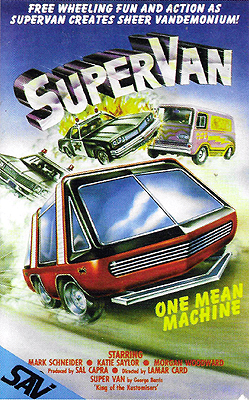

Supervan (1977) -**½

Supervan (1977) -**½

I was a little, little kid at the time, but I actually remember the whole van thing. In fact, it’s one of the very few pop-culture phenomena from my earliest childhood that I do vividly recall. There were several customized vans in the Hyattsville neighborhood where I spent my first three years, but the one that impressed me most was this big black bastard— the kind with no windows aft of the front doors except for a couple of convex deadlights in the upper rear corners of the sidewalls— covered all over with red and yellow airbrushed flames. This was no ordinary hot-rodder flamejob we’re talking about. Whoever painted it had close to 90 square feet to work with on each side of the van, and he’d used damn near every one of them. The aforementioned rear-corner deadlights, meanwhile, were tinted purple and vacuum-formed in the shape of mushrooms, which might be taken in retrospect to imply a few things about the vehicle owner’s tastes in recreational pharmacology. (Incidentally, I’ve got a little “kids are weird” anecdote hinging on those purple plexiglass mushrooms. With the sideways linguistic logic characteristic of preschoolers, I spent years baffling my elders by referring to any similarly positioned automotive deadlights as “mushroom windows,” regardless of their actual shape.) There was even a prominent antenna for one of the citizen’s band radios that the public had gone gaga for as part of the concurrent fad for idolizing long-haul truckers, and although I never got a look inside to confirm that the interior was completely covered in brown shag carpeting, I’m sure it must have been. Anything less would have been an intolerable oversight.

This van and the two or three others more or less like it were invariably the cleanest, shiniest, best-maintained vehicles in the whole neighborhood, for a custom van in the 70’s was no mere mode of transportation. Rather, it was a personal statement, a mobile party pad, and a masculine courtship display, all at the same time, and no amount of time or money was too great to invest in its creation and upkeep. Indeed, the weirdest mutation of the custom van phenomenon that I ever saw was obviously the work of someone eager to take part in the craze during its waning days, but unblessed with the resources necessary to do it up right. One weekend afternoon, in the parking lot of the Annapolis Mall, I encountered a 1980 Chevette whose owner had dubbed it the “Blue Demon,” and subjected it to the full treatment: CB radio, tinted windows and headlight lenses, aftermarket chrome trim, flamejob on the fenders and Luis Royo-style fantasy art airbrushed across every body panel spacious enough to accommodate such embroidery. Obviously this was not a hobby that most people could pick up using just their own preexisting skills and talents, so it was only to be expected that a complete subcultural infrastructure quickly arose to support the needs of van customizers. Parts suppliers were only the beginning; there were also how-to books, magazines, a sort of national convention circuit in the form of informal auto shows organized in many cases by the vanners themselves, and even the odd bit of tie-in entertainment media. The latter is what we’re really here to talk about, for bizarre as it sounds, there were indeed a handful of vansploitation movies produced during the late 1970’s. And while most of them seem to have been essentially ordinary youth-oriented T&A comedies, Supervan is something altogether stranger. Calling it a youth-oriented T&A comedy wouldn’t be too far off the mark, but there’s nothing ordinary about Supervan.

Clint Morgan (Mark Schneider, from The Premonition and The Supernaturals)— known to his friends as “Morgan the Pirate”— is an eighteen-ish lad from someplace in the eastern sector of the Midwest. Much to the consternation of his father (Ralph Seeley), Clint sinks practically every penny he makes into spiffying up the crapwagon mid-60’s Ford Econoline that he affectionately calls the Sea Witch. When we meet Clint, he is about to embark (also much to his father’s consternation) on a journey to the Kansas half of Kansas City for Freakout ‘76, the second in a series of annual van-customizing competitions sponsored by Trenton Oil, Mid-American Motors, and the Kansas City-based radio station KVAN. A $5000 prize will be awarded to the van that wins three out of the five major events, and Clint is sure that with a bit of last-minute tweaking by his engineer buddy, Bosley Birdwell (Tom Kindle)— who, it just so happens, works as a van designer for the aforementioned Mid-American Motors— the Sea Witch will have a credible shot at the five grand.

Maybe it would have, too, but we’re never going to know for sure. Clint habitually keeps the Sea Witch’s CB scanning the airwaves whenever he’s on the road, and while en route to Bosley’s laboratory, he picks up a biker named Grinder (Richard Sobek) and one of the other guys in his gang as they discuss raping the girl they have cornered in the junkyard where they hang out. Clint knows the junkyard in question, and he gallantly stages what he means as a precision rescue raid— speed in, disrupt the attack, grab the girl, speed out. What really happens, though, is that he manages to get the Sea Witch’s rear end jammed in the mouth of the car crusher while executing a three-point turn during the getaway, and before he knows it, he and Karen Trenton (Katie Saylor, from Invasion of the Bee Girls and The Swinging Barmaids) are dumbfoundedly watching the huge machine smash the Sea Witch into a neat little cube. Luckily, Grinder’s bike meets the same fate immediately thereafter, giving the kids an opening to flee far enough on foot to hitch a ride to actual safety. In fact, their rescuer even gives them a lift to Bosley’s lab.

Now, notice that the name of the girl Clint saved from those bikers is Karen Trenton. That’s Trenton as in Trenton Oil, the sponsor of Freakout ‘76, meaning that Karen’s dad, T.B. Trenton (Morgan Woodward, of Battle Beyond the Stars and The Sword of Ali Baba), is Bosley’s ultimate boss, as Trenton Oil is the parent company of Mid-American Motors. Karen’s keeping her family ties on the downlow for now, however, because it was precisely to escape from her father’s influence that she went out on her present cross-country ramble. Those family ties are going to work greatly to Clint’s advantage later on, but that’s all third-act stuff. For now, the connection between T.B. Trenton’s two companies is a lot more relevant than the one between him and his daughter, for Bosley’s current assignment is to develop the new Trenton Trucker, an enormous, shoddily made, gas-sucking monstrosity of a van aimed directly at hobbyists like Clint, and specially formulated to keep them buying the parent firm’s petroleum products in the maximum possible quantities. Bosley, however, wants nothing to do with any such screw-job. Instead, he’s been secretly devoting his energies to Vandora, a solar-powered, computerized super-van that would revolutionize the market if only Trenton would allow it to be sold in the first place. He won’t, naturally, but Bosley’s contract stipulates that he owns all prototypes from his lab until such time as Trenton deems them ready for production, and the designer has a scheme of his own to outmaneuver the boss. Nevermind the recently deceased Sea Witch, tragic though her fate may have been. Clint is going to take Vandora to Freakout ‘76, where Bosley has no doubt that it will take all five events in a walk. Trenton will then have only two choices: scrap the Trucker and put Vandora into production instead, or watch Mid-American Motors lose the lucrative van market to whichever competitor buys the supervan design from Birdwell. Meanwhile, to circumvent the rule against Trenton employees entering the contests at Freakout ‘76, Bosley signs over ownership of Vandora to Clint, who will keep the $5000 that he’s now certain to win.

The one snag in this plan is that Birdwell doesn’t work completely alone at his lab. The one other staffer we ever see rats him out to Trenton immediately after Clint’s departure, and it takes the tycoon very little time to discern how fucked he’ll be if Clint enters Vandora in Freakout. He reports Vandora stolen at once, then dispatches henchmen of his own (the same henchmen who hire his whores, I might add) to keep Clint away from Kansas City should the police fail. Meanwhile, he also recruits a vanner named Vince (Skip Riley)— a possessive ex-boyfriend of Karen’s, interestingly enough— to act as his agent in the competitions themselves, although what exactly he expects to gain from that is difficult to say. The upshot is a succession of cross-country motor vehicle chases that make Supervan as much a Smokey and the Bandit cash-in as a vansploitation movie. It’s Clint’s good fortune that his new girlfriend is the one person on Earth who might be able to charm T.B. Trenton into going easy on him, and that Bosley had the foresight to recognize the appeal of radio jammers and laser cannons as accessories for the vanner who has it all.

Supervan devotes relatively little of its running time to the story I’ve just described. Rather, the plot exists almost solely as an excuse to get us to Freakout ‘76, so that we can divide our ogling attention more or less evenly between scantily clad (and conspicuously braless) girls on the one hand, and totally boss customized vans on the other. The former attraction is best represented by the wet t-shirt contest in which the contenders are hosed down by hard-drinking counterculture icon Charles Bukowski, who remarkably received no screen credit. (I don’t know about you, but I’d have exploited the fuck out of that cameo had I been the producer of Supervan!) The latter attraction reaches its apotheosis with one truly astonishing vehicle that has a spaghetti Western gunfight overseen by a hovering cloud goddess, a man turning into a tiger, and a bunch of stern-looking rednecks painted across one side; an almost indescribably busy Escheresque street scene (complete with King Kong perched atop the tallest building on the horizon) painted on the other; and a grizzly bear, a nude woman, a weirdly muscular Mickey Mouse, and a huge disembodied hand giving the victory sign painted on the tail. Frankly, the cheaply rigged and generically futuristic Vandora is nowhere near as impressive as this ridiculous machine. Freakout is also the occasion for loads and loads goofball hippy honky-tonk on the soundtrack, along with some notionally comic subplots involving Martin “the eVANgelist” Dimsdale (John Chambers, of 69 Minutes) trying to prevent his young and pretty wife (Cheryl Hepler) from screwing every male at the convention, and a pair of hitchhiking girls (Cindy Allison and Jackie Riggs) who have the lousy luck to get picked up by a vanload of hunky guys who turn out to be all homosexuals. Director Lamar Card has very little else on his resumé in that capacity (although he did a fair amount of second-unit work as well), but if Supervan is indicative of the sensibility he brought to cashing in on ephemeral pop-culture manias, then I may need to give his slightly later Disco Fever a try, too, one of these days.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact