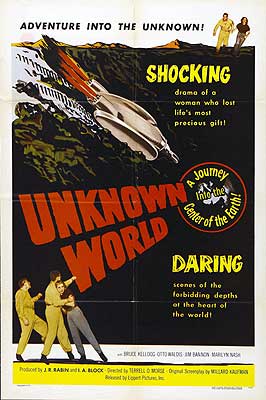

Unknown World/To the Center of the Earth (1951) *½

Unknown World/To the Center of the Earth (1951) *½

I know I’ve touched on it here and there, but I don’t think I’ve ever given the subject of hardness in science fiction its proper due. In theory, sci-fi differs from other genres of the fantastic in that its departures from present-day reality are governed and constrained to some extent by the potential of future reality. While fantasists of other stripes are permitted to make things up willy-nilly, sci-fi writers are supposed to extrapolate. They’re supposed to take their cues from technological, sociological, or political trends, to populate their imaginary environments within plausible biological and ecological bounds, and in general to supply reasons that will stand up to scrutiny for why things are the way they are in the worlds that they create. In practice, however, authors working within the genre have always felt free to decide arbitrarily how broadly and rigidly to apply those principles, depending on the kinds of stories they sought to tell. Among other breeds, there are Greg Bear types who try to make everything fit together like a precisely engineered machine; H. G. Wells types who don’t give a shit how the gadgets work, but are rigorous indeed about their social and moral implications; Robert Heinlein types who mainly want to test-drive their theories about the Way Things Ought to Be; and Edgar Rice Burroughs types, who make a ritual genuflection or two in the direction of the facts (Mars is cold, dry, little, and geologically inert, so Barsoom is all those things too) before letting their imaginations run riot. They’re all perfectly valid approaches, but they cater to different tastes and mindsets, so there’s a practical need for terminology to distinguish among them. Thus “hardness,” which refers to how much control the “fiction” side of the hyphen yields to the “science” side. Bear is a hard sci-fi writer, while Burroughs is as soft as they come. Wells and Heinlein are somewhere in between.

Implicitly, though, there’s more to it than that. Any given level of hardness carries with it expectations about style or mood, with the hard end of the spectrum leaning toward sobriety, reserve, and an emphasis on the cerebral. It doesn’t need to be that way, of course, and exceptions surely exist. But when I pick up a book or a movie presented as hard sci-fi, I don’t anticipate much humor, violence, or eroticism, for example. That’s because writers who strongly value such things tend to value them more than airtight scientific credibility, and thus tend not to write stories that can plausibly be sold under the banner of hard science fiction.

The latter point is what makes Unknown World so curious. With its leaden pace, grim subject matter, dour characters, and complete lack of whizbang, Unknown World has all the stylistic hallmarks of a hard sci-fi film. Its central technological marvel, a huge tunneling machine called a Cyclotram, is thoroughly functional in appearance, and might even have been within the capabilities of early-50’s heavy industry, had there been any compelling reason to build such a thing. While other movies about exploring the Earth’s interior fill the fathomless depths with prehistoric monsters and lost civilizations, Unknown World envisions nothing more exotic down there than a species of luminescent algae bright enough to sustain photosynthesis in other plants. The film is every inch as starchy, preachy, sullen, and self-serious as any nightmare vision of hard science fiction ever strawmanned up by fans of the softer stuff, too. Yet Unknown World disqualifies itself as hard sci-fi as soon as it gets the chance, dismissing everything that was known or suspected about conditions within our planet in favor of a bunch of made-up crap that better suited the story the filmmakers wanted to tell. What we have here, then, is a movie with all the vices of hard science fiction, but none of the virtues.

I do rather like the gimmick of beginning with a fake newsreel, though. It justifies the voiceover narration that far too many of the era’s later sci-fi cheapies would rely on, and creates a sturdy framework for an incredibly dense exposition dump. Dr. Jeremiah Morley (Victor Kilian, of Dr. Cyclops, who goes uncredited despite his leading role because he was blacklisted by the time Unknown World was ready for release) believes that nuclear war is inevitable, and that such a war will leave no part of the Earth’s surface fit for human habitation. (An impressively prescient vision in 1951, requiring a sense for how several as-yet-immature technologies might come together once all the bugs were sorted out.) Nevertheless, Morley is not prepared to concede that the human race is doomed. Rather, he takes the ticking nuclear clock as his goad to seek out a human-hospitable environment inside the Earth— the ultimate bomb shelter, deep enough underground to be unaffected by even the maximum possible nuclear exchange and beyond the reach of the severest radioactive fallout, where the survivors may live not just for a few weeks or months, but long enough to recreate a sustainable society no matter how bad things are upstairs. It’s a wild vision, but one that speaks to many in the scientific community. Soon, Morley begins attracting followers: geophysicist Max Bauer (Otto Waldis, from Attack of the 50-Foot Woman and The Black Castle); physician, biochemist, and “ardent feminist” Joan Lindsey (Marilyn Nash); metallurgical engineer James Paxton (Tom Handley); soil conservationist George Coleman (Dick Cogan, of Riders to the Stars); and even a non-scientist, the decorated ex-military demolitionist and explosives expert Andy Ostergaard (Jim Bannon, from Soul of a Monster and Phantom from Space). Morley and his team style themselves the Foundation to Save Civilization, and get to work developing the equipment they’ll need to find humanity a new home a thousand miles below the planet’s surface.

Wait— a thousand miles?! Shouldn’t there be nothing but a churning, uninterrupted mass of molten rock that far down? Why no, assures Dr. Bauer. Contrary to everything you’ve ever heard about geology, the Earth, like all spheres, is coolest at the center. Furthermore, far from being uninterrupted rock in any physical state, the planet is riddled inside with fissures and void spaces all the way down to the core, many of them scores or even hundreds of cubic miles in extent. Okay then. But as it happens, the feasibility of Morley’s project is less of a sticking point than its cost. The scientists have been counting on a grant from the Carlisle Foundation to pay for the actual expedition (their own resources being adequate only to cover research and development), but the president of that outfit (George Baxter, from She Devil and The Flying Saucer) balks when he sees all the zeroes in the price Morley quotes him. Thus ends the newsreel, with the apparent stillbirth of the project and the shuttering of the Foundation to Save Civilization.

We now learn that everything we just saw had an in-movie audience as well, composed of all six members of the defunct society of scientists. They’re not happy at all with the tone of the newsreel, grumbling that it paints them as a pack of millenarian loonies unmoored from the practicalities of everyday life, and whipping up scare stories to put themselves in the spotlight. Nor are they a bit surprised by that, because the studio that produced the film is owned by Wright Thompson, whose journalistic empire has cast scorn and aspersion on their work at every step. Morley and Lindsey, the hotheads of the group, believe that Wright Thompson Jr. (Bruce Kellogg) arranged for them to preview his father’s latest salvo as an excuse to gloat, but they’re entirely mistaken. The younger Thompson doesn’t give a rat’s ass for shaping public opinion, and like many scions of wealth, he tends to figure there’s no disaster too dire for him to buy his way onto the lifeboat when the time comes. However, Wright Jr. also has the scion of wealth’s pathological intolerance for boredom, and digging a hole to the center of the Earth in search of an emergency habitat for humanity is just about the most exciting idea he’s ever heard. He has his own money, too— so much that he could never make a dent in it through conventional thrill-seeking— and he offers Morley and the others a deal. Thompson will pay for the whole expedition out of his own pocket, but only if he gets to come along. The scientists are hesitant (Lindsey in particular hates the idea), but eventually they decide that the fate of humanity is too important to be risked over their distaste for hitchhikers.

I hope you really like Carlsbad Caverns, because that’s just about all you’re going to see from here to the closing credits. No iguanas tricked out with Dimetrodon sails; no forgotten offshoots of Sumerian civilization farming mushrooms with enslaved mole-men; no telepathic, anthropophagous pterodactyl people; and certainly no half-naked cave girls. In fact, circumstances down in the mantle are so determinedly ho-hum that writer Millard Kaufman must resort to the most absurd contrivances to put the explorers in any real danger. For example, while boredom and persistent failure sap his colleagues’ will to continue, Paxton succumbs instead to cabin fever, and becomes convinced that he’s John Galt. He storms out of the Cyclotram on his own, ranting all the while that people— present company most definitely included— are sheep who need to be led by the great and the bold. Unfortunately for him, even the überest of Übermenschen need gas masks to breathe in a methane pocket, so Paxton’s foolhardy foray gets not only himself killed, but also Dr. Coleman, who followed him out to make sure he didn’t do anything catastrophically stupid, but didn’t bring his gas mask along, either. More ersatz drama is trumped up via an implausible will-they-or-won’t-they romance between Lindsey and Thompson. (“Ardent feminist” my ass— although she does at least refrain from ever serving anyone coffee.) Unknown World’s closest approximation of real drama comes when neither of the two potential underground safe havens pan out— the first because it’s a lightless pit of misery with more petroleum than potable water, and the other because there’s something in the air down there that renders Lindsey’s experimental rodents incapable of bringing a pregnancy to term successfully. Morley kills himself in despair, and the others are forced to admit that there’s nothing else for it but to go home and devote their energies to making sure we don’t ruin the only home we’ve got.

I don’t think that ending was supposed to come across as downbeat as it does. But after 70-odd minutes of unalloyed gloom and futility, it really does feel less like “Alright, gang— let’s go back up and get it right this time!” than “Oh well… If we’re all going to die in atomic fire anyway, we might as well do it in the sunshine.” Honestly, that glum fatalism, so different from the can-do attitude of most 50’s sci-fi, is one of the few really interesting things about Unknown World. Also preventing it from being totally without merit is the treatment of Dr. Lindsey, at least until she starts mooning over Wright Thompson Jr. for no discernible reason. During the first half of the film, she’s much pricklier than movies of this vintage generally allowed their heroines to be without pushing them overboard into irrational, unpleasable bitchiness. When Lindsey gets her hackles up, there’s usually a very good reason. I also like that her diary is one of the devices Unknown World uses to keep us apprised of how the mission is going. It makes her a real viewpoint character, which is a rarity in this presumptively male-oriented genre. Otherwise, Unknown World offers very little to like at all.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact