Invasion from Inner Earth / Invasion from the Inner Earth / Hell Fire / They (1974) -***½

Invasion from Inner Earth / Invasion from the Inner Earth / Hell Fire / They (1974) -***½

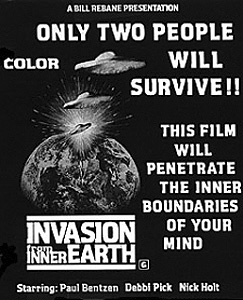

The modern micro-budget movie scene could never have existed without the invention of videotape. Film simply has too much inherent cost overhead, particularly in the form of lab fees for developing the thousands of feet of celluloid required by a feature-length movie. Nevertheless, the micro-budgeteers do have obvious antecedents in what might be called the regional filmmakers of the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s. From 1948, when the court-ordered demise of vertical integration in the movie industry created unprecedented opportunities for independent filmmakers, until the early 1980’s, when runaway inflation eliminated those opportunities by squeezing the independents’ profit margins to the vanishing point, it was relatively easy for sufficiently driven producer/directors working totally outside the Hollywood system to crank out droves of low-budget exploitation movies and get them profitable theater bookings within a relatively narrow geographic range. The best-known example of the phenomenon is probably the New York grindhouse market centered on the Times Square section of 42nd Street, but there were underground distribution networks all over the country capable of creating local luminaries who might make a career for themselves in the movies even if they attracted little or no notice outside their home state— though there were of course a few regional filmmakers whose natural gifts for self-promotion ensured that they would not remain strictly regional for long. So while 42nd Street had Andy Milligan and the Findlays, Chicago had David Friedman and Herschell Gordon Lewis. Baltimore had John Waters. The Deep South had an entire industry all its own. And Wisconsin had Bill Rebane. The year before he awed the world (or at least the Great Lakes region) with The Giant Spider Invasion, and nine years after his abortive first effort, Terror at Halfday, was sold to Herschell Gordon Lewis for completion as Monster a Go-Go, Rebane brought forth a film that he would never be able to live down if anyone had actually seen it. One of the most freakishly hapless non-movies of its era, Invasion from Inner Earth marked Rebane’s first attempt to milk the UFO mania that was then gathering strength again after a decade’s hiatus. You won’t believe your eyes.

Pay very close attention to the pre-credits sequence; it offers the only hints you’ll get as to what this movie might be about until well past the hour mark. A man who rather resembles the unholy love-child of John Saxon and George Zucco walks into some kind of conference room, and haltingly tells the assembled important-looking people that there are still scattered reports of remote areas not yet touched by “this dreadful disease.” Panicked crowds flee down the streets of Tomahawk, Wisconsin, past a scattering of fallen bodies and vast plumes of red smoke billowing up from the sewers and storm drains. A shimmering, blue-white light is superimposed over an image of the rotating Earth. A flying saucer so pitiful that even Ed Wood would have hung his head in shame over it is seen in poor focus amid a welter of flashing red and green lights. And a barely disguised uncredited rearrangement of Ennio Morricone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly theme plays audaciously over the opening credits.

Meanwhile, in the middle of fucking nowhere, forest guide and bush-plane pilot Jake Stephens (Nick Holt) is returning home from a notably unsuccessful hunting expedition. As he perplexedly explains to his sister, Sarah (Debbi Pick), he didn’t see a single deer all day, and even birds and squirrels were unaccountably scarce. It then comes out in conversation that the Stephens siblings are playing host to a trio of researchers from… well, somewhere… who are researching… well, something… in their neck of the woods, and who are preparing to return whence they came after a three-week stay at the cabin. Jake thinks maybe Sarah ought to come along and spend a few days in town, especially in light of the evident attraction that has developed (or so we are told— we’ll certainly never see it) between her and Eric (Karl Wallace), the putative leader of the researchers. Sarah denies that there’s anything between her and Eric and asserts that she hates towns. Thus it is that she remains at home when Eric, Stan (Paul Bentzen, from The Devonsville Terror and The Alpha Incident), and Andy (Robert Arkens) climb into Jake’s plane for the flight into Hightower and thence to civilization. (Stan, I hasten to emphasize, will not be identified by name for over 38 minutes.)

It is on the approach to Hightower’s puddle-jumper airport that our heroes first encounter the effects of whatever that shit before the credits was about. The airport employs exactly one air-traffic controller, a man named Sam (Arnold Didrickson), and Jake has the damnedest hard time getting him on the radio. When he goes in low to have a look around, Jake spies Sam standing in the middle of the runway, waving his plane away. Over the radio a short while later, Sam cautions Jake not to land at Hightower— there’s a plague-like disease gripping the town, and everyone is dying off. Hell, Sam’s sick himself, and doesn’t anticipate lasting much longer. Jake tries to land anyway, but Sam stops him by rushing outside and standing in the middle of the runway once more. Utterly flummoxed, Jake breaks off and sets a course for Bear Creek Lodge instead. The lodge has its own airfield, and the owners generally keep the place stocked with fuel even when it’s closed for the winter, as it is now. There’s also a shortwave radio rig at the lodge, with which Jake ought to be able to contact somebody to confirm or refute Sam’s curious story. When Jake and the researchers land, however, they find all the avgas tanks empty, and even after Stan and Andy get the generator started so as to power the radio, Jake and Eric can raise nothing but static. That isn’t the weirdest thing that happens at the lodge, either. Jake and Eric go off to reconnoiter as evening approaches, leaving Stan and Andy behind to keep trying the radio. The latter men begin hearing strange sounds— but not over the radio— and then a mysterious red light with no apparent source begins shining on the wall of the room behind them. Both the light and the noises cease after perhaps a minute, but the unexplained event leaves both men feeling uneasy. They’re happy to get away from the lodge once the others return, even if they’re just going back to the Stephens cabin.

We have now reached the point in the film where things sort of stop happening. I know, I know— they haven’t even really started happening yet, but there’s nothing I can do about that. For the most part, the rest of the movie consists of Jake, Sarah, Stan, Eric, and Andy cooped up in the cabin, getting on each other’s nerves and worrying about… um, I’m not really sure what, actually. They listen to a bunch of static on the radio, Andy complains constantly, and Stan talks a lot about UFOs for some reason— I guess because of that business with the red light at the lodge. The Stephenses and their guests also receive periodic radio messages delivered in a droning monotone, asking cryptic questions about their circumstances in the cabin. Then every once in a while, we’ll get a short interlude regarding the outside world. For example, a boy and a girl vanish into thin air while watching a late-night TV talk show on which a remarkably unctuous host interviews two guests about their respective UFO sightings. Eventually, Andy gets all cabin-fevered out, steals Jake’s plane, and flies off in it. He doesn’t get far before the red light shines on the control panel, causing the plane to explode in midair. Then Jake tries to reach town on his snowmobile, but vanishes just like the TV kids after a beautifully pointless trekking sequence. (Listen closely to the soundtrack during the third segment of the trek. Just trust me.) We get to see a bit more of the chaos in Tomahawk, and marvel at Bill Rebane’s piss-poor conception of a big action set-piece. Finally, the remaining threesome strap on rucksacks for a desperate bid to hike to the nearest settlement. Along the way, Stan regales his companions with his theory about what’s really going on. Naturally, it involves flying saucers, but not flying saucers from outer space. No, Stan believes the aliens have come from inside the Earth. Here— he can tell the story better than I would:

| Stan: | About 8000 years ago, the planet Mars came within very close proximity to the Earth— even closer than our own moon. |

| Eric: | You mean like the comet Kahutec, just passing us by. |

| Stan: | No, no— nothing like that. You see, in this case, Mars stayed close to the Earth for approximately 2000 years. Now it’s just a fact of science that, because of the electromagnetic fields, you just can’t have two immense heavenly bodies in such close proximity like that for any length of time. And so what happened, all hell just broke loose. Now, the inhabitants of Mars, they knew the end was near, so they knew that the only thing they could do was to get out, to make a split. So the obvious place to go was Planet Earth. |

| Sarah: | But weren’t things just as bad here on Earth? |

| Stan: | Yeah, they were. That’s a good question. During that time… well, how does the Bible describe it? The Period of the Seventh Seal. It was during this time the great flood, earthquakes, fire— but you see, this was all irrelevant because the Martians were not interested in the surface of the Earth, because through their advanced technology, they had made scouting probes, and they discovered that the interior of the Earth closely approximated their own atmosphere and was very compatible to them. So in the words of the old master, Jules Verne, a journey to the center of the Earth seemed about the only way out. |

I tell you, that man is a fucking genius. Puzzlingly, Sarah, Stan, and Eric all split up at this point. There’s no reason given for doing so, and everybody spends most of what little remains of the running time trying to reunite, so I have no idea in hell what this could possibly be about. Eric freezes to death while blundering around in the woods, but Sarah and Stan eventually find each other. What happens next is so utterly inexplicable that I’m not even going to talk about it— you need to see it completely cold, the way I did, in order to appreciate it fully. I will, however, say that at no point in the film do our heroes ever come into direct contact with the aliens, nor is there any sort of resolution at all. Invasion from Inner Earth ends with 90-odd minutes’ worth of loose ends snaking out in all directions from a single, monumental “What the fuck?!?!”

Most movies which earn high negative ratings from me are loud and obvious about their badness, but the perverse charms of Invasion from Inner Earth are more subtle. The only special effects in the strict sense are a pair of briefly glimpsed flying saucers. There are no riotously silly rubber-suit aliens, but merely a red glow and some plumes of colored smoke. The movie is almost literally all talk, which is something I normally despise. What makes Invasion from Inner Earth so wonderful is its complete— and apparently inadvertent— disregard for even the most rudimentary narrative technique. Evidently the world is being conquered by incorporeal aliens, and if you want to take Stan’s word for it, those aliens are Martians who have been living in the Earth’s interior for a good six or eight thousand years. But we get no sense of the aliens’ agenda, no indication of why they’ve suddenly decided to move upstairs after several millennia of living contentedly below the surface, no clue as to how their purposes are served by a disease that wipes out any form of animal life that encounters it. For that matter, we can’t even be certain that the aliens and the disease have anything to do with each other! The focus of the film is on a group of characters so far out of touch with the rest of the world that they remain entirely in ignorance of the invasion’s course from beginning to end. There is no semblance of rising action, no climax whatsoever, and only the most perfunctory gestures in the direction of interpersonal drama. And yet to all appearances, neither Bill Rebane nor anyone else involved in this movie’s creation had the slightest idea that they were doing anything out of the ordinary. Rebane treats Stan’s campfire tale about Martians in the Earth’s mantle as if it not only made sense, but actually made sense of the movie. He treats stuff like the talk show interlude as if it really did tell us something about conditions in the outside world. He treats a final scene that bears no visible connection to anything that came before it as if it were the only logical way to end the film. In short, Rebane fails with unprecedented totality in his task as a storyteller. The audience leaves Invasion from Inner Earth in utter bafflement, having not the foggiest notion of what they just saw.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact