Santa Claus (1959) -***½

Santa Claus (1959) -***½

Rene Cardona’s Santa Claus will make a lot more sense if you understand that Santa doesn’t figure in traditional Mexican Christmas lore. And really, why should he? Santa Claus, like his cousins and ancestors, Sinterklaas, Father Christmas, Grandfather Frost, Tomte, and the Christmas Goat, is an outgrowth of Northern European folklore related to pagan mid-winter festivals. In a land of harsh and ecologically unproductive winters, the solstice marks the bottoming out of a potentially deadly season; as the shortest day of the year, it’s like a promise from the cosmos that winter will stop getting worse, and that the spring thaw is on its way. Consequently, Europe’s pre-Christian solstice holidays almost invariably involved gift-giving as a token of faith in the coming end of winter scarcity, and it was natural for that spirit of generosity to find personification in some supernatural character. When Christianity co-opted the heathen solstice celebrations and redefined them as a birthday party for Jesus, it was similarly natural to co-opt the accompanying magical gift-givers by associating them with a theologically acceptable figure like St. Nicholas of Myra (a 4th-century bishop and signatory of the original Nicene Creed, legendary for stealthy acts of generosity) or St. Basil the Great (an early Christian theologian who lavished most of his huge family inheritance on the poor). It was not Northern Europeans who colonized Mexico, however, and the ceremonial god-eating practiced by the Aztecs on the winter solstice bore little resemblance to the Germanic Yule or the Roman Saturnalia. Christmas in Mexico therefore took a very different form, and while gift-giving was part of the mix, it traditionally happened on January 6th, in commemoration of the tribute paid to the Christ-child by the magi from the east.

Mind you, that was all before modern mass media turned American pop culture into one of the most powerful social forces in the world. By the 1950’s, gringo Christmas had begun to take root among the cosmopolitans of Mexico City, even if it took much longer to affect practices in the rest of the country. However, American Christmas traditions made their inroads in a very fragmentary way— Coca-Cola advertisements featuring the image of Santa Claus, references to Santa or his attributes in popular songs, that sort of thing. Mexicans, in other words, had discovered the idea of Santa Claus, but they understood him only a little better than Americans today understand the Day of the Dead.

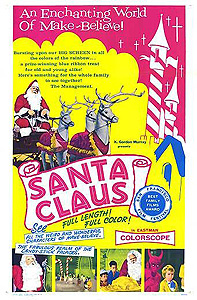

Still, the appeal of Santa Claus for children was unmistakable, and Mexican filmmakers in the late 1950’s were very much in the market for things that appealed to kids. The catalyst for the sudden, intense interest in kiddie flicks was Rene Cardona’s Tom Thumb, which had rather unexpectedly become a runaway hit in 1957, even to the extent of attracting attention from distributors north of the border. Cardona had made Tom Thumb outside of his usual partnership with producer Guillermo Calderon, and Calderon was understandably eager to have him try again within it. Meanwhile, Calderon and Cardona had lately enjoyed a different sort of unexpected boon. Florida-based entrepreneur K. Gordon Murray had not only learned of their work, but had been sufficiently impressed by it to become a reliable importer of their films. We’re not talking about a huge amount of money changing hands, of course, but American chump change went a lot further in Mexico. With Murray onboard, it made sense to start thinking about transnational marketability, and suddenly a synergy seemed to present itself. Mexican kids newly exposed to Santa Claus; American kids newly exposed to Mexican fantasy films— didn’t that add up to two countries’ worth of children whom Cardona, Calderon, and Murray could interest in a Mexican fantasy film about Santa Claus? There’s something touchingly naïve about that plan, and much the same could be said of the resulting movie, too. But naïve or not, Santa Claus was an enormous hit on its home turf, playing for seven weeks in an era of thrice-weekly program changes, and it made Murray a decent profit, too. In its first American go-round, Santa Claus played only in a few carefully chosen venues, but its performance was such that Murray would recirculate it on a wider basis every December for years to come.

The success of Santa Claus in the US actually interests me more than the reception it got in its native land, because American children (unlike their Mexican counterparts) were intimately familiar with Santa, and Cardona’s version of him is intensely weird. The story that Cardona and co-writer Adolfo Torres Portillo built around him, meanwhile, is weirder still. To begin with, this Santa Claus (Jose Elias Moreno, from Night of the Bloody Apes and The She-Wolf) doesn’t live at the North Pole; he lives in a magic castle in outer space, orbiting above the North Pole. Instead of elves, his Toyland factory is staffed by children from all over the world. If we can judge by some of the things said by their apparent leader, a little Mexican boy named Pedro (Cesareo Quezadas, of Tom Thumb and Little Red Riding Hood and the Monsters), these children have no knowledge of how things are done on Earth, which would have to mean that they were, like, changeling abductees or something. The reindeer who pull Santa’s sleigh are not living animals, but creepy-as-hell automata whose animatronic laughter could freeze the blood of an Ozian flying monkey. And he has as his roommates none other than Merlin the magician (Armando Arriola, from The Phantom of the Red House and The Skeleton of Mrs. Morales) and Vulcan the smith-god (Angel Di Stefani, of The Panther Women and The Aztec Mummy). They’re the ones who outfit Santa with the magical paraphernalia that enables him to reverse-burglarize everybody’s houses on Christmas Eve: the sleeping powder, the flower of invisibility, the universal key that gains him access to houses without chimneys. I assume that Merlin and Vulcan also constructed the devices whereby Santa keeps tabs on the naughty and the nice. Forget making a list and checking it twice— in this modern age, the benign totalitarianism of Good St. Nick requires the very latest in magical technology! Santa’s observatory is equipped with an all-seeing telescope, an all-hearing passive sonar array, and a global-range dream-peeper, all linked up to a talking computer even more terrifying than those fucking reindeer.

Santa has something else, too, that we don’t normally think of here in el Norte— enemies, and extremely powerful enemies at that. When you look closely at it, Santa’s job description basically makes him the truant officer of the cosmos. By punishing bad behavior and rewarding good with his annual toy giveaway, he helps police the morality of children who lack the sophistication to do what’s right simply because it is right. Who could object to that, you ask? How about Satan? For centuries now, Santa Claus has been leading ethically malleable children out of damnation, and the Prince of Darkness is thoroughly sick of it. This Christmas is going to be different. This Christmas, Lucifer is sending his minion, Pitch (House of Terror’s Jose Luis Aguirre), to Earth on a mission to tempt each and every child personally, with the object of producing an outpouring of juvenile evil the likes of which the mortal world has never seen!

Obviously this would be a long and unwieldy movie if we had to watch Pitch tempting all the world’s kids, so we’ll be limiting our give-a-fucks to just five, all of them residing in Mexico City. One of these is Lupita (Lupita Quezadas, Cesareo’s real-life sister), whose parents are too poor to buy her any toys. Another is a rich boy (Antonio Diaz Conde Jr.) who has all the material possessions any kid could want, but is chronically starved for parental affection. The rest are three beastly little brothers (your guess as to who plays them is as good as mine) who have yet to meet a Deadly Sin that they can’t get behind. (Just wait ‘til they find out about Lust in a few years…) Naturally, the latter trio are easy prey for Pitch. In fact, the devil will actually figure out how to make them aid him in his anti-Santa activities. You see, Pitch has made a connection that seems to have eluded his master thus far. Santa’s usefulness to the forces of cosmic good stems from his gift-giving to children who obey their elders, and his denial of gifts to those who don’t, right? So doesn’t it follow that if Pitch can prevent Santa from rewarding the good, then the whole scheme will be discredited, and evil will win the hearts of a sullen and disaffected generation?

Leave it to the filmmakers of an arch-Catholic nation to parse the theological implications of Santa Claus in a matinee kiddie flick, and to make it look effortless while they’re at it. Of all the mind-blowing things about this shoddy, silly, occasionally horrifying, frequently nit-witted trifle, that’s the one that makes me spend the longest time picking up the post-mindblow pieces. Cardona and Portillo’s Santa Claus may be just barely recognizable as our Santa Claus, but he makes eerily perfect sense in the context of Mexico’s far less pagan Christmas traditions. We gringos may marvel at the notion of Santa vs. Satan, but the logic is weirdly irresistible when you detach the character of Santa Claus from the folklore that limits him to embodying holiday generosity and cheer. After all, who else but the Devil would naturally stand opposed to Saint Nicholas?

Similarly irresistible, on close examination, is the logic behind many of the new attributes that the screenwriters have invented for Santa Claus. Most figures of folklore have powers or abilities that go unquestioned by people brought up with them. Americans raised with Santa might never think to ask how he does his work in such total secrecy, or how he acquires his knowledge of who’s been bad or good. An outsider, though, is likely to wonder exactly such things, and to consider “He just does” an unsatisfactory answer. Thus in Santa Claus we have sleeping powder, a flower of invisibility, and a magic key; we have panoptic sensory apparatus to monitor the deeds, words, and even dreams of all the world’s children; and we have auxiliary figures who could create such things for Santa, in case his own skill as a toymaker seems not quite equal to the task.

Of course, none of that does anything to change the impression of overwhelming screwiness that Santa Claus will almost certainly make with American viewers. I mean, the movie has a dance number set in Hell. It opens with a seemingly endless musical tour of Santa’s outer space child labor sweatshop. Lupita, under Pitch’s influence, has one of the most authentically nightmarish movie nightmares I can ever recall having seen, in which a chorus line of huge, menacing, Janus-headed dolls try to badger her into becoming a thief. The production design for Santa’s castle has much the same unsettling mix of cuteness and wrongness that famously characterized “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” 30 years later. And throughout, there are all the myriad ways, both great and small, that this is simply not the Santa Claus we know. It’s an uncanny effect that is all the more disturbing because the filmmakers didn’t set out to create it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact