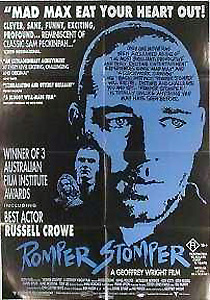

Romper Stomper (1992) *****

Romper Stomper (1992) *****

The past few decades have not been kind to taboos. The years since the late 1960’s have been a boom time for previously taboo subject matter in art and entertainment of all types, but the taboos themselves have, for that very reason, been in serious trouble. There are still a handful of subjects to which the popular media remain as allergic as ever, though, and violent, ideological racism is perhaps foremost among them. Movies, being the capital-intensive art form that they are, seem to be especially gun-shy on the subject of armed bigotry. With the kind of money that is involved in even the cheapest feature filmmaking on the line, who could blame a director, producer, or screenwriter from wanting to stay away from something so certain to make an audience uncomfortable? When organized racism does show up on the screen, it’s generally in a context like Mississippi Burning, where the focus is on either its victims or its opponents. Even American History X, which has a Nazi skinhead as its central character, is primarily about that character’s redemption through the renunciation of his old ways, and his efforts to prevent his little brother from falling too deeply into the same way of life. What you almost never see is a movie like Romper Stomper, which centers directly on a gang of neo-Nazis in Melbourne, but pointedly refrains from redeeming— or even explaining— them while simultaneously refusing the easy answers of caricatured demonization. It isn’t a film one watches lightly.

A trio of Vietnamese youths are riding their skateboards around Melbourne one night, when they take a fatal turn into a subway station that is a regular hangout of Hando (Virtuosity’s Russell Crowe, exuding considerable star power even at this early stage in his career) and his gang of skinhead hooligans. While his friends seize the immigrant girl and one of her companions, Hando takes the other boy aside and asks him what he’s doing “here.” The kid thinks Hando’s talking about the subway station, but Hando has a rather more general meaning in mind. “I want you to listen to me very, very closely,” he says, as coolly and collectedly as you could ask for. “This is not your country.” Then he and his gang beat the two Vietnamese boys within an inch of their lives while two of their number force the girl to witness the savagery.

Over the next couple of scenes, writer/director Geoffrey Wright lets us know just how distressing an experience we’ve let ourselves in for, by revealing that Hando, Davey (Daniel Pollack), the rest of the subway sociopaths are going to be our main fucking characters. Shortly after beating up the three immigrants, they all head over to their favorite pub, where they attempt to hassle the owner about rumors they’ve heard that he “had some gooks in here” recently. He tells them that if they’ve got a problem with that, then it’s their problem, and goes back to selling drinks.

Elsewhere in the city, the morning thereafter, a middle-aged man called Martin (Next of Kin’s Alex Scott) arrives at a junkie’s flophouse in company with a burly, leather-jacketed sidekick. While the sidekick works over the junkie out in the living room, Martin goes deeper into the house until he comes face to face with a girl in her late teens named Gabrielle (Jacqueline McKenzie, of The Deep Blue Sea). Evidently these two used to live together, and from the way Martin lays his hand on Gabrielle’s breast, I’d say we’re looking at some kind of May-September romance thing here. Martin wants Gabrielle to come back to him. Living with a junkie is obviously no good for her, and there’s no way she can afford to keep herself supplied with the expensive medicine she (notionally) takes for her epilepsy if she’s got no household income but a pair of monthly welfare checks. Gabrielle agrees that the time has come to change her living arrangements, but she has no intention of moving back in with Martin. Instead, she just drifts around town for a while, until finally she ends up at the pub where the skinheads congregate. She attracts the attention of both Hando and Davey, and soon ends up as a hanger-on in such adventures as minor rampages of petty theft and vandalism and wild parties full of drinking, sex, and constant low-level violence. And though it’s Hando to whom Gabrielle is primarily drawn, it’s clear from the beginning that she would really be in better hands with Davey.

Things start to go sour for the neo-Nazis of Melbourne when the owner of their hangout sells the place to— that’s right— a Vietnamese restaurateur who wants to give his three sons an entryway into the business world. And by a particularly perverse twist of fate, the immigrant entrepreneur’s daughter happens to be the girl who was menaced by Hando’s gang in the opening scene. Reinforced by some friends from out of town, Hando and his cronies attack the new proprietors of the bar, but one of them is able to get away and fetch help. The tables are turned on the skins when seemingly every Vietnamese male in Melbourne between the ages of fifteen and thirty converges on the pub and counterattacks, overwhelming the fascists and pursuing them back to their warehouse squat. Hando and company aren’t safe even here, as their erstwhile victims lay siege to the squat. Only five of the skinheads escape as the Vietnamese set fire to the warehouse: Hando, Davey, Cackles (Daniel Wyllie, of The Roly Poly Man), Sonny (Leigh Russell), and the barely pubescent Bubs (James McKenna), along with Gabrielle and two other girls, Megan (The Ripper’s Josephine Keen) and Tracy (Samantha Bladon).

The first thing Hando’s much reduced gang is going to need is a new place to live. They get it by seizing control of another abandoned warehouse, forcing out its current stoner hippy occupants. Then the skinheads turn their attention to revenge. This isn’t going to be a matter of boots and bottles, either— Hando wants guns, but to get them, he’s going to need money neither he nor his followers have. This is where Gabrielle makes herself useful. While the guys sit around the table, wracking their brains as to which local establishment would be the most lucrative target for a robbery, she mentions that she knows of an extremely wealthy man, whose portable possessions would net them a fortune on the black market. She means Martin, of course. Gabrielle stops by to visit him the next night, and as soon as she has a chance to get out of the man’s sight, she unlocks the electronic gate outside his mansion, allowing Hando’s boys ingress. The skins beat Martin up, tie him to the toilet, and begin looting his house. While all that’s going on, Gabrielle enjoys a quiet moment alone with Davey, in which she lets on why she should hate Martin so much. While it’s true that he’s a drastically overage ex-boyfriend, he’s also a lot more than that. Martin is really Gabrielle’s father! No sooner has this bombshell been dropped, however, than Martin gets loose, and comes after his assailants with a gun. Hando and the skins are lucky enough to get out with their lives; the raid comes up entirely bust as a revenue-raising operation.

In the aftermath of their failure at Martin’s place, what’s left of Hando’s gang starts to come seriously unraveled. Megan and Tracy split when they realize that the boys are serious about killing the Vietnamese. Hando and Gabrielle have a falling out which leads to her leaving the squat and calling the police on the gang. A similar rift opens between Hando and Davey when the latter quits the gang to pursue a relationship with Gabrielle. And when the cops come in response to Gabrielle’s tip, the shit really hits the fan. Megan’s parting pronouncement that “You'll all end up fucked!” turns out to be right on the money.

Romper Stomper doesn’t pull any punches. It never flinches from depicting the brutality of the skinheads’ way of life, but at the same time, it refuses to moralize on the subject, and the lack of explicit condemnation sometimes comes uncomfortably close to feeling like approval. The only reason that’s so, however, is that we’ve come to expect so much hand-holding from movies that take on such explosive topics as neo-Nazism that it becomes disorienting when a filmmaker like Geoffrey Wright comes along and says in effect, “Here it is; do what you want with it.” Any pat response to Wright’s challenge is ruled out by his handling of the characters and their situation. Hando, though as repugnant a man as you could ever care to meet, has a certain undeniable charisma to him, and evinces a certitude and commitment regarding his beliefs that would be admirable were it not for the content of those convictions. In contrast, Davey, the most sympathetic of the skinheads, and the only one who has it in him to walk away from the gang, does so not because he rejects Hando’s ideology but merely out of attraction to Gabrielle. And when Hando later tries to convince Davey that Gabrielle isn’t worth his love, it’s difficult to argue with him. We are talking, after all, about the only girl in the gang’s orbit who was not troubled by the prospect of escalating the violence against their immigrant foes to lethal levels. The ultimate fate of the skinheads is no easier to come to grips with, morally speaking. When the Vietnamese immigrants retaliate against them at the pub, they are as uncompromisingly, mercilessly vicious as the skinheads themselves, and the cruelest destiny of all is reserved for the gang member who makes the nearest approach to innocence: Bubs, who at perhaps fourteen years of age is shielded by his elders from the worst of the violence, and whose entire involvement with Hando seems to be nothing more than the product of a misguided search for acceptance. There is, simply put, no one in this movie with whom the viewer can safely identify, but the caliber of the writing and acting is such that the urge to identify with somebody is all but irresistible. Romper Stomper will be far too harsh for many— indeed, most— audiences, but it’ll be a long time before anyone makes another movie this good about Nazi skinheads.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact