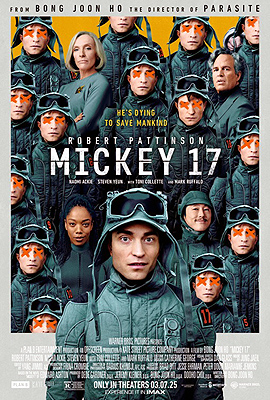

Mickey 17 (2025) ****

Mickey 17 (2025) ****

There’s a longstanding cliché which has it that outsiders to a culture are able to see it more clearly than those who were brought up within it. I don’t think I buy that as a general principle, but it certainly is true in one specific context: if you want to know what makes your culture weird, ask someone who wasn’t raised to think of the whole thing as normal. First in Snowpiercer, and now again in Mickey 17, South Korean writer/director Bong Joon Ho has proven himself an extremely perceptive observer of the grotesqueries and abnormalities in Western, and especially American, culture. Watching one of his satirical sci-fi movies is like seeing yourself reflected in the undulating glass of a funhouse mirror. Stretched, compressed, and distorted though the image may be, it’s unmistakably, undeniably us.

The year 2054 finds the Earth in the midst of a slow-rolling apocalypse that basically boils down to everything getting more and more like 2024 for the next three decades. Corporations have run amok, governments are too thoroughly captured by the billionaire caste to have much interest in stopping them, and although democracy still technically exists, any notion of it acting to steer the world’s leaders, rulers, and owners toward some vision of the common good is long forgotten. The result has been utter dysfunction in every domain, as the morbidly rich treat the entire planet the way private equity firms treat a business acquired with someone else’s money. For the regular Joe, the only ways to get ahead anymore range from the vaguely scammy to the openly criminal, and three years ago, Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson, from Twilight and The Rover) and his shady and opportunistic best friend, Timo (Steven Yeun, of Okja and Nope), got themselves caught at the intersection of both. The seed capital for their vaguely scammy startup came from notorious loan shark gangster Darius Blank (Ian Hanmore, from The Awakening and Dungeons & Dragons: Honor Among Thieves), and let’s just say that debts to crime lords are not dischargeable in bankruptcy. When the business failed, Mickey and Timo were left with no way to pay back the loan— and Darius Blank had a well-earned reputation for hounding his debtors to the literal ends of the Earth.

Luckily for them, however, there is in the 2050’s a way to go beyond the ends of the Earth for those with sufficient wealth, skill, connections, or good old-fashioned desperation to pursue it. Having thoroughly ruined this planet, the oligarchs have turned their attention toward other worlds altogether. One such would-be Master of the Universe is a right-populist politician, technology industrialist, and cult leader by the name of Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo, of Mirror, Mirror II: Raven Dance and The Dentist), who, having lost his latest election, has decided to go Galt on an inhospitably frigid planet aptly called Niflheim. When Barnes reaches the spaceport concourse to sign up for a slot on Marshall’s crew, he predictably finds most of the positions either already taken or defined by criteria he can’t possibly satisfy. There is one role available for which Mickey is fully qualified, though, and while he has no idea what in hell an “expendable” might be, he figures it has to be preferable to sticking around on Earth to be tortured to death by Blank and his agents.

Well, maybe. Arguably. Depending on how you look at it. As a more intelligent person than Barnes, with a better education and a richer vocabulary, might have surmised from the position title, Mickey has literally volunteered to be killed— and many of the ways to die on a three-year interstellar voyage are at least as torturous as anything Darius Blank could devise. And while Blank would have killed him just once, Mickey’s role on the voyage to Niflheim will require him to die over and over and over again. You see, there have been tremendous advances in both data storage and 3-D printing over the past 30 years. It’s now possible to map every cubic micron of a human body, to upload an entire human consciousness into a computer, and to leverage the resulting trove of information into a kind of serial immortality by synthesizing copies of the original person from suitable amounts of precisely formulated organic slurries (such as might be concocted by a starship’s waste-reclamation system). Thank super-genius psychopath Alan Manikova (played in explanatory flashbacks by Edward Davis), who developed the technology so that he could go on murder sprees in one body while establishing ironclad alibis in another. Unsurprisingly in light of its provenance, such human duplication has been illegal on Earth ever since, but offworld there’s little law beyond the whims of the CEO financing any given colonization effort. So whenever a need arises on the trip to Niflheim that will probably kill the person tasked with fulfilling it, it immediately becomes Mickey’s problem. Malfunctioning hardware that can be fixed only from outside the ship under bombardment by lethal levels of cosmic rays? Send Mickey. Virus of unknown symptoms and transmissibility infesting the air of the world to be colonized? Send Mickey. Vaccine that might or might not confer immunity against the germ in question? Give it to Mickey. All in all, Barnes has died sixteen times as of the moment when we join the action, and it looks like he’s in for yet another death in short order.

That’s because the virus that killed Mickey a few times after the colony ship made landfall isn’t Niflheim’s only indigenous organism. The planet is also home to a species of subterranean animal somewhat resembling a cross between a pillbug and a cuttlefish, ranging in size from that of a largish cat to that of a Greyhound bus. They’re powerful, well-armed, and dangerous when provoked, and on the exploratory sweep that first encountered them, a woman by the name of Jennifer Chilton (Ellen Robertson) did indeed provoke one. Barnes thus found himself with yet another miserable assignment: to capture a specimen of the “creepers,” however many times he had to die in order to do it. Ironically, though, it isn’t the creepers that seem likely to initiate the generation of Mickey 18, but rather Mickey 17’s own clumsiness. He fell down a hole in the ice while monster-hunting, and none of his companions on the foray can see any way to get him out of it that’s worth the risk and bother in comparison to just printing out one more copy. But no sooner do the rest of the team set off back home to the landing site than a whole swarm of creepers wriggle out of the ice at the bottom of the crevasse. Instead of devouring Barnes on the spot, however, the creatures carry him back to their lair, present him before a giant of their kind who seems to function approximately like a queen bee, and then lug him all the way to the other end of the cave system where they live to deposit him on the surface— not just totally unharmed, but within safe enough trudging distance of the colony ship. Huh. I wonder what that was about?

Answering that question is probably the most important thing that any human on Niflheim could be working on right now, but for the seventeenth incarnation of Mickey Barnes, it’ll take a back seat for a while to the fact that his bosses have indeed printed out the eighteenth by the time he returns. You remember how Alan Manikova invented his human-duplicating system in order to facilitate a side hustle as a serial killer? Well, evidently public opinion, missing the point as usual, settled on a notion that the killer copies of Manikova were driven to murder by some side effect of their simultaneous existence, rather than simply because their source personality was a psycho to begin with. Consequently, even on offworld colonies where artificial reincarnation is legal, multiplicity is not, and it’s furthermore punishable by the destruction of all extant copies of the person found gadding about in more than one body. Each of the two Mickeys therefore has an obvious incentive to eliminate the other one before anybody finds out about them, but neither 17 nor 18 is talented enough at murder to close the deal. Fortunately, all three of the people who catch on to Barnes’s xerographic mishap were in one way or another already his friends.

There’s Timo for starters, who incredibly managed to finagle his way onto Marshall’s ship independently of Mickey 1, and with a much better place in the pecking order. Mind you, Timo is no more trustworthy on Niflheim than he was back on Earth, but since he currently supplements his above-board income by dealing illegal drugs, he’s almost as susceptible to blackmail as his now-bifurcated old pal. Then there’s Mickey’s girlfriend, Nasha (Naomi Ackie, from Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker). No, really— he managed to get himself a girlfriend even despite his busy schedule of repeatedly dying and the social stigmas that go along with it, and what’s more, she’s one of the ship’s mercenary gendarmes! Granted, that job description would tend to pigeonhole Nasha as the last one in their personal lives whom the Mickeys would want to discover their secret, but it happens that she’s a bit of a pervert, and she recognizes at once the unique possibilities that two simultaneous instances of her lover present. And finally, there’s Kai Katz (The Empire’s Anamaria Vartolomeo), who was Jennifer Chilton’s girlfriend before the creepers got her. She got interested in Mickey because his intimate acquaintance with death seemed to offer the possibility of reaching some kind of acceptance of Jennifer’s, and since Kai swings both ways, she caught feelings for him over the course of their conversations on the experience of dying. That was a problem when there was just one Mickey, but now that there are two, she reckons that all parties should be satisfied if she claims Mickey 17 for herself while Nasha moves on with 18, which she was in the process of doing anyway.

It should be obvious at this point that both of Mickey’s lives are now extremely fucking complicated, but it’s about to get a whole lot worse. For one thing, Nasha doesn’t agree with Kai at all regarding the romantic allocation of his two identities, and the destructive capacity of women in jealous rages is literally proverbial. For another, it turns out that Timo purchased his ticket off of Earth at the expense of Mickey’s ass, and that Darius Blank’s reach extends all the way to Niflheim. But overshadowing even that is what happens when the colony’s mad CEO-king fortuitously gets his hands on a creeper without Mickey’s help, and decides to go to war with the creatures, at least in part because his only slightly less crazy wife (Toni Collette, of Stowaway and The Sixth Sense) thinks she might be able to make one of her worlds-famous sauces out of them. Mickey 17, as the only human to have fallen into the creepers’ clutches and lived, is thus an intelligence asset without peer for the plotters of culinary genocide— and simultaneously a diplomatic asset without peer for the furtive but growing faction of colonists who have decided at last that they’ve had enough of Kenneth Marshall.

Mickey 17 was based on a novel by Edward Ashton, entitled Mickey 7. As that ought to imply, the book’s protagonist is on merely his seventh incarnation when the story gets really rolling. The addition of ten more cartoonishly hideous deaths implies all by itself the main difference between Bong Joon Ho’s approach to the material and Ashton’s, for while Mickey 7 was certainly animated by satirical intent, Mickey 17 is blackly absurd from top to bottom. It’s a dark farce in which the jokes go off like explosions, not just because they’re boomingly un-subtle, but also because they’re full of sharp objects flying at lacerating speed. Since this is shaping up to be the Laugh to Keep from Screaming Century, I’d say Bong has the right idea.

This is a strangely constructed film, in ways that you might be able to glean from the above synopsis. Not only does Mickey 17 begin in media res, and use flashbacks to fill in the details of how we got to the starting point, but it overlays those flashbacks with oddly chatty explanatory narration by Mickey himself. Furthermore, the movie keeps derailing itself with additional flashbacks every time the present-day plotline bumps up against a new occasion for back-story. The overall effect is to make Barnes an even more vivid figure, turning narrative structure into a vehicle for character insight. Mickey isn’t very bright, so he isn’t a very adept storyteller, either. He tends to ramble, to lose his place, and to get distracted by the temptations of a tangent. In hands less skilled than Bong Joon Ho’s, this could become exasperating, but while Barnes is frequently not in control of his narrative, Bong unfailingly is. The digressive flashbacks create merely the illusion of scatterbrained babbling, for in fact they’re jam-packed with vital information expanding and deepening our understanding of Mickey’s two worlds, even when their relevance to the plot per se is questionable or temporarily obscure.

That’s important, because Mickey 17 belongs to the troublesome tradition of satirical sci-fi in which the details of the setting do more work than the events of the story. And the breadth of the movie’s satire is fully equal to the era of imbecile polycrisis in which we’ve all spent the last decade and change. Every element of the film is a dystopian exaggeration of some pernicious feature of the present day, from the anti-human application of the technological marvel at the premise’s core, to the anti-human law and politics governing its use, to the anti-human economics that make it possible to imagine someone accepting it as a condition of their employment. The queasily zany grotesques who populate the upper echelons of society in this fictional future are all recognizable composites of the queasily zany grotesques who rule the real world right now. Darius Blank is the next step up from the post-Soviet arch-gangsters who make Vladimir Putin’s tyranny possible on a day-to-day basis. Alan Manikova developing a potentially world-changing technology for no better reason than to murder without getting caught is a luridly blood-soaked enlargement of Mark Zuckerberg launching “The Facebook” (as it was called back then) as a platform for sexually harassing his Harvard classmates from a safe distance. And Kenneth Marshall is a garish amalgam of Donald Trump, Elon Musk, and Sun Myung Moon, married to an Imelda Marcos whose passion is nouvelle cuisine instead of designer shoes. It’s possible to see the latter two references as dated, but I’d argue that they’re meant to remind us that the raw material for the elite freakshow of the 21st century was always there, lying in wait on the fringes. After all, there’s a much more explicit nod to the continuity of authoritarian clownishness in the makeover that Marshall gives himself after declaring war on the creepers, modeled directly on Mussolini cribbing his public image from Bartolomeo Pagano. Never let it be said that Bong Joon Ho doesn’t do his homework.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact