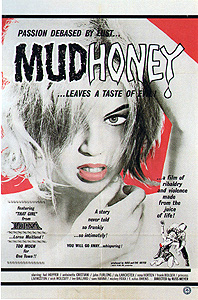

Mudhoney/Rope of Flesh/Rope of Love/Rope (1965) **

Mudhoney/Rope of Flesh/Rope of Love/Rope (1965) **

Mudhoney was the second of Russ Meyer’s “serious” movies. If the opening credits are to be believed, it was derived from a novel called Streets Paved with Gold, and the very fact that Mudhoney lays claim to a literary basis, however obscure, betokens a considerable enlargement of Meyer’s creative ambitions since the days of Eve and the Handyman and Heavenly Bodies. In many respects, this film can be seen as an expansion upon the themes Meyer explored (and exploited) in the somewhat earlier Lorna, for both pictures deal, in a markedly pessimistic manner, with the interpersonal havoc that ensues when a man with a criminal past inserts himself into a rancorously unhappy marriage. Mudhoney simply takes matters further by widening the playing field to encompass the troubled couple’s entire town.

In America at the middle of the 20th century, few things said, “I’m a serious artist now— no, really!” like setting your story in a small, rural village during the Great Depression. Meyer, wanting very badly at this point in his career to be taken for at least a potentially serious artist (if only in order to satisfy the “redeeming social value” standard that controlled the outcome of obscenity trials in the mid-1960’s), thus introduces us to Depression-ravaged Spooner, Missouri, where an ex-convict drifter called Calif McKinney (John Furlong, of Common Law Cabin and Supervixens) has paused on his route to the West Coast promised land for which his recently deceased mother named him. Calif’s first encounter in the struggling little hamlet is with Maggie Marie (Princess Livingston, from Wild Gals of the Naked West and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls) and her daughters, Eula (Fanny Hill’s Rena Horton) and Clara Belle (Lorna Maitland, from Lorna and Free, White, and 21). These women (demonstrating that Meyer’s newly minted membership card for Serious Artists’ Union Local 670 is almost certainly a forgery) are the proprietress and inmates respectively of the neighborhood brothel, and Eula in particular seems eager to give out some free samples of the specialty of the house upon meeting with the newcomer. Appealing though that prospect may be, Calif insists upon putting business before pleasure. He’s just about out of money (isn’t everybody these days?), and he hopes to score a job someplace as a farmhand or a handyman. Maggie Marie doesn’t have any land in need of tilling, and she’s already got a handyman in Clara Belle’s boyfriend, Injoys (Sam Hanna), so there isn’t much she personally can do for Calif. He could always try talking to Lute Wade (Stuart Lancaster, of Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! and The Long, Swift Sword of Siegfried), but the consensus among Spooner’s three ladies of the evening is that Calif would be better off moving on to the next settlement rather than seeking a job with Wade.

Lute himself isn’t the problem up at the Wade place, and neither, for that matter, is his niece, Hannah (Antoinette Christiani). No, what accounts for that farm’s unparalleled turnover rate among the hired help is Hannah’s husband, Sidney Brenshaw (Hal Hooper, another familiar face from the Lorna cast). Brenshaw has a drinking problem of Herculean proportions— and if you remember what Hercules is supposed to have done to his wife in a drunken rage, then you’ll understand that I use the term advisedly. He’s also a jealous, sadistic bully, and if there’s anything he likes better than beating and raping his wife once he has a few shots of rotgut corn liquor in him, it’s starting fights with people who are too dependent upon his good graces to fight back. Lute regards his nephew-in-law with undisguised loathing, and the feeling is more than mutual. However, Brenshaw is prevented from breaking openly with the older man by his powerful sense of self-interest— Lute owns the farm free and clear, and that much land is an enormously valuable asset in a time when other forms of wealth are in such short supply. Lute has nobody but his niece on whom to bequeath the family homestead, so Sidney means to bide his time until his wife receives her inheritance, at which point he can sell the farm, pocket the money, and run off to Kansas City a rich man (relatively speaking), leaving Hannah to fend for herself back home in Spooner. And since Wade remains a prodigiously hard worker despite both his age and his weak heart, Brenshaw figures he won’t have to bide his time very much longer.

Calif’s arrival on the scene complicates Sidney’s plan enormously. First of all, Lute takes an instant liking to Calif, and though the old man calls in some favors with his buddy, Sheriff Able (Nick Wolcuff, of Red Zone Cuba and Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers!), to check into the new farmhand’s background, he concludes swiftly enough that McKinney is an honest man now, whatever his previous misdeeds. Lute also perceives almost immediately the attraction that Calif and Hannah feel for each other, and he does whatever he can to give quiet encouragement to the pair while Sidney spends his evenings getting liquored up and enjoying the services of Eula and Clara Belle. But most importantly, Wade slyly rewrites his will as soon as he has satisfied himself of Calif’s reliability. Under the new terms, Hannah will not inherit the farm directly; rather, it will be held in trust for her, with management of that trust going to Calif. This maneuver cuts Brenshaw out of the action almost completely. Even if he were to kill Lute himself tomorrow, and even if he were to succeed completely in turning public opinion in Spooner against Calif and Hannah (would-be adulterers that they are) with the aid of the hypocritically sanctimonious preacher, Brother Hanson (Frank Bolger, from Eve and the Handyman and Cherry, Harry, and Raquel), he’d still have to spend the rest of his married life kissing the ass of his increasingly hated rival in order to maintain access to his wife’s modest riches. The trouble is, though, that men like Sidney Brenshaw are never more dangerous than when they figure out that they’ve lost…

Russ Meyer brought something rare and precious to the sexploitation genre. He was a natural-born cinematographer and film editor, with an eye for composition and a feel for pacing that few others in the business could match, and by the time he directed Mudhoney, he’d been honing both talents for more than twenty years. Mudhoney is simply one of the best-looking movies of its type that you’ll ever see. Unfortunately, the heavy emphasis on redeeming social value makes it a far less effective fusion of sex and violence than the 42nd Street roughies that were seeing release at roughly the same time on the opposite seaboard. The problem is that, however cynical his initial motive for tackling “serious” subject matter in a sex film, Meyer seems to have sincerely embraced the social value concept once it had been forced upon him. Mudhoney is trying to be two movies at once— an earnest Great Depression melodrama on the one hand, and a tacky T&A spectacle on the other— and the two aspects keep getting in each other’s way. Somebody like David Friedman might have enjoyed great success with a premise like, “It’s The Grapes of Wrath— except with boobies!” but Meyer expends too much effort in Mudhoney on trying to do right by the first element of that formula. Whenever the scene shifts to Maggie Marie’s whorehouse, or to the creek where Clara Belle likes to go skinny dipping, it feels like a piece of some other film has been Jerry Warrened in, and the movie invariably loses its footing for a bit. Furthermore, with a cast consisting solely of low-grade hams and women who were chosen mainly on the basis of their huge and pillowy breasts, Mudhoney just doesn’t have the thespian infrastructure to support the weightier dramatic material. It can’t be The Grapes of Wrath and it won’t be Poor White Trash, so instead it winds up being not much of anything.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact