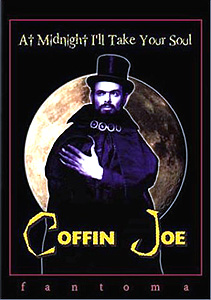

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul/A Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (1964) ***

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul/A Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma (1964) ***

Brazil is not a place most people think of immediately as a country of origin for horror movies, and the reasons why are entirely understandable— there really haven’t been many Brazilian horror flicks in the grand scheme of things. In fact, until 1964, there wasn’t even a single one. But that year, a young director named José Mojica Marins had a vivid nightmare in which a clawed and bearded man in a black cape appeared to him, and took him to see his own grave. After he awoke (and once he had stopped screaming), Marins was struck by the inspiration to shoot a movie that would make audiences feel the same sort of terror that his dream had caused him. At the time, Marins was already scheduled to start work on some cheesy little juvenile delinquent movie for some cheesy little studio in São Paolo, but somehow he convinced his bosses at the production company to take him off that project, and let him make his horror film instead. The resulting movie, At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul/A Meia-Noite Levarei Sua Alma, stunned virtually everybody involved in its creation by becoming a gigantic hit, and Marins would continue cranking out sequels even into the 1980’s. Apparently there was even a “Night Gallery”-like series built around this movie’s central character, which aired on Brazilian TV in 1968!

That main character, Zé do Caixão (his English-language nickname, Coffin Joe, is a more or less direct translation— Zé is short for José, while caixão means “coffin” in Portuguese), is much of what makes At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul so compelling in spite of its often awkward amateurishness, as well as the factor that makes it most difficult for a non-Brazilian audience to appreciate the film. Simply put, though Caixão (played by Marins himself) is a fascinating and memorable character, it takes a bit of mental effort for non-Brazilians to understand why audiences in his native land found him so shocking and horrifying. The first half of At Midnight I’II Take Your Soul is devoted almost exclusively to introducing Caixão and examining what makes him tick. He works as an undertaker in the small, rural village where he lives with his wife, Lenita (Valeria Vasquez). Lenita is quite devoted to her husband, which is a bit surprising given how most of the other townspeople regard him. The uneducated, superstitious, and staunchly Catholic villagers consider the nihilistic, atheistic, and outspokenly iconoclastic Caixão to be virtually equivalent to the Devil himself. Zé, for his part, absolutely relishes his neighbors’ fear and hatred of him, going out of his way to offend their sensibilities and belittle their beliefs. Not even Antonio de Andrade (Nivaldo Lima, who later turned up in this movie’s sequels, This Night I Will Possess Your Corpse and The Strange World of Coffin Joe), the only man in town who considers Zé his friend, is safe from the undertaker’s barbed tongue, although their friendship is enough (at first, anyway) to spare Antonio from Caixão’s most aggressively antisocial antics. Antonio may get lectures about the falsity of religion and the stupidity of rustic folkways, but Caixão never forces his friend to join him in eating meat on Good Friday, horsewhips him when he tries to come between Zé and a pretty barmaid, or cuts off his fingers with a broken bottle when he tries to weasel out of a gambling debt. (All of those fates and more befall the men who cross Coffin Joe at one point or another.) Truth be told, Zé has it pretty good. His livelihood is pretty much recession-proof, making him one of the wealthiest men in the village, he has a loving wife and all the friends he really needs, and the townies he so despises are all so terrified of him that he can basically do entirely as he pleases without having to fear consequences of any kind.

There is one thing Caixão wants that he can’t have, however, and without that thing, he will never be content. Believing as he does in nothing at all of religion or morals beyond Nietzsche’s Will to Power, Caixão considers that his life will have no meaning unless and until he can immortalize it in the only way that his radically materialist philosophy will countenance— by fathering and raising a son. Lenita is barren, however, so as long as he remains bound to her, Zé can never know spiritual peace. It is for this reason more than any other that Zé’s eye wanders the way it does, especially in the direction of Antonio’s fiancee, Terezinha de Oliveira (Magda Mei, who also contributed to this movie’s screenplay). Eventually Caixão reaches the obvious conclusion, and in accordance with Nietzsche’s postulate that “thy will is thy law,” he sets about acting on that conclusion.

Step one is to get rid of Lenita. Caixão chloroforms her and then lets loose a deadly tarantula to bite and poison her. When Dr. Rodolfo (Ildio Martins) examines her body, he finds nothing wrong with her but the spider bite, and rules the death an accident. Step two is the elimination of Antonio, who makes the mistake of inviting Zé over for a drink one night soon thereafter. Caixao brains his old friend with a fireplace poker, and then drowns him in the bathtub, rubbing the dead man’s bloody scalp on the edge so as to make it look like Antonio slipped and knocked himself out while drawing a bath. Terezinha has known for some time that her boyfriend’s avowedly amoral buddy has been eyeing her, however, and she puts the pieces together almost immediately. Before she gets a chance to do anything with those assembled pieces, though, Caixão comes by her place on the pretext of offering her a gift of condolence. Once inside the house, the undertaker rapes Terezinha, ensuring (or so he thinks) that his bloodline will continue after all. Terezinha has other ideas. While Caixão is on his way out the door, she swears that she will kill herself rather than bear his child. And having done so, she continues, she will return from beyond the grave to wreak her revenge: “At midnight Antonio was buried, and at midnight, I’ll take your soul!” Zé do Caixão can scoff all he wants, but when the Day of the Dead rolls around in a couple of weeks, he’s going to find out just how real the spirit world is.

So just what was it about this curiously philosophical little fright film that made it go through the roof in its motherland, even as it was ignored completely by the rest of the world for some 30 years? It helps to know a little bit about what life in Brazil was like in the mid-1960’s. Brazil has always been one of the more developed Latin American nations, but in 1964, that wasn’t saying a whole lot. Most of the country’s population lived in insular little villages just like the one depicted in At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, and even in the big cities, many people could trace their origins to such places. In addition, Roman Catholicism enjoyed an almost totally unquestioned hegemony over the country’s intellectual life, with the result that the average Brazilian saw the world in much the same way as the villagers Coffin Joe spends most of this movie abusing. In a context where most people fully believe in the literal reality of Hell, and uncritically accept the necessity of an organization like the Catholic church to guide them safely through the thickets of heresy to the One True Doctrine that will keep them from spending eternity there, such images as Caixão gleefully devouring a leg of lamb in full view of a religious procession on Good Friday night would be profoundly disturbing. The same goes for his habit of getting drunk and loudly taunting God, the angels, and the spirits of the venerated dead. What makes Zé do Caixão unique to the best of my knowledge is that he is a horror movie villain who is meant to be frightening not so much because of what he does, but rather because of what he believes. The almost medieval mindset that is necessary for such a figure to take root in the popular imagination is something that most people in the US can probably scarcely imagine. Thus the alien assumptions from which At Midnight I’II Take Your Soul proceeds can easily serve as an impediment to the uninitiated, but for those who are specifically looking for something different, the movie becomes attractive for precisely the same reason.

At the same time, At Midnight I’II Take Your Soul is also probably the best place to start delving into what the title of one sequel would later call the strange world of Coffin Joe. Not only is it the beginning of the story, it is also among the most conventionally constructed, and thus most accessible, entries in the series. Visually, At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul bears a close resemblance to Hollywood horror films of the early 30’s, the Universal gothics especially. (What’s below that surface, however, is something else altogether.) To some extent this was probably deliberate, but given that filmmaking technology in Latin America was in many respects about 30 years behind that of the United States at the time, a certain similarity to the likes of Dracula and Frankenstein was most likely inevitable for purely technical reasons. In any event, Marins would move beyond the Universal look very quickly; the first sequel, This Night I Will Possess Your Corpse, already displays a drastically different and altogether more personal visual sensibility, along with a much more daring approach to things like editing and production design, most likely made possible by the significantly increased budget Marins enjoyed the second time around. The speed with which Marins progressed into unexplored stylistic territory isn’t too surprising, though, because what stands out most about At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul is how little the movie owes to anything else that came before it— probably because, in Brazil at least, nothing came before it. What we see here is very nearly a reinvention of the horror film, almost totally independent of what had gone on elsewhere in the world during the preceding 60 years. And though some of the more extravagant claims for Marins’s talent and ability that have been made in cult-film circles of late overstate the case, he unquestionably deserves a tremendous amount of credit for pulling that trick off as well as he does here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact