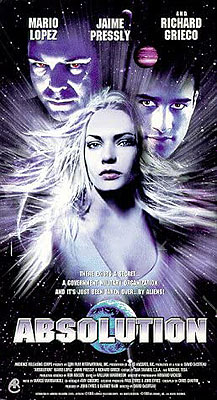

The Journey: Absolution (1997) -½

The Journey: Absolution (1997) -½

The first time I saw The Journey: Absolution, I was so utterly bewildered by its mere existence that I was basically unable to process much of anything else about it. Writing about the film immediately afterward, I drove myself to achieve far and away my fastest turnaround time ever, because it seemed absolutely imperative that I get the review down on paper while that sense of “What in all nine of the Hells did I just watch?” was still a live thing thrashing around in my brain. It should go without saying that the resulting piece was hardly my best work, but even if I’d taken my time with it, I don’t think I’d have managed much better. That’s because in February of 2001, I was missing the all-important central piece of The Journey: Absolution’s puzzle: I had never heard of David DeCoteau.

It would be a damned dirty lie to claim that anything about The Journey: Absolution makes sense in the way that we normally use that term, but when you realize that DeCoteau isn’t just some rando director of straight-to-video schlock, it becomes possible at least to understand how such things as this movie can be in the first place. David DeCoteau, you see, is a gay ex-pornographer who spent the late 80’s through roughly 2010 cranking out sexploitationy horror, sci-fi, and suspense movies for the mainstream home video market. These pictures were all aimed at an audience of straight males who could reasonably be presumed for most of those years to be at least mildly homophobic, yet DeCoteau nevertheless always made sure they would cater to his own personal tastes in one way or another. DeCoteau may be a lousy director, but he became very good indeed at making it look like an accident that his movies so consistently featured large numbers of extremely pretty boys finding one excuse after another to hang out together in their underwear. And because he came up from the porn industry, he knew how to economize ruthlessly enough to make something halfway professional-looking even on a 21st-century Charles Band budget. The Journey: Absolution wasn’t a Band production, but it’s about on the same level as most of the work DeCoteau was doing at the time for Full Moon, Torchlight, and the other Band video labels during the late 90’s. Although practically worthless from an entertainment perspective, it’s arguably the ideal introduction to its director’s work, since it improbably manages to be Starship Troopers: Twink Academy and No Homo, Bro: The Motion Picture at the same time.

The Journey: Absolution begins on an ambitious note, which it conspicuously fails to hit. One of the crappiest CGI asteroids I’ve ever seen smacks into the Earth, rendering much of it uninhabitable with a montage of stock disaster footage, after which an onscreen caption informs us that it’s “30 years later.” But just because that makes this technically a post-apocalypse movie, don’t go expecting DeCoteau or screenwriter Chris Chaffin— who never worked again in that capacity— to make any kind of investment in establishing what life After the End is like for the populace as a whole. No, we’ll be spending all our time at a military school called Fullerman Academy, where this doomed world’s buff, shapely, and rigorously chest-waxed young men are sent to run obstacle courses, take showers, lounge around in skin-tight boxer shorts, and impugn each other’s heterosexuality in order to provoke impromptu seminude wrestling matches. The ill-fitting newcomer through whose eyes we inevitably see Fullerman is Ryan Murphy (Mario Lopez, from Depraved and Fever Lake, whom normal people at the time would have known mainly for all those years he spent in the cast of “Saved by the Bell”), but even he won’t help us much when it comes to figuring out why this institution exists, or how it fits into any kind of bigger picture. That’s because his reasons for enrolling are idiosyncratic to the point of uniqueness: Murphy is here to uncover what happened to a friend of his by the name of Liles (Daybreak’s Charles Mattocks), who disappeared without a trace not long after he matriculated. It will later become apparent that Murphy and Liles alike were sent by some manner of authority structure to investigate deeper irregularities at Fullerman, but for now it just looks like Ryan is doing the Shock Corridor thing on his own initiative.

Murphy is assigned to Echo Barrack, where he quickly befriends Dallas (Justin Walker, from Boltneck and the “Roger Corman Presents” remake of Humanoids from the Deep) and Quintana (Nick Spano, of Time Chasers), and makes enemies of Hubbard (Greg Serano, from Terminator: Salvation and The Postman) and Dragotta (Damon Sharpe). Outside the barracks, he makes an enemy of an older man named Bateman (Steve Wilder, who went on to Hallucinogen and Dark Honeymoon), who could equally well be one of the academy instructors or just something like the senior class president. That’s obviously bad news, but it isn’t half as bad as the rapidity with which Murphy draws the ire of school commandant Sergeant Bradley (Richard Grieco, of Circuit Breaker and Tomcat: Dangerous Desires, whom normal people at the time would have just barely remembered as that schmuck the Fox network hired to replace Johnny Depp on “21 Jump Street”). Of course, it’s immediately apparent that Bradley is batshit insane, so I guess there’s a sense in which being welcomed by him at first sight would be worse news still. On the upside, Murphy establishes an almost instant rapport with Allison (Jaime Pressly, from Piñata: Survival Island and Poison Ivy: The New Seduction), one of two girls from the nearest settlement who regularly sneak into Fullerman’s supposedly secure underground campus in a desperate attempt to convince us that all these perpetually grappling twinks are totally straight, yo.

You get no points for figuring out that Bradley is behind whatever malfeasance Liles came to Fullerman to expose, but anyone who sees the sergeant’s true agenda coming is either a prophet or a lunatic— possibly both. When Murphy finally becomes a big enough pain in Bradley’s ass to get himself locked in the brig, he finds that his cellmate is none other than Liles. Liles explains that the “Z Team” which all the go-gettingest Fullerman cadets aspire to join is really some kind of mind-control cult held together with performance-enhancing and personality-suppressing drugs, and that Bradley’s been conditioning them to become his own private army for use on something he calls the Day of Reclamation. Neither Liles nor Murphy understands what that means, though, until Allison helps them escape, and they all go search the commandant’s office. There, they discover some kind of holographic briefing from Bradley’s true masters. Turns out he’s a disguised member of the extraterrestrial race which sent that asteroid 30 years back, and that everything that’s happened since then has been part of a long-range plan for the colonization of Earth to replace the aliens’ own dying world. The nuclear winter-like conditions created by the space rock remade the planet’s climate to suit the invaders’ physiology, and depleted the human population to a more manageable size for conquest, while the Z Team and Fullerman Academy itself exist to protect the stargate device in the basement through which the aliens will come when their planet falls into the correct alignment with Earth. That’s going to happen much sooner than anyone but Bradley would like, and before we know what hit us, it’s twink against twink with the fate of two worlds in the balance.

There are two things about The Journey: Absolution that any slightly attentive viewer will notice rather quickly, and then become increasingly awed and perplexed by as the movie wears on. The most conspicuous, of course, is the inextricable tangle of homophobia and homoeroticism created by the interaction of Chris Chaffin’s script and David DeCoteau’s direction. In what is probably a more or less accurate reflection of the institutional culture of places like Fullerman Academy in the real world, staff and higher-ranking cadets are constantly casting aspersions on the underclassmen’s masculinity, but Chaffin has the performative fag-baiting turned up to eleven just all the time. Meanwhile, DeCoteau has stocked the film with actors who look like models from the old “physique” magazines of the 1950’s, and dressed them all more often than not in nothing but nut-hugging white boxer shorts and combat boots. Even when the Z Team enrollees partake of their late-night pistol-pointing and chalice-swigging rituals, they do it in their jackboots and underpants. The numerous locker room scenes are almost perfect gender-flipped counterparts to the ones in girls’ gyms familiar from a thousand teen sex comedies of the 70’s and 80’s. And then there’s the frankly astounding scene where the Z Team bring Bradley all of Murphy’s personal effects after locking Ryan in the brig (“Go in his barracks and check every inch of every shit he has!” Bradley orders), which culminates in the commandant holding each item up to his face in turn and inhaling deeply. (Is the last thing to be sniffed a pair of Murphy’s boxers, by any chance? You better fucking believe it is!) Later on, after it’s revealed that Bradley is an alien, I suppose we can retroactively attribute his behavior to his species having somewhat different sensory apparatus than us, but in the moment? Holy fucking shit…

The other glaring abnormality of The Journey: Absolution is the fact that the movie is more than two thirds over before any indication surfaces that there might be some kind of plot driving it. Seriously, on my first go-round, I had absolutely no idea what this turkey could have been about until well past the 60-minute mark. Despite the occasional line of whispery voiceover in which Murphy mentions Liles— whom at that point we know only from a photo of the two lads together (incredibly, both of them fully clothed!) which Ryan sometimes glances at mournfully— the first two acts have nothing meaningful to tell us about why any of this shit is happening. It’s just a meandering, hour-long beefcake parade.

By no means do the foregoing observations exhaust the catalogue of this movie’s crappiness, either. The boys are all nothing but ambulatory delivery systems for waxed pecs and straining crotch-bulges. Richard Grieco is memorably awful even for him, delivering a performance somewhere between John Travolta at his very worst and a poor man’s Michael Ironside. It’s impossible to tell where a flubbed line was allowed to stand for economy’s sake, and where the dialogue was just that bad to begin with. The sets are cheap and junky, the world-building is nonexistent, and the special effects are Sega Genesis-quality CGI. DeCoteau at least seems to be trying during the fight scenes in the final act, but action is quite simply not his forte. Even worse is the sex scene between Mario Lopez and Jamie Pressly, which seems to go on forever to no good purpose. Heaven knows there’s no trace of actual eroticism in it— although maybe that’s to be expected when a gay guy attempts to depict straight sex. And last but by no means least, let us note that The Journey: Absolution contains neither a journey nor an absolution! A lot of what felt off about this movie fell into place for me once I became better acquainted with David DeCoteau and his work, but the title still fucking mystifies me.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact