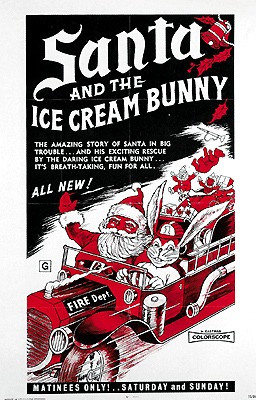

Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny (1972) -*½

Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny (1972) -*½

Most people, upon hearing the term, “theme park,” will think immediately of the ones that comprise the true core of the Walt Disney corporate empire. That’s perfectly understandable— especially today, when the Disney parks are far and away the most visible ones still in business. Historically speaking, though, it isn’t at all normal for a theme park to be that big or well-funded, and still less for one to be an international-scale tourist destination. Theme parks, more often than not, used to be shoddy, janky things with rickety rides, off-the-shelf carnival games, and mascot characters drawn straight from the public domain. Admission and amusements alike were cheap, and the intended customer base was a mix of locals looking to waste a summer’s day on corn dogs and roller coasters, and road-trippers in search of an enlivening respite from some miserable three-day drive. They rarely had their own hotels on the premises, and those that did sure as shit didn’t try to make them into gamified luxury “experiences” that would compete for time and attention with the park itself. And what’s more, you didn’t have to go far to find theme parks of this breed. They were scattered like pimples of erupting tackiness all over the American landscape. We even had one around here, about half an hour west of Baltimore; it was called the Enchanted Forest, and it incredibly remained a going concern until 1995. But the also-ran park we’re here to talk about today was located way down south, in the outermost orbit of Miami. It was called Pirates World, and it was among the first old-school theme parks to be crushed beneath the wheels of the Disney juggernaut.

The story of Pirates World began in 1963, when a Texan named C.T. Robertson abandoned the oil and real estate businesses in which he had made his fortune, and moved to Fort Lauderdale. The first thing Robertson did there was to buy an insurance company based in far-off Orlando, but that was merely because he needed a steady, practical, sensible source of income in order pursue a dream that wasn’t any of those things. Robertson wanted to run an amusement park that would not merely compete with Disneyland, but considerably exceed it in scale and ambition. Along with the expected thrill rides, vendor stalls, and carnival games, Robertson’s park would also incorporate a movie studio, a golf course, and a sports arena, all served by a luxury hotel. With that in mind, he acquired 100 acres of property in nearby Dania Beach, and hired Bob Minick, a former Disneyland employee who had gone on to do design work for Six Flags, Busch Gardens California, and the 1964 New York World’s Fair, to devise a plan for the site. What Minick came up with was Pirates World, 30-some acres of canal-riven land (plus another 30 acres for parking, and 30-some more for future expansion) subdivided into sections inspired by famous hotbeds of historic buccaneering: the Spanish Main, the China Seas, the Barbary Coast, etc. Customers who didn’t feel like walking would be ferried about the park on a galleon built originally for the 1942 Heddy Lamarr vehicle, White Cargo. Robertson and Minick even dared to hope that they could enlarge upon the theme by seducing the Pittsburgh Pirates into using their proposed stadium as the venue for their spring training sessions!

In fact, very little turned out quite the way Robertson, Minick, and their investors imagined. For starters, construction costs soared to $7 million— a 75% increase over the $4 million initially envisioned. That Hollywood galleon, meanwhile, foundered in transit, forcing the park owners to build a pirate ship their own. Indeed, the whole pirate theme degenerated rapidly, as Robertson tried to contain the burgeoning cost overruns by buying secondhand rides and attractions from Coney Island, an amusement park near Dayton (where one of the main Pirates World investors was based), and the aforementioned New York World’s Fair, the grounds of which were being dismantled as Pirates World was coming together. Robertson might rebrand the Belgian Aerial Tower as the Crow’s Nest (after the masthead lookout platforms on sailing ships), but there was nothing obviously nautical about a humongous steel gantry for hoisting spectator pods aloft on cranes. Nearby communities sued, alleging zoning irregularities, and complaining that proximity to the park would ruin local property values. Issues arose with the city government over sewer lines and inspection certificates for the rides, which ended up accounting for a much bigger share of the park’s productive land area than Minick had intended. There would be recurring squabbles with both county and state over taxes, which Robertson’s company, the Recreational Corporation of America, developed a habit of treating as an optional expense. The hotel and the golf course fell by the wayside, and the Pittsburgh Pirates never played a single inning on the grounds. Nevertheless, Pirates World was a genuine success in its early years of operation, at least with regard to the parts that were actually built. The secret, no doubt, was the park’s innovative all-inclusive pricing structure. There were no tickets sold inside Pirates World for rides, games, shows, parking, or anything else; the $3.50 admission fee got you everything but food and souvenirs.

Of course, when American businessmen are successful, they usually take that as their cue to expand their operations until they collapse under their own weight, and that’s just what Robertson did. Although he never built a stadium on the premises, he did put up an amphitheater in 1968. And when a battle of the bands for local rock groups the following year turned into one of the most profitable single days in Pirates World’s history thus far, he hired a promoter to lure in ever bigger and more popular rock-and-rollers to play on the amphitheater’s stage. Those shows charged admission separately from the rest of the park, but because they still occurred on Pirates World property, they transformed the establishment’s reputation in Dania Beach almost overnight. Henceforth, the park’s neighbors would see Pirates World as a gigantic homing beacon for shaggy, unkempt, pot-smoking no-goodniks, and the situation would only worsen as the concert venue consumed more and more of Robertson’s attention and resources, while the park proper fell into disrepair and dilapidation. By the time the local government put its foot down and stopped the music, there was no longer enough revenue coming in on the theme park side to withstand competition from the newly opened Walt Disney World. Sources conflict as to when exactly the end came, but it was no later than 1975, and might have been as early as 1973.

But let’s back up a moment, to 1968. The amphitheater wasn’t the only improvement that Robertson made that year to Pirates World, you see. He also went ahead and opened that movie studio which he’d been fantasizing about since the inception of the project. In one sense, R&S Film Enterprises truly exemplified the grand ambition of the original Pirates World concept, because the plan was to crank out five feature-length films each year, all of them aimed at the emerging kiddie matinee circuit. On the other hand, most of the films in question never got made, and the ones that did turned out impossibly cheap and shoddy. Also, the man on whom Robertson relied as the R&S house director was, of all people, Florida’s foremost softcore pornographer, Barry Mahon. If you thought Mahon ran low on give-a-fucks when he was catering to the raincoaters with the likes of Pagan Island and The Diary of Knockers McCalla, just wait ’til you see what he did with L. Frank Baum and Hans Christian Andersen! Mind you, Mahon wasn’t the only filmmaker to ply his trade at the Pirates World studio, which brings me to Richard Winer. Largely and deservedly unknown, Winer directed just two films. One, The Devil’s Triangle, was a fairly routine entry in the bullshit documentary genre which loomed so large in the 1970’s, but there was nothing routine about Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny. The final film produced at Pirates World, Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny is among the most improbably misbegotten pieces of children’s entertainment I’ve ever laid eyes on. Its every second is predicated upon the assumption that kids lack even the most rudimentary concepts of technical or artistic quality, and will contentedly watch any fucking thing at all. I suppose that’s true in a lot of cases, but rarely has juvenile non-discernment ever been leaned on as cynically as it was in this movie.

It’s December 21st, and the elves of the North Pole are hard at work assembling toys for all the world’s children. Something isn’t right, though, because Santa Claus himself (Jay Clark— who may be the same person as B-Western regular Jay Ripley underneath that lousy fake beard, but who would ever really know?) hasn’t yet returned from his annual global reconnaissance to assess the net naughtiness and niceness of all the kids on his list. That’s a worrisome state of affairs, because it’s way too late in the year for dilly-dallying or slacking off. Worse yet, the lead elf (Kim Nicholas, of Impulse) observes that the reindeer have come back— so where are Santa and his flying sleigh?

Would you believe they’re stuck on a dismal beach in southeastern Florida, inextricably mired in the ocean-damp sand? Evidently Good Saint Nick set his sleigh down too hard when he landed to give his reindeer a rest, and there seems to be no budging the vehicle now. Santa isn’t dressed for Florida, either, but he’s too wedded to keeping up appearances to shuck his snow suit and fur-lined hat while he searches for a way out of his fix. As the subtropical sun creeps ever higher in the sky, the old fool sings a superlatively lousy lament for his plight, and then passes out from heat exhaustion for what will be only the first of several times.

While Santa is unconscious, he somehow sends out a telepathic distress call to all nearby children, who drop whatever they were doing to rush to his aid. It says something about the care that Richard Winer put into Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny that the lineup of kids shown answering Kris Kringle’s psychic SOS is noticeably different from that of the group shown assembling on the beach with him immediately thereafter. Obviously no rabble of fourth-graders can match the pulling power of eight reindeer, but the kids are game to help in any way they can. Mostly that means fanning out to recruit every animal from the Pirates World petting zoo, but one enterprising girl contributes a man-in-a-suit gorilla to the cause! Alas, none of these scrawny beasts are up to the challenge, and despondency settles over the would-be rescuers. That’ll never do, so Santa Claus gathers the children together once again to hear an inspiring story— and a true story, if you can trust the Small God of benevolent home invasions…

What happens next depends on which edit of Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny you find. Usually Santa’s pep talk leads into a somewhat truncated version of Barry Mahon’s Thumbelina, but there’s also a chance that you might get a more drastic cut-down of his Jack and the Beanstalk instead. Either way, this irrelevant interlude consumes oodles of screen time, and neither insert is half as entertaining as, say, Rocket Attack U.S.A. You’re a thicker-skinned consumer of cinematic schlock than I if your blood doesn’t freeze at such a prospect. Regardless, the children are roused to redouble their efforts, but the real hero this day is a dog named Rebel, who high-tails it to Pirates World to summon the Ice Cream Bunny. Who? Nevermind that right now. The point is, the Ice Cream Bunny’s antique fire engine has range enough to take Santa all the way to the Pole, from which location he can apparently reclaim his sleigh by teleportation. Or something. I suppose. Okay— your guess is as good as mine.

By far the most baffling of this movie’s many mysteries is that Richard Winer acts as if we’re supposed to know already who and what the Ice Cream Bunny is. Note, by the way, that the creature’s on-film attributes have nothing whatso-fucking-ever to do with ice cream! My hypothesis is that if you had visited Pirates World in 1972, you might have encountered a grass-addled teenager in an ineffably horrifying lepiform mascot suit selling Fudgsicles and Drumsticks off the back of an old-timey fire truck. But dig though I have through several online compilations of Floridian Baby Boomers reminiscing about their long-ago visits to the park, I can find nothing that either confirms or refutes that notion. We may never know the true origin of this white-felt abomination or the nature of his arcane link to frozen desserts. All I can tell you with certainty is that he is an unclean thing, in a way that only cheap crap devised for the amusement of small children can be.

Another strange pair of guest stars are at least slightly easier to explain. The early efforts by the children of Dania Beach to free Santa’s sleigh from the grasping sand are peeped on from a distance by none other than Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. Mark Twain’s pre-teen troublemakers never contribute in the slightest to what passes for Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny’s story, however, and they disappear altogether until a final “Oh right— those guys!” reemergence just before the end of the film. What happened here was that Barry Mahon had tried to make a movie about the pair, but abandoned the project after a single day’s shooting. The few moments of Tom-and-Huck footage included here were all that Mahon had to show for that day’s labors, so no wonder he pulled the plug. You might still justly ask why Mahon’s Twain leftovers went into Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny specifically, but considering the scraps and garbage that comprise the whole rest of the movie, I concede that the fairer question is, “Why not?”

I simply cannot overemphasize what an absolute goddamned cheat Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny is. Regardless of which embedded Mahon reissue you get, the film contains barely more than half a hour of new material— and if you catch the 95-minute Thumbelina variant, that amounts to merely a third of the total running time! But of at least equal importance, literally nothing that occurs within those 30-odd minutes is remotely worth watching, except on some weird, masochistic meta level powered by simple incredulity in the face of the movie’s existence. The 21 minutes before Storytime consist of little but Santa Claus improvisationally muttering to himself like a homeless wino who just ran out of Thunderbird, while kids who have no idea what they’re supposed to be doing try to shove various uncooperative farm animals into the traces of his sleigh. And as if that weren’t enough, the whole segment is constructed backwards. Obviously the guy in the ape suit needs to be the climax, but in fact he’s the very first creature that tries and fails to move the sleigh.

Then in the post-insert wrap-up, the Ice Cream Bunny arrives as a pure deus ex machina, his existence never having been so much as hinted at previously. It’s disconcerting, too, that Winer never bothered to shoot the expected sub-Lassie scene in which Rebel would interrupt the Ice Cream Bunny in the midst of whatever Ice Cream Bunnies do in order to alert him to Santa’s predicament. One minute the dog is charging off down a dirt road into the rushes with the children at his heels, and the next minute some cotton-tailed monstrosity is driving a World War I-vintage fire truck out of Pirates World, the back of the vehicle loaded down with more little boys and girls than it could possibly carry safely. And of course the “race” to the rescue goes on unconscionably long, as the overburdened truck wheezes its way through the park, across the adjoining tidal swamp, and over the dunes to Santa’s crash site. There might have been some excuse for the dilation if anything exciting were going on— if Santa were in some kind of danger, say, or if the fire engine could manage more than five miles per hour between the terrain, the cargo hold full of unsecured children, and the obvious impossibility of seeing a fucking thing from inside the Ice Cream Bunny suit. Basically, Santa and the Ice Cream Bunny is only technically a movie. It’s a sequence of photographic images that seem to move when projected at 24 frames per second, and there are enough of them that it takes either 95 or 71 minutes to look at them all, but that’s just about all this travesty has going for it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact