J’Accuse!/I Accuse (1919/1921) ***

J’Accuse!/I Accuse (1919/1921) ***

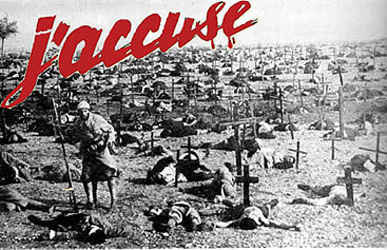

The 58,000 filled body bags that were shipped home from Vietnam between 1961 and 1975 had a tremendous impact on nearly every aspect of American public life, to the extent that the war was still a major cultural and political touchstone fifteen years after it ended. For example, I vividly remember hearing TV and radio blowhards commenting, after the almost absurdly quick and painless US victory in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, that this would finally exorcise the specter of Vietnam from the American consciousness. So consider this, then: in September of 1914, the French suffered nearly half again that many deaths in a single week’s fighting along the River Marne. Estimates of the total French combat losses during the First World War reach up to nearly 1.2 million, to say nothing of the 300,000 or so civilians who accompanied the soldiers into the grave— and this out of a national population slightly less than 40 million, meaning roughly one out of every 27 people killed. Then there were the wounded, another 4.5 million of them, many of whom were permanently crippled, maimed, or disfigured. It is fair to say, then, that World War I left no one in France untouched by its prodigious wastage of human life. The French were hardly alone in that, of course (2.5 million dead out of 65 million Germans, 3.3 million out of 159 million Russians, 725,000 out of 4.5 million Serbs, etc.), but they seemed to catch on just a little bit faster than the other nations on the winning side. In fact, writer/director Abel Gance was hard at work on what might well be the first really significant anti-war movie while there was still a bit of fighting going on, and the final cut of J’Accuse! even incorporated a few clips of genuine frontline footage, garnered with the cooperation of an army hierarchy which Gance had somehow hoodwinked into believing he was assembling a patriotic epic. Only after the film was mostly in the can did anybody think to ask Gance exactly who was accusing whom of what.

Part of what sets the First World War apart from the other major conflicts of the industrial era is the vast discrepancy between popular expectations going in and the actual course of events, even within the first few months of fighting; what nearly everyone believed would be a short and glorious struggle (with the exact definition of glory naturally varying according to which country one happened to be in) instead turned into four meat-grinding years of horror and privation, ending with the political structure that had served Europe ever since Waterloo in ruins. That being so, Gance begins J’Accuse! in peacetime, in the small, Provençal village of Ordevale, seeking to emphasize the breadth of the gulf between the summer of 1914 and that of 1918. In Ordevale, we are introduced to Jean Diaz (The Manor House of Fear’s Romauld Joubé), an idealistic and somewhat impractical poet; Jean’s doting old mother (credited only as “Mancini”); Edith Laurin (Maryse Dauvray), an ex-girlfriend of Jean’s whom he still openly loves; Edith’s mean-tempered, hard-drinking, frequently violent husband, François (Severin-Mars); and also her aged father, Maria Lazare (Maxime Desjardins, from The Mystery of the Yellow Room). Diaz spends his days composing a series of verses he calls Les Pacifiques, and furtively flirting with his ex. François gets wasted, goes hunting, and beats his wife. Edith returns Jean’s attentions with equal furtiveness, obviously well aware of what a horrible mistake she made at the altar. And as for Lazare, he was a cavalry officer (maybe as high as colonel, judging by the epaulets on his old uniform) and a veteran of the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and like so many Frenchmen of his generation, he has spent the ensuing 45 years simmering over the German conquest of the frontier provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. He is thus absolutely thrilled one day in August, when word comes out that war has once again been declared between France and Germany.

Of the other characters, François is the most in tune with his father-in-law. He is mobilized immediately, and he sets out to become a hero of whom the old man can be proud. Indeed, François is much less worried about going to war per se than he is about what might happen between Jean and Edith back home during the 40 days that are scheduled to elapse before the other man’s call-up. And for what it’s worth, Laurin’s worries are well founded. Jean has been waiting years for just such an opportunity, Edith is far from faithful, and when François is rotated back on leave a few weeks later, he is so incensed at what he catches the two lovebirds doing that he packs Edith off to his parents’ place up north. That, as it happens, is a terrible plan. The old homestead is right in the path of the German advance, and Edith is abducted by soldiers and sent across the border in captivity. So great is the affront that even Diaz is moved to vengeance— despite having nearly two weeks to go before mustering out, he reports at once to the academy, and signs up for officer training. As you might imagine, that makes Lazare proud of him now, too.

Edith’s abduction does not stop the soap-opera, though— no, far from it. Up at the front, François gets it into his head that his wife was never really captured at all, and that it’s all been a ruse to cover an elopement between her and Jean. He starts sending irate letters home, and things become increasingly strained between Lazare and Old Lady Diaz. But then Jean shows up in the trenches as (surprise, surprise) Laurin’s new lieutenant, and the cantankerous cuckold is forced to recognize that he was wrong about at least that much. Diaz, for his part, is forced to recognize that François honestly does love Edith, too, when he goes to Laurin’s dugout in the trench system, and sees his incredibly sappy shrine to his wife; guys like François don’t build something like that unless they really mean it, even if they are French. In a roundabout way, that discovery also leads Diaz to win his rival’s respect, for it determines Jean’s response when his commanding officer orders a hazardous reconnaissance mission to investigate reports that the Germans have constructed a massive new ammunition depot in the section of trenches opposite Diaz’s platoon. The major (or whatever he is) wants Laurin on the job, because it’s the next best thing to a suicide mission, and Laurin is universally regarded as the bravest man in the battalion. Diaz, however, sees the recon mission as the perfect opportunity to get himself killed and thereby remove himself from the troublesome three-sided romantic equation. He defies orders by going in himself, intending not merely to report on the enemy ammo dump, but to blow the thing up and go out in a blaze of glory. Jean is a little too successful for his own aims, however, for not only does he Sergeant York the shit out of the German trench, he lives to tell the tale. He also lives to make peace with François, and eventually even to bond with him over their mutual love for Edith, whom they both unspokenly believe they’ll never see again.

The strain of war is constant and grinding, however— even for heroes— and by 1918, Diaz finds himself treading perilously close to complete nervous collapse. Nevertheless, he refuses to go on leave like the regimental doctor recommends, and soon Laurin is writing to Lazare back home, seeking advice on how to persuade Jean to take care of himself before it’s too late. Lazare, as it happens, has some news that ought to do the trick quite nicely— Jean’s mother is very sick, and is probably dying. The next thing we know, Diaz is back in Ordevale with a medical discharge, looking after his ailing mom. His timing is good, too, not just because the old lady doesn’t last very long after his return, but also because Edith has somehow managed to escape from behind the German lines, and is on her way home even now. There’s been a slight complication, however. You know those German soldiers who abducted her four years ago? Well, they raped her while they were at it, and now she’s got a little half-Kraut bastard daughter on her hands. Won’t François be thrilled? Hell, won’t Dad be thrilled? The plan Edith and Jean arrive at is to pass off the little girl as his distant cousin, sent to live with him until such time as things back home settle down from the war. It works out alright until about halfway through François’s next stint on leave, when his mounting suspicions eventually lead him to trap Edith into admitting that the child is hers. At first, François jumps to the conclusion that the girl is the product of an affair between Edith and Jean, but he eventually allows himself to be persuaded of the true story. Not that he likes that any better, you understand. It’s the luckiest thing in the world for Edith’s daughter when François has to go back to the front, and old Maria Lazare doesn’t take the news any better. In fact, he literally runs away from home when he finds out! For that matter, Diaz ends up leaving Edith to her own devices, too; Laurin confides in him his fears that his and Edith’s obvious love for each other will blossom into another affair the moment François is back at the front, and in his war-forged loyalty to his former rival, Jean agrees to re-up and accompany François to the battlefield once more. This time, things go poorly for all concerned. Laurin is killed in action during a major offensive, Diaz’s shell-shock returns with a vengeance, so that he comes home thoroughly unhinged this time, and all of you reading this really start to wonder why El Santo has bothered to review this movie at all.

It’s a fair question. War movies, whatever their political stance, are far outside my usual purview, and as for war movies that would rather be soap operas instead— oh, hang on… I guess I did review Starship Troopers, didn’t I? That was different, though. That had huge, computer-animated bugs blowing up interstellar troopships by crapping jets of blue-hot plasma at them from the surface of an alien planet. What the hell does J’Accuse! have that would make it a fitting review subject for 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting? Well, how about zombies? No, seriously. This movie suddenly turns very strange when Diaz makes his second return to Ordevale, easily strange enough to earn itself a place in these pages. The way he tells it, his last mission before going completely bugshit and deserting his post was to stand night watch over the makeshift cemetery where the casualties of Laurin’s last battle were buried. In the small hours of the morning, all those graves opened up, and the dead men within— in fact, all the war dead everywhere, or so Diaz was given to understand— mustered out for one last, great march. They weren’t bound for the front this time, though. No, this time, the dead were marching home, to see for themselves whether their friends and families and neighbors understood and appreciated their sacrifice, or whether their deaths were as meaningless as they appeared from the vantage point of a shell-hole in No Man’s Land. Diaz announces all this to the assembled people of Ordevale, confessing as he does so that he ran away from his post— ran away from the massed, on-marching ranks of the surly dead— and it initially seems like the whole speech (and the eerie flashback that accompanies it) is nothing more than Abel Gance’s ultimate rhetorical device, the peaceful poet driven mad by war driving home the truth of its destructive folly via metaphorical hallucinations. That’s when the army of maimed and bloodied zombies stagger-march into Ordevale, and begin glaring mute accusations at all and sundry…

It really is difficult to overstate how shocking the transformation is. For some two and a half hours, J’Accuse! has been an effectively mounted but diffuse and distractible meditation on the impact of war upon a thoroughly ordinary love triangle. Then— BOOM!— every man killed in four years of fighting gets up out of his grave and goes home to defy his loved ones to tell him it was worth it. It isn’t handled like the mild intrusions of sentimental fantasy that “The Twilight Zone” would later traffic in, either. These guys look as dead as could be managed with 1919 makeup technology, and they’re not double-exposure ghosts but fully corporeal walking corpses. And what’s more, Diaz hints darkly that they will not be going away if they are not satisfied with the answers they receive from the living. To the best of my knowledge, that jarring shift from mundane melodrama to stark, unflinchingly fantastic horror had as little precedent in the cinema of the day as the industrialized murder machine of the trenches had had in warfare. So while it is indeed Gance’s ultimate rhetorical flourish, it isn’t at all the one the viewer expects, and it is all the more potent because of that. Meanwhile, the climactic genre jump serves the smaller but still laudable purpose of finally giving Gance a subject for his camera that is truly worthy of his great visual imagination. J’Accuse! has been from the beginning an extremely attractive film, and throughout, Gance has found ways to dress up fairly pedestrian subject matter so as to make it more interesting to watch than it has any right to be. For example, during the thematically necessary but inexcusably overlong prewar prologue, there is a scene in which Diaz reads to his mother a poem called “Ode to the Sun.” Instead of tossing up the text of this poem as an intertitle or series thereof, Gance launches off on a montage of pastoral imagery meant to evoke the same emotional response in the audience as Jean’s recitation wins from his mother. Gance is using the strengths of one medium to stand in for those of another, and it works. (Although it occurs to me that it probably wouldn’t have in a talkie, or at least not with the purity that it has here.) The trouble is that Gance needs to play tricks like that, because so much of J’Accuse! can be made interesting only in spite of what’s happening in the story— except for a few key moments of honest drama, the script is like a big, heavy barge that the imagery must tow. Fortunately, however, the rising of the war-dead changes that dynamic. It will come too late for many viewers, I think, but once the dead are walking, the narrative finally starts moving sustainedly under its own power, and Gance’s capable direction becomes merely the tugboat nudging it through the more delicate maneuvers on the way to the docks from the harbor entrance.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable focusing on the olden days, when you had to bring along your reading glasses when you went to the movies, but never had to contend with the booming of the explosion flick in the auditorium nextdoor intruding upon your enjoyment of the sensitive relationship drama you were trying to watch. Click the link below to peruse the Cabal's collected offerings, and don’t mind the smell— that’s just the nitrate in the film stock rotting away to vinegar vapor before our noses...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact