathtub’s rather ingenious little shantytown would tell you that it’s modern civilization that isn’t a fit home for human beings. To the Bathtubbers, modernity is a sucker’s game. They look at New Orleans’s pitiless geometry of brick and asphalt, concrete and steel, and cling all the tighter to the verdant, wet softness of the bayou. They consider the city folks’ food, wrapped in plastic and hauled in on trucks from who knows where, for who knows how long, and rejoice in the bounty of crabs, shrimp, and crayfish they pull from the river with their own hands. They think of all the hours their civilized neighbors spend laboring to exhaustion for somebody else— and of how little those hours generally buy of the things civilization values— and immediately drop what they were doing to throw an impromptu party in celebration of their freedom to match their schedules to their needs.

Now maybe not everyone in the Bathtub sees things exactly that way, but a 40-ish man by the name of Wink (Dwight Henry) most assuredly does, and he has worked hard to inculcate his six-year-old daughter, Hush Puppy (an extraordinarily capable kid by the equally extraordinary name of Quvenzhané Wallis) with the same anarcho-primitivist worldview. We might surmise that Wink came by his eccentric perspective as the result of much painful experience trying and failing to make a living in “the Dry World;” certainly he speaks with the voice of one who has discovered a great secret, at great cost to himself. Hush Puppy, however, has never known anything but Bathtub life, and if her daddy says that’s the best kind of life there is, then obviously it must be true. The same applies to the lessons, if you can call them that, of Little Jo (Pamela Harper), the woman who serves as doctor, teacher, and shopkeeper to the Bathtub. Surprisingly young for her role as the village wise woman, Little Jo almost certainly had a fair amount of formal schooling before she dropped out of society and moved out past the levees. Many things can be passed down via oral tradition, but it hardly seems likely that Little Jo learned about the Lascaux cave paintings (one of which adorns her right thigh in tattoo form) sitting on her grandmother’s knee. The Bathtub children, however, will learn of such things, because Little Jo makes it her business to teach them. Her tattoo is a visual aid for lectures about ecology, about humanity’s place in the natural order, about the devastation modern civilization is wreaking on that order. Hush Puppy listens intently to those lectures, and although she’s too young yet to make much coherent sense of them, they do enter into the personal mythology through which she interprets her life. She comes away understanding that the cave men fought with monsters called aurochs when the world was covered with ice, that the last remaining bits of that ancient ice are melting due to the actions of the city people, and that one day the sea will rise up to swallow the Bathtub forever. Little Jo’s talks are Hush Puppy’s Völuspá— creation and eschatology in one— just as Wink’s tall tales of life with Hush Puppy’s mother before she abandoned the family (supposedly by just swimming off toward the horizon one day) are her Eden story.

That eschatology of aurochs and cave men, melting ice and rising seas inevitably colors Hush Puppy’s perception when a storm of unprecedented ferocity blows in from the Gulf of Mexico. Many if not most of the Bathtub’s residents flee to the Dry World, but not Wink. He carries Hush Puppy up to the highest part of his shack, and when that isn’t enough to allay her fears, he plays the part of the hero for her, charging out into the wind and rain with his shotgun to defy the hurricane’s fury until she falls asleep. The storm spends itself before dawn, but the new day breaks on a land transformed. Virtually the whole of the Bathtub is submerged, with only the trees, the tallest of the shacks, and a few bits of formerly high ground protruding above the water. There’s no sign at first of anyone alive save Hush Puppy and Wink, either, although a diligent search turns up Little Jo, four more adults, and a handful of children a bit older than Hush Puppy. It is indeed the end of the world, so far as the little girl can see, and any day now, she expects aurochs freed from melted polar glaciers to overrun the Earth and reclaim it from humanity.

Hush Puppy’s aurochs herd is where the “magic” part of magic realism comes in, and the fact that the monsters exist, on close examination, only in a child’s imagination is the reason why I characterize Beasts of the Southern Wild as merely sort of a magic realism film. A lot of people seem to be missing that point, though, so let’s take a moment now to give it the appropriate close scrutiny. To begin with, these “aurochs” aren’t actually aurochs. The aurochs (they’re extinct now, but small populations survived until the 17th century in parts of eastern Europe) was the species of wild ox from which today’s domestic cattle are descended. Leaner, sleeker, longer-horned, longer-legged, and less sexually dimorphic than most of its human-bred descendants, the aurochs was most similar in size and overall appearance to very old Iberian cattle breeds like the Tudanca or the Spanish fighting bull. The creatures in Beasts of the Southern Wild are something else altogether— gigantic, horned, carnivorous pigs. But while they don’t look anything like a real aurochs, they do look exactly like the pig Wink keeps in the yard behind his shack, only about fifteen times as big and equipped with fanciful natural weaponry. Furthermore, the aurochs are shown throughout the second act only in a fantastic nightmare landscape, totally unlike the naturalistic settings of the film’s main action, and their proximity to the Bathtub tracks with the urgency of several more prosaic threats to Hush Puppy’s safety as she understands it. In other words, they act as a subconscious, symbolic personification (porcinification?) of the terrifying things that Hush Puppy knows are bearing down on her, but can’t fully wrap her six-year-old mind around— and she envisions them as monstrous versions of the biggest animal she has ever personally seen. As for what, specifically, they signify, that would be things like Wink’s heart condition, which will surely kill him one of these days without treatment more efficacious than Little Jo’s herbal potions. Things like the poisoning of the Bathtub ecosystem by the dissolved salts in the seawater inundating it, which triggers a die-off among the birds and beasts of the bayou so conspicuous that even a child can’t fail to notice it. Things like the squads of FEMA agents searching the swamp for survivors, and sending all they find to a network of emergency shelters in the city.

The treatment of the rescue effort is probably my favorite thing about Beasts of the Southern Wild. The sequence in which FEMA rounds up the Bathtub survivors is a brilliant piece of polyphony that ought to (but probably won’t) immunize the movie against the various -ism accusations that inevitably arise whenever white people with money attempt to create art about nonwhite people without any. At issue here is that Wink, Little Jo, and the others don’t want to be rescued. The Bathtub is their home, and they have no intention of leaving it. They bristle at the notion of being confined to a homeless shelter, and being forced to arrange their lives to suit the preferences of people who’ll see them purely as victims and bums. The FEMA agents thus have a fight on their hands bringing the Bathtubbers in, and their “rescue” is effected in the end only by overwhelming them with violence. The shelter is a purgatory of wounded bodies and broken spirits, somehow antiseptic and squalid at the same time, and the rescue workers there treat the inmates with the insufferable well-intentioned paternalism of orderlies in the Alzheimer’s wing of a nursing home. It’s no wonder Hush Puppy and her elders think of nothing but escape from the moment they arrive. Here’s the thing, though— the Bathtub is doomed, and all the pluck and perseverance in the world won’t do shit to change that. Wink is critically ill, and the best mushroom, moss, and tree-bark extracts in Little Jo’s pharmacopeia won’t keep him alive two more weeks with the strain that fighting for survival in a drowned and poisoned wilderness is putting on his defective heart. And although the Bathtubbers plainly see themselves as noble savages (they, and not the imaginary aurochs, are the “beasts” of the title), much of their lifestyle is distinctly ignoble. Wink, for instance, unconcernedly leaves Hush Puppy to live unsupervised in what used to be her mother’s shack, until one day she burns the place to the ground while cooking a pot of cat food stew! The intervention Wink and his companions so forcefully resist is one that they absolutely need, and it isn’t just their own lives at stake. What happens to Hush Puppy when Wink’s ticker gives out on him? What happens to the other little girls whose mothers and fathers apparently drowned in the flood, whom the remaining adults have been caring for in a somewhat haphazard way? The Bathtubbers are people who have nothing in life but their right to self-determination— the political, economic, social, and cultural power structures of modern America already robbed them of everything else. And having been thus robbed, they have persuaded themselves, rightly or wrongly, that they don’t want any of the things they’ve been denied. Nevertheless, in this particular situation, leaving the Bathtubbers alone to live as they wish would mean leaving them all to die, stupidly and unnecessarily. So who gets to make that call? At what point, and to what extent, does a society get to tell its dissenters what they are permitted to value— especially when the society in question has already refused to grant those dissenters what it wants them to value? There’s no obviously right answer in circumstances as extreme as those presented in Beasts of the Southern Wild, and Zeitlin and his collaborators commendably refrain from trying to offer one.

It was an ingenious conceit to treat Hurricane Katrina as a highly localized apocalypse. This is one case where having loutish taste in cinema comes in handy further up-market, because Zeitlin seems to be using a very specific set of visual and thematic cues here. Beasts of the Southern Wild relies very heavily on the vocabulary of schlockier end-of-the-world movies, and conversance with the likes of DEFCON-4 and 2020 Texas Gladiators is likely to grant an appreciation for this film on levels not readily available to the audience toward which Fox Searchlight has been pitching it. The slow death of the environment, the detritus of civilization repurposed for the needs of the New Barbarians (check out Wink’s homemade pontoon boat!), the marauding bands of sinister outsiders seeking to capture the protagonists and force them into what the latter consider an inimical lifestyle— all are commonplaces of trashy sci-fi movies set in the aftermath of nuclear war, pandemic plague, or ecological collapse, so when somebody who knows those movies sees the same stuff here, they immediately go, “Oh! Of course…” And when you put it like that, it’s hard to believe this sort of thing hasn’t been done a hundred times before, since the homeless (those outside a major city especially) already have to live essentially like characters in an Italian Road Warrior knockoff. It hasn’t, though, so Zeitlin and co-writer Lucy Alibar (who also wrote the play from which Beasts of the Southern Wild derives) get my congratulations for dreaming up something that I didn’t know was obvious until after I saw it. And what’s more, they get my congratulations for handling this material in ways neither maudlin nor appalling. I know it seems strange to praise a filmmaker simply for not fucking up egregiously, but you have to keep in mind what a dire disgrace this movie could have turned out to be. Seriously, imagine Robin Williams as a FEMA doctor who learns from Hush Puppy an important lesson about the human spirit, and shudder at the possibilities! When somebody tap-dances through a minefield, their ability to avoid blowing themselves up is always going to look more impressive than any of their specific moves along the way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact