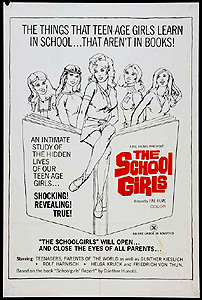

The School Girls / Schoolgirl Report / Schoolgirl Report, Volume 1: What Parents Don’t Think Is Possible / Confessions of a Sixth-Form Girl / Schulmädchen-Report: Was Eltern Nicht für Möglich Halten (1970/1972) ***

The School Girls / Schoolgirl Report / Schoolgirl Report, Volume 1: What Parents Don’t Think Is Possible / Confessions of a Sixth-Form Girl / Schulmädchen-Report: Was Eltern Nicht für Möglich Halten (1970/1972) ***

There’s a long tradition in the erotica business of dressing up porn as something else more respectable. Like, I can’t be the only person who ever looked at Michelangelo’s David and thought, “Huh. You know, I really don’t remember the verse in I Samuel that praises the shapeliness of the young King David’s junk.” In Europe during the 1970’s, the unapologetic raunch that characterized American porno movies was comparatively rare, and each nation seemed to have its own preferred disguise in which to cloak its cinematic smut. British pornographers favored comedy, of both the “elevated” satire-of-manners variety and the lowbrow music-hall variety. French porn tended to masquerade as Art. The Italians, as in all things, were content to adopt whatever approach was most profitable at the moment, only in grittier and more extreme form. West German porn had probably the most idiosyncratic cover story of all, though. In West Germany, porn posed as social science!

I’m not talking about all West German porn, of course. There were German sex farces, and smutty German coming-of-age melodramas, and films about sexually frustrated German housewives taking their lives in hand by means of a therapeutic affair or two dozen. But the genre that German pornographers made truly their own was the Sexposé. Teutonic cousins of the Italian Mondo movies, these films purported to chart the progress of the Sexual Revolution through various segments of West German society. Their technique was to mix dramatizations of supposed case studies with seemingly authentic woman-in-the-street interview segments, generally focusing on a single demographic group or social milieu. The educational pose was a longstanding ploy for outsmarting the censors, of course, but there was something different about how that pose was struck in 70’s Germany. At least at first, German Sexposés were shockingly sincere in their efforts to edify, and even more shockingly sympathetic to the cause of reforming the nation’s notions of sexual morality. They might trade on salaciousness, but the Sexposés were not half as cynical as most social-issues exploitation movies.

That’s doubly surprising, because the man most responsible for creating the Sexposé was producer Wolf C. Hartwig. Hartwig was a hardened veteran of the trash movie industry by 1970, having at least dabbled in practically every style and genre of interest to German audiences that his limited resources would allow. He made Krimis, spy movies, Westerns, exotic adventure films, counterculture exploitation pieces, deliriously strange horror flicks, and so on, frequently with a pronounced streak of sexploitation. The usual career trajectory for such figures would lead one to expect nothing but the basest of motives and the most shameless hucksterism so late in his professional development, but Hartwig turned out to be a little more complex than that. Not that his motives weren’t base, or his hucksterism not shameless, but when Hartwig handed over 30,000 marks for the film rights to sexologist Günther Hunold’s Schoolgirl Report— a book whose contemporary impact in Germany was comparable to that of the works of William Masters and Virginia Johnson in the English-speaking world— he didn’t just plaster its title onto any old piece of scummy grindhouse fare. The film version directed by Ernst Hofbauer and written by Günther Heller (which played in American adults-only theaters as The School Girls two years later) is remarkably faithful to Hunold’s perspective and intentions; it’s practically the polar opposite of what happened when Paramount Pictures bought the rights to make a movie of Alex Comfort’s The Joy of Sex.

The School Girls differentiates itself from the Mondo movies almost immediately by creating an overarching narrative context for its documentary and pseudo-documentary elements. During a field trip to the local power plant, eighteen-year-old Renate Wolf sneaks away from her class to have sex with the school bus driver, with whom she’s been having an affair for six months. (The opening credits include a notation for “many anonymous teenagers,” and they’re not kidding about the “anonymous” part. I’ve been unable to discover who played many of the key roles, Renate and her clandestine older boyfriend included.) This time, they’re caught in mid-screw by Dr. Vogt the physics teacher (Helga Kruck, of Girls in Trouble), and soon Renate is being forced to account for her conduct to the principal (Wolf Karnisch, from Sex in the Office and The Resort Girls) under threat of expulsion. When she fails to grovel before her elders in the prescribed manner, the expulsion proceedings move on to the next phase, in which the question is taken up at a meeting of the school’s Parents’ Association. At first, the meeting is basically a big slut-shaming party, with the parents angrily sounding off about the disgraceful example that filthy whore Renate is setting for their own, obviously angelic, youngsters. But then school psychologist Dr. Bernauer (Günther Kieslich, of Swinging Wives and Teenage Games) stands up. Bernauer contends that the principal, Vogt, and the parents have it all wrong. Their traditional morals might have served well enough in the authoritarian Good Old Days, but this is 1970. Kids today are better educated than ever before, trained to think critically and to analyze what they see and hear. “Because I said so” and “because we’ve always done it this way” aren’t good enough justifications in their eyes, and rightly so. Furthermore, this generation is the first in German history that has never known any form of government but liberal democracy, with its values of personal liberty and self-determination. In constructing their own sexual morality from the ground up, they’re doing nothing more than to apply those principles to the concerns that weigh heaviest on their lives. You see, Bernauer’s been conducting a study…

At this point, The School Girls becomes a series of more or less self-contained vignettes in which the other girls from Renate’s high school reveal how they navigate the treacherous shoals of sexual awakening without recourse to the ready-made answers accepted so uncritically by their parents’ generation. Heike (Jutta Speidel, of Spare Parts and Teenage Sex Report) attempts to get a rise out of her hunky young priest (Tonio von der Meden, from Boarding School and Secrets of Sweet Sixteen) with a sexually explicit confession. Susanne (Lisa Fitz) is in love with the college boy who tutors her in literature. Elizabeth Holm has chronic difficulties with her strict and conservative parents (Peter Dornseif and Ruth Küllenberg, the latter of whom was also in Campus Swingers and Varsity Playthings), but the shit really hits the fan when Mom catches her masturbating. Claudia (Mascha Rabben, from World on a Wire and The Sensuous Three), Karin, and Margit (Don’t Get Your Knickers in a Twist’s Marion Haberl) put the moves on Theo the swimming pool attendant (Gernot Möhner, of Love Under 17 and The Naked Countess), but the fun and games stop when Claudia learns that she’s pregnant. Hannelore and Herma (Waltraud Schaeffer, from Private School Girls and Secrets in the Dark) sneak into a construction site after the workers have gone home for the day in order to rendezvous with the equally inexperienced boys who have agreed to divest them of their virginity. And Lilo (Claudia Höll, of The Disciplined Woman and Soft Shoulders, Sharp Curves) wants to sleep with her dickhead boyfriend, Axel (Alexander Miller, from Bottoms Up! and Has Anybody Seen My Pants?), but needs help working up the nerve; her best friend, Irma, tries to put things into perspective for her by detailing her own rather astonishing career of sexual adventures and misadventures. Interspersed amid the aforementioned brief episodes are genuine documentary segments in which an interviewer who is supposed to be Dr. Bernauer’s assistant (Friedrich von Thun) accosts random young women on the street to ask them intrusive questions about their sex lives and attitudes toward same.

Those interview segments are a surprisingly large part of what makes The School Girls work. After all, the early 70’s were genuinely transformative times for nearly all Western societies, and although it’s true that all of the era’s sex movies shed light on those transformations simply by existing, it’s something else altogether to have one directly ask us to ponder the subject. If nothing else, the pretense toward sociology that the interviews represent cues us to look extra-hard at the dramatic portions of the film for clues to adult Germans’ thinking about sex circa 1970. (For example, I get the distinct impression that nobody back then was much troubled over the prospect of teenaged girls dating men well into their 20’s.) I’m sure the interviews were cherry-picked for shock value to at least some extent, but they still present a plausibly broad range of attitudes and opinions, and the filmmakers wisely left in a few instances when the subject found a question too personal to answer. (No outright refusals to speak for the camera, though.) Having the interviews around also bolsters the illusion that the “case studies” aren’t just some bullshit that Günther Heller made up, even if that’s probably exactly what they are. The effect is basically, “Listen to what this girl thinks about casual, recreational sex; now let’s see how those attitudes might play out in practice.” Most of all, though, the switching back and forth between fiction and nonfiction establishes The School Girls as something distinct from porn as we mostly know it today. By current standards, it’s downright abnormal for a skin flick to offer parenting advice, to plead for tolerance and understanding, or indeed to advocate overtly for any halfway coherent value system at all. By taking what amounts to a political position, The School Girls interestingly defies a genre rule that I’m usually not consciously aware of: porn shalt not preach.

As odd as The School Girls may seem to modern American viewers, its melding of titillation and polemic was not without precedent in Germany. It’s just that to find that precedent, you have to go all the way back to the late 1910’s and early 1920’s, to the roiling vortex of cultural (and sexual) experimentation that the country became following the collapse of the Kaiserreich at the end of World War I. There were luridly earnest documentary and pseudo-documentary films about changing sexual mores then, too, known as Aufklärungsfilme, or “enlightenment films.” They covered a huge range of formerly taboo topics— prostitution, abortion, venereal disease, homosexuality, etc.— and although it was the lure of the forbidden that got people in the door, the movies themselves advocated liberalizing reform with a crusader’s zeal. As you might imagine, they were not much loved by the Nazis, who turned them into fuel for public bonfires every chance they got after they came to power in 1933. Consequently, barely any of the original enlightenment films survive today, and they would have been but a memory even by the time Hartwig (born, like the Weimar Republic itself, in 1919) came of age. It’s hard to say, then, whether Hartwig realized what he was resurrecting with The School Girls. We can be reasonably sure that he never saw Diary of a Lost Girl, Prostitution, Different from the Others, or any of the Let There Be Light! pictures himself, but he could certainly have heard all about them from his older colleagues. But regardless, resurrecting the enlightenment film is pretty much what The School Girls did. It proved so explosively successful that Hartwig would make no fewer than a dozen sequels by 1980, together with a panoply of other “report” Sexposés: New Hot Sex Report, Nurses Report, Vacation Report, St. Pauli Report. Meanwhile, other producers weighed in with Student Report, Housewives Report, Virgin Report, Wedding Night Report, Girl Apprentice Report, and who the hell knows what else. I’m sure I’ll tire of the formula eventually, but right now, I’m eager to seek out a whole bunch more of these things.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact