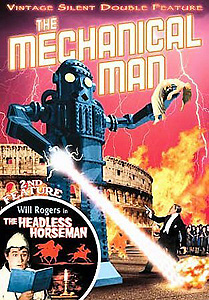

The Mechanical Man/L’Uomo Meccanico (1921— fragmentary print) [unratable]

The Mechanical Man/L’Uomo Meccanico (1921— fragmentary print) [unratable]

Czechoslovakian playwright Karel Čapek premiered his science-fiction drama, Rossum’s Universal Robots, in 1921, giving the world a new word for machines made in the image of man. Ironically, however, what springs to mind most immediately when one hears the word “robot” is almost nothing like what Čapek envisioned. His robots were artificial but completely biological people, rather along the lines of Blade Runner’s much later Replicants. It would take a few years for the semantic transformation to complete itself, meaning that one of the earliest known movies about a robot cannot be so described without committing a serious anachronism. Writer/director Andre Deed, better known for starring in a long-running series of slapstick comedy shorts, made The Mechanical Man the very same year that Rossum’s Universal Robots was first performed, and it understandably makes no use of Čapek’s neologism.

Or, at any rate, it doesn’t appear to. It’s hard to be really sure, though, because there isn’t a whole lot left of The Mechanical Man these days; indeed, it was long believed to be lost altogether. But then a few years ago, some 740 meters of fragments from a print with Portuguese-language intertitles were discovered in a studio archive in São Paolo. Italian censorship records indicate that The Mechanical Man originally ran to 1821 meters, so what turned up in Brazil accounts for roughly 40% of the picture’s total length, working out to about 26 minutes in the restoration now available on DVD from Alpha Video. Most of the surviving material appears to have come from the second half of the film, with a couple of very brief bits (running just a few seconds apiece) from earlier on. Ordinarily, this would make what’s left of The Mechanical Man extremely hard to follow, but the DVD fortunately begins with a synopsis extrapolated from contemporary reviews and advertising material.

According to that synopsis, a brilliant scientist invents a huge, remote-controlled mechanical man, possessed of tremendous strength and speed, and equipped with powerful electrical generators in its hands. Unfortunately for the scientist, his creation comes to the attention of a masked female arch-criminal named Mado (Valentina Frascaroli, from Maciste of the Alps), who with the help of her gang kills the inventor in a bid to steal the plans for the automaton for use in her upcoming reign of terror. Before she can make much headway on her big project, however, Mado is caught and brought to justice by Inspector Ramberti (Ferdinando Vivas-May). This is just a temporary setback for the villainess, though, for the ever-resourceful Mado escapes by setting a fire in the prison infirmary and sneaking away in the ensuing confusion. Then she kidnaps Elena D’Ara (Mathilde Lambert), the niece of the murdered scientist, with the aim of extracting from her the secret of the machine’s creation. Elena caves to Mado’s demands, Mado builds the automaton, and the reign of terror commences according to plan. Luckily, the dead inventor’s brother, Professor D’Ara (Gabriel Moreau, of Maciste’s Voyage and The Testament of Maciste), is also an accomplished scientist, and he constructs a second mechanical man to counter Mado’s. The two metal titans join battle at an opera house, where their struggle just about levels the building. Evenly matched, the machines fight each other to a standstill until Mado gets cooked to death by a malfunction of the electrical equipment whereby she controls her robot.

The Brazilian print starts off with what I take to be fragments of the scene in which the inventor puts the mechanical man through its paces, while Mado spies on the trials. Thus that inferred synopsis is almost immediately called into some question, for if the scientist has already built his robot, then you sort of have to wonder why Mado wouldn’t just steal the completed machine. Regardless, the print quickly skips ahead to Mado’s escape, then to what appears to be the lead-up to the kidnapping of Elena D’Ara, and once more to a fairly lengthy intact stretch in which Ramberti attacks the problem of both disappearances, initially arresting Elena’s idiot brother, Modestino (Deed himself, in a role essentially in keeping with his prior acting career), in connection with the girl’s disappearance. Mado herself comes to Ramberti’s aid by mailing him a taunting letter explaining all the details of her prison break, there’s a brief glimpse of a subplot in which Modestino apparently goes on the lam and hides out in the mountains with a Gypsy woman, and Elena rather mysteriously turns up not too much the worse for her captivity, neatly solving her brother’s legal troubles. Next comes a rather irritating comedy bit, in which Modestino takes Elena to a party at the home of Countess Marguerite Donatieff, but the clowning is thankfully nipped in the bud when Mado’s robot attacks the chateau. This is where things get really interesting (and where the film seems to become much less seriously plagued by lacunae), as the mechanical man attacks the D’Ara family at home, and is prevented from finishing off the lot of them only by an untimely short-circuit in the control equipment back at Mado’s lair. The police ride to the rescue, but Modestino mistakes them for Mado’s gang, and opens fire with his revolver; Ramberti and his cops are so busy arresting him again that they fail to notice the real Mado gang arriving to haul away their temporarily incapacitated super-weapon. Then, finally, comes the attack on the opera house, which occurs right in the middle of a masquerade party, allowing the mechanical man to sneak inside on the pretext of being a human in costume!

Basically, there’s just enough of The Mechanical Man here to make you really wish you could see the rest of it. The robot itself is very impressively realized for 1921, and despite Deed’s background in slapstick comedy, he treats the machine as a completely serious agent of menace except in the few minutes during which it poses as a guest at the opera house masquerade. Some have attributed the director’s evident commitment to the fantastic to the influence of Georges Méliès, of whom Deed is sometimes described as a protégé. This seems a rather odd claim, given that Deed has but one other directorial credit for anything save his usual goofball comedies— a short with the intriguing title, La Paura degli Aeromobili Nemici (“The Fear of the Flying Enemies”)— but Deed did at least know Méliès, so maybe there’s something to it after all. Deed began his movie career by appearing in the French fantasist’s An Extraordinary Dislocation, and a few of his other acting gigs (like The King with the Elastic Head and The Devil’s Son Spends the Night in Paris) sound very much like the sort of thing Méliès would have made, even if he actually had nothing to do with them. Either way, it’s clear from what remains of The Mechanical Man that Deed was a filmmaker of considerable ingenuity. Admittedly, his best ideas don’t always work in practice. The climactic battle between the robots quickly settles into a rather static tableau of them rocking back and forth in a mutual bear-hug and zapping each other with their electric hands, and the shots of Mado’s machine, undercranked and double-exposed, chasing after the D’Ara family car are delightful for all the wrong reasons. However, when you bear in mind that we’re talking about someone who spent most of his career playing a guy named “Cretinetti” over and over again, the conceptual sophistication of The Mechanical Man starts to look very impressive indeed. This is not to say, of course, that this movie comes as a complete departure from Deed’s past. The mere fact that Modestino D’Ara is more often called by the nickname, “Saltarello” (loosely translated, “That Little Jumping-Around Guy”), should give sufficient indication of what his scenes are like, and if there is an upside to the disappearance of the other two thirds of the film, it is that we are thereby presumably spared the other two thirds of Deed’s performance.

But what really fascinates me about The Mechanical Man is how it seems to fit into the developmental arc of Italian genre cinema as a whole. Scenes like the carnage at the opera house simultaneously point backward to the lavishness of Italy’s earlier historical epics (think Cabiria or the 1913 versions of Spartacus and Quo Vadis?) and forward to the shocking violence of that country’s horror and action films of the 1970’s. Mado, although her most obvious tie is to the anti-heroes of the previous decade’s French serials, like Fantomas and The Vampires, might also be seen as a distant forerunner of the diabolical women who would become a vital element of so many Italian movie formulas in the 60’s— especially once her final-scene unmasking as the seemingly upstanding Countess Donatieff places her within the dualistic tradition most closely associated with Barbara Steele. And speaking of that unmasking, the inexplicable fact that Mado isn’t unmasked upon her initial arrest suggests that logic was no more a concern for Italian filmmakers in the early 20’s than it would be from the mid-1950’s onward. We can and should remain agnostic about most of The Mechanical Man’s apparent plot-holes on the grounds that we’re missing the bulk of the movie, but there’s simply no way that anything contained within the thousand vanished meters could adequately justify Mado being sent to prison without anybody becoming even the slightest bit curious about her identity! Finally, it’s amusing to note that even as early as 1921, the Italians just couldn’t resist the temptation to toss in a little bit of purely gratuitous nudity. So you see what I mean, then. For better and for worse, The Mechanical Man hints at damn near everything we’ve come to expect from Italy in the years since. Is there any other national film industry that can be said to offer such consistency as that?

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact