The Inferno / Dante’s Inferno / L’Inferno (1911) **½

The Inferno / Dante’s Inferno / L’Inferno (1911) **½

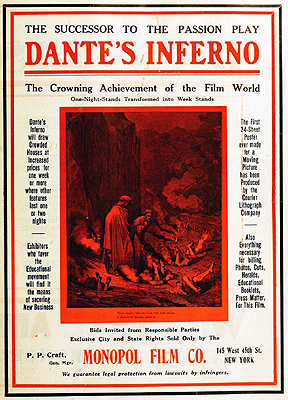

In my review of Cabiria, I talked a bit about the role of Italian filmmakers in the invention of what we now think of as the feature motion picture. Well, now we’re going to look at what might actually have been the moment of that invention. As always when discussing the early silent era, some amount of qualification and bet-hedging is in order, but to the best of my knowledge, The Inferno, directed by Francesco Bertolini, Adolfo Padovan, and Giuseppe de Liguro, is the world’s oldest surviving feature-length movie, and has a plausible claim to be the first ever made. Although it’s quite short by modern standards (the edition I watched clocks in at about 68 minutes), it represented a tremendous advance in ambition and scope at a time when the rest of the industry was thinking in terms of what would fit onto a single camera reel, and when most cinematic adaptations of literary sources consequently limited themselves to presenting individual scenes or at most a compilation of selected highlights. Bertolini, Padovan, and de Liguro stopped short of filming the entire Divine Comedy, it’s true, but even a good-faith effort to present the first book in its entirety was an exceedingly tall order in their day.

Once that trio had it in their heads to attempt a project on such an unprecedented scale, it was natural for several reasons for them to look toward The Divine Comedy as their source material. For one thing, the subject matter lent itself to the strengths of the new medium, as demonstrated by the works of pioneers like Georges Méliès, Walter R. Booth, and Segundo de Chomon. For another, The Divine Comedy’s episodic structure meant that a film version could function as a long succession of five-minute vignettes of the kind that everyone in the business already knew how to make. And of course it didn’t hurt that The Divine Comedy, The Inferno especially, was what we would today call a pre-sold property. That is, it had an established reputation in its original medium, and presumably a ready-made audience to go with it. Which brings us to Dante Alighieri, the man who wrote The Divine Comedy, and to the most compelling reason for Bertolini and company to try adapting The Inferno. For Italians, Dante holds a cultural position comparable to that of William Shakespeare among English-speakers, and although he has plenty of other subsidiary claims to fame, La Comedia Divina is the principal basis for his stature. That’s because it was the first work of its kind to be composed in vernacular Italian, implicitly asserting for that language equality with Latin and Greek as a worthy medium for epic poetry, then considered the highest expression of the wordsmith’s art. Already by Michelangelo’s time, Dante was a hero wherever an Italian dialect was spoken, and by the 19th century, Italian nationalists had adopted him as their spiritual progenitor. Because Italian filmmaking in the 1910’s was heavily entangled with Italian nationalism, it only makes sense that Alighieri would get roped into the former on the strength of his importance to the latter.

Okay, so what is The Divine Comedy? Well, it hasn’t really got a plot. It’s more an allegorical fantasy travelogue in which Dante Alighieri himself is taken on a tour of the Roman Catholic afterlife, guided first by the ancient Roman poet Publius Virgilius Maro, and later by Beatrice Portinari, the daughter of Florentine banker Folco Portinari. The author selected those two figures carefully. Virgil was a personal idol of his— not just the greatest poet of ancient Rome, but also the writer whose epic, the Aeneid, did for Latin what Alighieri was trying to do for Italian with his own. But Virgil was viable as a tour guide only for Hell and Purgatory, because admitting a pagan into Heaven, even temporarily, was an obvious theological impossibility. For Paradise, then, Dante turned to the Portinari girl, climbing one more time onto a hobby horse that he’d been riding since the day he first put pen to paper. Beatrice, you see, was basically the whole reason why he got into the writing trade in the first place. They were introduced to each other as children of about nine years, and apparently met only once more in their entire lives, as teenagers. Nevertheless, Dante fell obsessively in love, and he remained obsessively in love with Beatrice until the day he died, even despite both his and her arranged marriages to other people. His earliest poems were troubadour laments bemoaning his heartbreak at being kept forever apart from the object of his affections; Beatrice, from what little is recorded of her from points of view other than Dante’s, found these outpourings equal parts creepy and absurd. Later, as his writing matured, Alighieri turned instead to praising her virtues, doing so even more immoderately than he had formerly proclaimed his own sorrow. Inevitably, the praise grew more strident still after 1290, when Beatrice died— history doesn’t record how— at the age of just 24 years. So who better to conduct the fictional Dante around Heaven than the dead girl whom the real one had built up in his mind and heart to be the next best thing to a saint?

Anyway, getting back at last to the movie, we begin with Dante (Salvatore Papa) lost in the forest of spiritual error, seeking, as ever, reunion with his lost love. His progress toward the mountain which gives access to Heaven is blocked by a leopard, a lion, and a wolf, each embodying a sin to which Alighieri reckons himself especially susceptible. (The depiction of these beasts is charmingly goofy, by the way. The big cats are extras in pantomime suits, while the wolf is an excitable German shepherd.) Luckily for Dante, Beatrice (Emilise Beretta) takes notice of his plight, and intervenes on his behalf. Traveling to the Limbo of Virtuous Pagans in the First Circle of Hell (the Club Fed of the Underworld), she enlists Virgil (St. George and the Dragon’s Arturo Pirovano) to guide Dante to the threshold of Paradise. True to his commission, the ancient poet drives off the sin creatures, and explains to Alighieri that he’s going the wrong way. If he wants to reach Beatrice from where he is now, he must first descend into Hell, and then work his way back up again through Purgatory. Obviously that will be a long and dangerous journey, but Virgil will be acting under Heavenly orders and traveling under Divine protection; nothing in the lower regions will dare to threaten him. Seeing the sense in that, Dante agrees to follow Virgil’s lead, and the two pass through the Infernal gates together. We’ve already established, however, that we’ll be seeing only the first third of this adventure beyond the grave.

Dante’s ambition in writing The Divine Comedy was towering. Beyond the literary and linguistic objectives which I’ve already mentioned, he intended the epic as a plea for the comprehensive reform of Italian politics, both secular and religious. He sought an end to the incessant and wasteful warfare between the various Italian city-states; the renunciation of both tyranny and irrational, unprincipled partisanship within the individual republics and principalities; and most of all, a reorientation of church practice and policy away from the corrupting exercise of temporal power, and toward the spiritual health of Christendom. In a sense, then, his thinking really was the first tentative step in the direction of Italian nationalism, and despite his staunch support for the Papacy as an institution, he can be seen as a distant forerunner of the Reformation as well. None of that comes into focus, however, unless one takes The Divine Comedy as a whole. Read in isolation, The Inferno comes across instead as a cunningly disguised exercise in sheer bitchery, as Dante in his travels through Hell keeps bumping into recently deceased luminaries on the Italian political and clerical scenes, not a few of them players in the succession of dramas that led to Alighieri’s banishment from Florence in 1302. (Dante was a politician as well as a poet and a lovestruck weirdo, and his career in office offers an object lesson in the dangers of being a person of principle.) The film faithfully preserves that aspect of the epic, although it takes a firm grasp of late Medieval-early Renaissance history to extract much meaning from the poets’ encounters with the various named sinners. Most viewers will frequently find themselves asking, “Who was that guy in the burning crypt again? That was the punishment for the heretics, wasn’t it? And who is this tree talking about how he used to be human until he beat his head in against the dungeon walls after the Holy Roman Emperor had his eyes put out with red-hot tongs?”

So if there’s no real story to The Inferno, and most of the message is obscured by the decision not to film Purgatory or Paradise, and you need mastery of half a hundred obscure historical topics to follow what’s left, then what point is there in watching the movie beyond pigheaded antiquarian completism? That’s easy. You should watch The Inferno because it’s one of the earliest cinematic depictions of Hell, and because in that respect if no other, it is badass upon badass. It’s easy to forget how little of our modern pop-culture conception of Hell is in any way Biblical. The Old Testament talks a bit about a gloomy realm of spirits called Sheol (“the Grave”), and the New Testament mentions a lake of fire in which the unsaved are destroyed, body and soul, at the last judgment, but that’s it. Everything else is accretion from some other source— and The Inferno is unquestionably first and foremost among those sources. It’s where we get the nine circles, the city of Dis, the repurposing of figures from classical mythology (Charon, King Minos, Geryon, etc.) as Hell’s administrators. Dante’s notion of post-mortem tortures precisely and thematically calibrated to the nature and severity of the sins for which the damned are condemned is perhaps his most influential contribution, inspiring everyone from great artists like William Blake and Gustave Doré to the creators of Evangelical Halloween Hell houses. Blake and Doré in turn are the most conspicuous influences on Bertolini, Padovan, and de Liguro, who went to impressive lengths to translate the macabre and nightmarish imagery of their drawings and engravings to film. Every trick in the Méliès, Booth, and Chomon playbooks has been thrown at the subject here, along with unheard of exertions in the fields of monster makeup and fantastical set design. The directors made skillful use of location shooting, too, employing what looks like a partially drowned stone quarry as the basal layer of their Infernal vistas. It all looks very crude now, of course, but if you remind yourself that what you’re seeing lies nearer in time to Napoleon than to the present day, I think you’ll be able to find the frame of mind needed to appreciate it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact