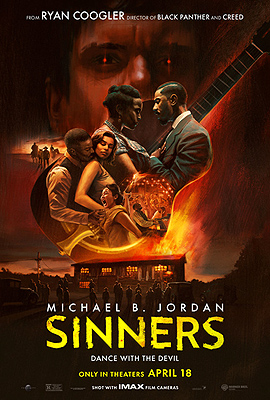

Sinners (2025) ***½

Sinners (2025) ***½

Music is magic. Not everyone who plays has that kind of power (I don’t think I ever did), and not everyone who has it can wield it consistently, but there’s no mistaking when you’re in its presence. When the Cro-Mags played the old 9:30 Club in the summer of 1990, the opening bars of “We Gotta Know” cast a spell on that room. They called the lightning from the atmosphere and the fire from the guts of the Earth, and channeled them straight up all our spines to awaken parts of our brains so ancient and savage that even apedom represented a taming advance over them. Other sorcerers of song conjure more subtly, but with no less force: they make Joy a tangible, live thing that leaps from heart to heart through the crowd; they invite the indwelling of the Eternal Trickster; they make strangers feel like they’ve known each other for fifteen years. And whatever the main effect of the casting, for as long as it remains in operation, time hangs suspended and irrelevant, as if there’s never been another moment but this one right now, nor ever will be again. So insistently, undeniably numinous is music that not even the most dour and joyless of religions can afford to put it aside. Jehovah’s Witnesses, who reject the entire concept of holidays, nevertheless sing in their Kingdom Halls, and Iran’s ayatollahs expressly exempted sacred music from what was otherwise a blanket ban during the first and most severe decade of the Islamic Revolution. Ryan Coogler’s Sinners is about a great many things (indeed, it could maybe have stood to be about one or two fewer), but at its innermost core, it’s about the mystic, uncanny, and ultimately uncontrollable power of music.

In the depths of the Great Depression, Clarksdale, Mississippi, is one of the poorest municipalities in the poorest state in the Union. The town’s permanent underclass consists mainly of three demographic elements, all of which share in various ways the experiences of displacement, exploitation, and alienation from a homeland and way of life nearly forgotten. There are the remnants of the Choctaw nation, for starters, still clinging to dwindling fragments of their ancestral territory 100 years after the Indian Removal Act. Then there are the Irish and Scots-Irish, whose forebears were driven from the Old Country first by the enclosure of the commons, then again by the famines that resulted during the 19th century. And most of all, there are the blacks, descendants of slaves whose erstwhile owners and overseers have demonstrated limitless ingenuity at preventing freedom from ever becoming all that it was cracked up to be. All three subcultures, as it happens, have ancient traditions indeed regarding the spiritual power of music, antedating by eons their calamitous three-way collision 300 years earlier. And although they all have their own unique names for and understandings of such abilities, neither Choctaw nor Irish nor black would need any prompting to recognize that it isn’t just mortals who prick up their ears when teenaged Sammie Moore (Miles Caton) straps on his guitar to play the blues. Indeed, Sammie’s father, Jedidiah (Saul Williams), who preaches at one of Clarksdale’s shabbier black churches, wishes the boy were more careful with his gifts, since the Devil loves music as much as any un-fallen angel.

As a practical matter, though, the devils that Jedidiah fears most on his son’s behalf are his twin cousins, Elijah and Elias— better known as Smoke and Stack (and both played by Michael B. Jordan, of Fahrenheit 451). The Smokestack Twins left Clarksdale more than a decade ago to make something of themselves by any means available, and not one of the professions they’ve tried would meet with a preacher’s approval. The brothers fought with the American Expeditionary Force in the Great War, then settled in Chicago to serve as go-betweens for both Irish and Italian mobs looking to do illegal business with the city’s black community. Legend has it they killed their own father, too, before setting out— although anybody who actually knew the man would call that the closest thing to a good deed the twins ever committed.

Anyway, Smoke and Stack are back in town now with a satchel full of cash and a truckload of bootleg beer and wine stolen from their former big-city business partners. They plan to use the money to acquire a venue for selling the booze, buying a long-disused textile mill from a shady good ol’ boy by the apt name of Hogwood (David Maldonado, from Domain of the Damned and The Tomorrow War). Then over the ensuing days, the brothers lay all the groundwork necessary to transform that mill into Club Juke, the first authentic Chicago speakeasy in northern Mississippi. They arrange to buy fully 100 catfish from Bo Chow the grocer (the enigmatically mononymous Yao), and a pair of painted signs from his wife, Grace (Li Jun Li), who runs the better-equipped store on the white side of Main Street opposite Bo’s. To get all those fish fried, Smoke patches things up with his estranged wife, Annie (Citadel’s Wunmi Mosaku)— whose talents as a hoodoo conjure-woman will come in even handier than her cooking skills before opening night at Club Juke is at an end, although neither she nor Elijah has any reason to suspect that yet. They get a brawny sharecropper called Cornbread (Omar Benson Miller, of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice) to work security and take admission. And most importantly, the twins hire the most talented musicians they know to headline the evening’s entertainment. At one extreme of age and experience, that means luring hard-drinking old blues polymath Delta Slim (Delroy Lindo, from Malicious and The Blood of Heroes) away from his long-established residency at one of Clarksdale’s above-board dancehalls. And at the other, it means giving Sammie Moore his first real chance to shine on a public stage.

Elsewhere in the Clarksdale hinterland, in the twilight accompanying the dusk, a terribly sunburned man (Eden Lake’s Jack O’Connell) arrives on the doorstep of a white dirt-farmer by the name of Bert (Peter Dreimanis). This fellow— Remmick, he’s called— explains that he’s being pursued by Choctaw bandits, and implores Bert and his wife, Joan (Lola Kirke), to hide him. Although the couple exhibit the usual country-folk wariness of strangers, race solidarity wins out on this occasion, and Bert agrees to take Remmick in. His enemies turn out to be close behind him indeed, and Joan quickly finds herself brandishing a shotgun at them from the front porch of the cottage. If you’re asking me, though, the Indians who come inquiring after Remmick don’t look like bandits. They seem too organized, too disciplined— more like bounty hunters, deputies, or even some kind of reservation militiamen. Just the same, the Choctaws all understand that they’re at a disadvantage coming onto the property of even the lowliest whites. Their leader merely admonishes Joan that the man they seek is not what he seems before climbing back into his truck and driving off. But at that very moment, Bert is discovering just how right the Indians are. Despite his unimpressive appearance, Remmick is a vampire so ancient that he personally remembers when Christianity came to Ireland to supplant the ancestral faith of his people. He kills both Bert and Joan, and resurrects them to become the nucleus of a new undead clan.

Obviously Remmick, Bert, and Joan are destined to become a problem for the folks at Club Juke, and if you’ve been paying attention to all my harping on the power of music, then you should have at least an inkling of how. Opening night at the club is a roaring success in terms of both turnout and enthusiasm (although the plantations’ standard practice of paying their black field hands in company scrip means that it’s rather less successful from a strict business point of view). And when Sammie Moore takes the stage, his playing draws in a whole second audience from the spirit world, as ghosts from the past and shadows of the future come to join the party. Unfortunately, the vampires too are drawn to the festivities at Club Juke, with music and magic of their own to contribute. Nor, in the vampires’ understanding, is their interloping simply an act of depredation, for the way they see it, theirs is a transcendent state offering benefits aplenty to mortals. Indeed, they’d tell you that it’s an especially good deal for mortals downtrodden by systems of officially sanctioned bigotry and exploitation, since one of the defining facts of their condition— a kind of shared consciousness somewhere between a telepathic bond and a full-on hive mind— inescapably imparts to them a form of unity and fellow-feeling that no human has ever known.

I wish Sinners were a little tighter, and struck a somewhat different balance among its many, many moving parts. It’s a long movie, and the section devoted to getting Club Juke up and running drags in places, even as some of the most interesting and original ideas in the subsequent vampire-siege phase are left underdeveloped. That said, it’s impossible to fault writer/director Ryan Coogler’s ambition on this project. It’s been a long time since I saw a first-run movie take on so much, textually, subtextually, and technically alike. Fittingly, the best place to see what Coogler was aiming for throughout Sinners is in the sequence that shows Sammie’s performance ensorcelling the club. On the most literal narrative level, we see at last what the movie has teased several times already, as the spirits descend on the dance floor from future decades and past centuries to join in the revelry. 90’s flygirls and 80’s DJs and 70’s space-rockers start filtering through the crowd alongside masked tribal dancers, chanting Maasai warriors, and 17th-century slaves strumming handmade banjos— plus a handful of phantom Chinese opera performers, lest Bo and Grace feel left out of the conjuring! And of course the specific identities of these spectral partygoers emphasize both the cultural continuity of black music, however much the style and technique might change over the ages, and its role in creating havens against a hundred forms of oppression and adversity. As befits the centrality of this sequence to the movie as a whole, Coogler and his collaborators behind the camera pulled out all the stops to create a suitably preternatural visual presentation while taking as little recourse to computerized shortcuts as possible. (I’ve read that the IMAX version of Sammie’s star turn employs some truly breathtaking frame-formatting trickery, too, but I’m a cheapskate who furthermore finds IMAX physically painful to watch, so I’ll have to take that on trust.) Coogler gives a similar treatment as well, during the siege on the club, to Remmick leading his ever-growing clan of vampires in an evil-spirited rendition of “Rocky Road to Dublin,” but it doesn’t have quite the same impact, because the director seems less certain of what he’s trying to accomplish there in plot terms.

Thematically, though, Coogler is crystal-clear about the meaning of the vampires’ jig, which brings me to the element of Sinners that has the greatest resonance for me personally. Alongside the power of music, the film’s most consistently visible through-line is the notion of outsiderdom, and the extremes that outsiders are driven to in order to survive, let alone to thrive. With the sole exception of Hogwood, all of this movie’s characters are outsiders in some way and to some extent— even Bert and Joan, who exist on Clarksdale’s economic margins, despite belonging to the locally favored racial group. And what we consistently see for all of them is that the only way to rise even a little bit above the baseline of poverty and degradation is by doing something disreputable. Sammie and Delta Slim play the blues in dens of vice and iniquity. Annie practices hoodoo. Bo and Grace run businesses serving both sides of the color line. Bert clandestinely belongs to the officially disbanded Ku Klux Klan. The Smokestack Twins have just about done it all. And Remmick, of course, is a vampire. Dig an inch below the surface, and the central conflict of Sinners resolves into a clash between those outsiders whose deprecated coping strategies work by building up their own communities, and those who get ahead by tearing somebody else’s down.

That’s what makes it so fitting that Sammie, despite being the primary viewpoint character, isn’t really the protagonist of Sinners. Instead, this is primarily the Smokestack Twins’ story, as they’re alternately tempted and forced to come down on one side or the other of that divide, which they’ve thus far spent their whole lives straddling. And tellingly, that’s a conflict that Elijah and Elias each face within themselves, rather than forming some good twin/bad twin dichotomy. Smoke may be the practical, level-headed brother who wants to run Club Juke as much like a legitimate business as possible, but that also makes him the ruthless one who wants to refuse the plantation scrip that many of his would-be customers have no choice but to use if they want to buy anything. Stack is the impulsive, hot-headed one, and the one who seems more fundamentally cut out for a life of crime, but he’s also more compassionate when dealing with people one-on-one, and his outlook regarding the long-term prospects for the club is ultimately more realistic. These internal and interfraternal tensions play out in all sorts of interesting ways. For all Smoke’s emotional investment in making a go of their speakeasy, for example, he also warns Sammie that he’s never known a musician who ended up happy. And there’s a nifty moment when Stack teaches a teenaged girl to haggle after he hires her to stand guard for a while over his truck full of pilfered mob booze, and she uncritically accepts his first-bid payment offer. Smoke might have let the girl make a sucker of herself, but that’s not how Stack rolls. Intriguingly, Michael B. Jordan makes very little visible effort to distinguish the two brothers in his performances, mostly letting the dialogue and situations do that for him. That sounds on its face like a sub-optimal choice, but it’s fitting in context, because the twins’ almost uncanny mutual similarity makes them a relatively benign reflection of the vampires, with their shared memories and blurred identities.

It’s Sammie, though, who gets the most powerful and thought-provoking moment of interaction with the undead. During the climactic battle, the boy finds himself at one point in Remmick’s clutches, facing seemingly certain death. And like the preacher’s son that he is, Sammie begins reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Experienced vampire movie aficionados will be expecting Remmick to recoil and release his prey, but that isn’t what happens. Instead, the vampire pauses in his attack to join Sammie in his recitation! Then at “Amen,” Remmick says to Sammie with a Gordian knot of emotion in his voice, “I hate the man who taught me those words, yet the words still bring comfort.” Suddenly it’s Jedidiah standing as the vampire’s reflection, trying to salve the wounds of oppression with the oppressor’s own balm, but lacking Remmick’s centuries of experience to teach him the futility of doing so. I always admire a writer who’s willing to let the villains speak important truths, and given the rest of Sinners’ themes, this one’s a doozey. The same goes for Coogler’s acknowledgement of the grim but genuine brotherhood to be found in banding together to harm somebody. Vampire, Klansman, or gang-banger (and the latter becomes relevant, too, before this movie wraps itself up at last!), they who respond to being on the outside by taking and destroying may find as much meaning and solace in doing so as the builders and nurturers of alternative communities, even if the meaning is monstrous and the solace diseased. Sinners recognizes that any attempt to overcome such despoilers, whether in fantasy or in the real world, must be ready to reckon with the allure of the pack-predator lifestyle.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact