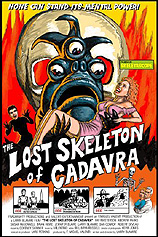

The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra (2001) ***

The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra (2001) ***

There have been a number of affectionate parodies of 1950’s horror and sci-fi movies made over the past quarter-century or so, but for the most part, they’ve been relatively unambitious affairs, often taking the form of short sketches (like the title segment of Amazon Women on the Moon) or snippets of film-within-a-film (as in Popcorn or the Hallmark Channel Halloween movie Monster Makers). Meanwhile, in feature-length films that use a spoofing homage to the 50’s as their main point of departure (think Mars Attacks! or Killer Klowns from Outer Space), the 50’s angle is usually nothing but a point of departure, and we end up with a more or less modernistic take on old-fashioned subject matter. The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra is different. With this film, writer/director/star Larry Blamire has undertaken to reproduce as exactly as possible the complete experience of watching a movie from those bygone days when doo-wop ruled the airwaves, brassieres looked like the business end of a double-barreled torpedo tube, and cars carried enough brightwork to keep all the chromium miners in Albania whistling while they worked for an entire decade.

How committed was Blamire to achieving the perfect 50’s feel? Well, for starters, he shot The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra in black and white, on location in Bronson Canyon, and scored it with musical cues recycled from actual 50’s monster flicks— and of course, the main characters are a deeply tanned, square-jawed scientist and his wife. Dr. Paul Armstrong (Blamire) has come to the world’s most famous stretch of semi-arid countryside in search of a meteor which he believes (for reasons that he never finds time to explain) to be composed of a rare radioactive element called atmospherium. Betty Armstrong (Fay Masterson, who had appeared in Eyes Wide Shut, of all things, just two years previously) is along for the ride mainly because this could hardly have been convincing as a 1950’s monster movie without some heavily coifed young woman to go tottering around through the rocky hills on a pair of wildly impractical high-heeled shoes. The Armstrongs have arranged to rent a cabin to use as their base of operations during the meteor hunt, but they’re not really sure how to get there. Luckily, there’s a farmer (Raiders of the Living Dead’s Robert Deveau) standing beside the road to give them directions: “Stay on this road here past Dead Man’s Curve. You’ll come to an old fence, called the Devil’s Fence. From there, go on foot ‘til you come to a valley known as the Cathedral of Lost Soap. Smack in the middle is what they call Forgetful Milkman’s Quadrangle. Stay right on the Path of Staring Skulls, and you’ll come to a place called Death Clearing. Cabin’s right there— can’t miss it… A lot of folks are superstitious around these parts.” You don’t say…

Meanwhile, another scientist, Dr. Roger Fleming (Brian Howe), is also prowling through the hills in search of something. He’s trying to find Cadavra Cave, the supposed resting place of the legendary Lost Skeleton of Cadavra. Who did the skeleton belong to, how was it lost, and what body of dark rumor has accrued to it in the years since? If anybody knows, they don’t bother bringing it up. Regardless, Fleming is also lucky enough to encounter at random a local who is able to steer him toward his goal, the perpetually smiling park ranger known as Ranger Brad (Dan Conroy). Ever heard anyone describe somebody as a “happy asshole?” Well, Ranger Brad is what they meant by that, and one needn’t be as ostentatiously villainous as Dr. Fleming to want desperately to be out of the man’s company as quickly as possible. Fortunately, Cadavra Cave proves to be very close at hand. What’s more, that “lost skeleton” turns out to be lying in plain sight beneath a blanket in the middle of the cavern floor, not 40 feet from the cave’s entrance— maybe the locals just haven’t been looking for it very hard. Fleming’s aim in seeking the Temporarily Misplaced Skeleton of Cadavra is that he believes the old pile of bones holds a power that will enable him to conquer the world. No, I’m not quite sure how he figures that either. In any case, Fleming’s efforts to reanimate the skeleton succeed only in awakening its “skeleton brain;” it can communicate telepathically, and even control minds at a considerable distance, but it is unable to leave the cave unless someone were to toss it in a sack and carry it out. In order to move about on its own, the skeleton will need an outside power source— like, say, a nice big hunk of atmospherium.

That night, while the Armstrongs putter around their rented cabin and Dr. Fleming struggles with only limited success to bring the skeleton to life, an alien spacecraft sets down not far away. No sooner does this happen than something slays that helpful farmer when he goes to investigate what’s got his cattle so worked up. Shortly after dawn, we meet Kro-Bar (Andrew Parks) and Lattis (Susan McConnell), the pilots of the alien ship, and learn more or less what has brought them to Earth. Evidently, they were on their way back to their home planet of Marva when their vessel (it resembles nothing so much as a coffee can outfitted with a nose cone and strange, scaffolding-like delta-wings) sustained some sort of damage, forcing them to land on the nearest inhabitable world. The ship’s power core is totally burned out, and unless Kro-Bar and Lattis can locate a source of atmospherium to replace it, they might as well just apply for green cards and call it a day. The aliens have a second problem, too, in that their pet mutant seems to have escaped from the ship, endangering the lives of “untold millions” of Earthlings. I’m guessing we know what killed that farmer now, wouldn’t you say? While Kro-Bar makes what repairs he can, Lattis sets out to hunt the mutant with her Transmutatron, a raygun-like device capable of altering the form of any living thing, with which she hopes to turn the mutant into something less menacing.

As the Great God Coincidence would have it, both Lattis and Dr. Fleming find themselves within range to overhear the conversation when the Armstrongs return from their successful meteor hunt, chatting all the while about the potential value of atmospherium to humanity. Thus it is that the aliens and the mad scientist each surreptitiously trail Paul and Betty back to their rented cabin. The Armstrongs, who will have earned several times over some sort of award for oblviousness by the time all is said and done, don’t notice any of their pursuers, but Fleming spots Kro-Bar and Lattis, and correctly identifies them as extraterrestrials. He will not be fooled even after the aliens use their Transumtatron to make themselves “look exactly like the Earth people” (that is to say, to convert their “futuristic” jumpsuits into a typically 50’s suit and dress). While the space travelers introduce themselves to the Armstrongs under the remarkably unpersuasive “Earth names” Bammen and Turgasso (assisted somewhat by Betty’s convenient assumption that they must be the Taylors, from whom she and her husband are renting the cabin), Fleming also uses the Transmutatron to create a false identity for himself. Reasoning incomprehensibly that he will seem less suspicious if he is accompanied by a woman, the scientist turns the alien device on a group of forest animals to create Animala (Jennifer Blaire— apparently the real-life wife of Larry Blamire, the lucky bastard). After giving the feral girl a crash course in both the English language and rudimentary behavioral norms, Fleming leads her to the cabin, knocks on the door, and presents himself and his companion to the Armstrongs as Rudolf and Pammy Yeaber. And no, no one ever thinks to wonder why exactly the “Yeabers” have decided to drop by for a visit.

While all that is going on at the cabin, Ranger Brad has found the dead farmer, and he takes it upon himself to alert everyone in the area that some dangerous animal is apparently on the loose. He too is killed by the mutant immediately after leaving the Taylor cabin (never in the annals of cinema has there been a conversation making more frequent use of variations on the phrase “horrible mutilation”), and not even Kro-Bar’s obvious knowledge of what did the ranger in is enough to raise more than a temporary concern in Paul Armstrong’s mind that his uninvited guests might not be quite who they say they are. Paul and Betty go to bed as oblivious as ever, leaving Fleming to confront the aliens with his awareness of their common goal. Together, they scheme to relieve their hosts of the meteor, and share the atmospherium between themselves. Unfortunately for the aliens, Fleming has no intention of parting with any atmospherium once the meteorite is in his hands (“This isn’t like our sharing at all— it must be Earth-sharing,” Lattis laments when it comes to her attention that she and Kro-Bar have been played), and what’s worse, the skeleton turns out to have designs on Lattis once Fleming has it up and running again. The aliens are forced to collaborate with Paul and Betty instead, and to hope that the crush which the wandering mutant inevitably develops on the scientist’s wife will enable them to use its monstrous strength to overcome the skeleton.

So for those of you who haven’t been keeping score, we have here a strangely unobservant scientist and his dimwit wife. We have a radioactive meteorite containing a rare and powerful material with an extremely silly name. We have shipwrecked aliens attempting to pass as human beings— and shipwrecked aliens obviously modeled on Eros and Tanna from Plan 9 from Outer Space at that. We have an evil scientist inexplicably seeking to conquer the world by exploiting the power of some legendary magical whatsit. We have a rubber-suit monster every bit as overdesigned and shitty as anything created by Paul Blaisdel. We even have a sexy and sinister cat-girl and a couple of scenes that look suspiciously like a non-nudie version of something out of Orgy of the Dead. Not since Humanoids from the Deep have I seen a movie go so far out of its way to include every imaginable cliché that could possibly have been squeezed into it. Add to that the stock music, the black and white cinematography, the exaggeratedly inane dialogue, and the Bronson Canyon locations, and you get something like the Platonic ideal of the dime-budget 50’s horror/sci-fi film. The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra was obviously made by people who absolutely love this kind of crap, and who have spent an awe-inspiring amount of time over the years watching it— no one who didn’t could have captured so many of the nuances so perfectly. Surprisingly, however— and pleasantly so— the funniest material in The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra stems not so much from its pitch-perfect simulation of 50’s drive-in badness as from those scenes in which the old cliches collide in ways never seen in their own day. The best example is the dinner scene, which takes its cues from the old chestnut about the aliens attempting to mimic Terran folkways, and getting them conspicuously not quite right. Blamire multiplies the hilarity of this scene beyond anything else of its kind by having Kro-Bar and Lattis look to Animala, who knows even less about human table manners than they do, for guidance. For most of the movie, Blamire is content to aim for a knowing chuckle, but that particular scene is laugh-out-loud hysterical, and probably doesn’t require a deep familiarity with antique monster movies to get the humor across.

The one serious mistake to be seen in this film lies in its pacing. Unfortunately, the only feature of the old movies Blamire didn’t duplicate was their 70-minute running time, and The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra bogs down badly at about the halfway point. Some 50 minutes in, most of the momentum just dribbles away, and it’s easy to get the impression that Blamire honestly didn’t know what to do next. In a sense, that sort of plot implosion just adds to the period feel, as it is perhaps the most commonly encountered defect in cheap horror and sci-fi films of the 1950’s that cannot be traced directly to a lack of funding, but modern notions of feature-length running time mean that The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra has an extra fifteen or twenty minutes in which to spin its wheels before the deliberately tacked-on-feeling conclusion, and that’s fifteen or twenty minutes too many.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact