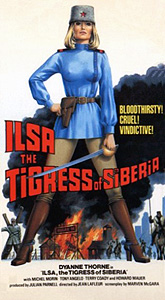

Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia/Tigress (1977) -***

Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia/Tigress (1977) -***

This last of the legitimate Ilsa movies doesn’t get much respect, even in exploitation circles. This is understandable, I suppose, if for no other reason than that Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia is the least Ilsa-ish of the series. Watching it, you never get anything like the feeling that you need to go shower immediately with industrial-strength disinfectant and a wire brush, the way you do with Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS, nor does it offer the boisterously excessive tackiness of Ilsa, Harem-Keeper of the Oil Sheiks. Instead, Tigress of Siberia represents an apparently conscious effort to take the series in a new direction (hell, a direction!) by beefing up an element to which both of the preceding movies gave short shrift— the plot. Alone in the series, this entry spends more time advancing the story than it does wallowing in filth, and thus it is, I think, that so many fans of its predecessors have found it disappointing to watch. And while I concede that it matches neither the shock value of the original nor the sleazy fun of the first sequel, I also like it a lot more now than I did when I first saw it a decade ago.

Dateline Siberia, 1953. Ilsa (Dyanne Thorne, returning for the last time)— who is never identified by name, incidentally— runs Gulag 14, one of the “Constructive Labor Camps” that were far and away the barbarous and inhumane Soviet system’s most barbarous and inhumane feature. Though technically a colonel in the KGB, it is obvious almost from the start that Ilsa considers herself a bit outside the system proper. She has almost as little respect for Lev, Gulag 14’s political commissar, as she does for the camp’s inmates, and her primary loyalty is to the band of Cossack shit-kickers who serve as the nucleus of the camp guard. While Lev spends his time attempting to “re-educate” dissenters like Andrei Chyakunin (Happy Birthday to Me’s Michel-Rene Labelle), Ilsa gives herself over more to the nights of superhuman drinking and group sex in her dacha-like cabin at the center of the camp. At these parties, Ilsa’s Cossack followers vie for the honor of sharing her bed by means of wrestling matches and drinking contests, with the last two men standing claiming the top prize while the remainder must content themselves with the two girls who are the closest thing to the usual pair of lesbian sidekicks that appear this time around. It’s an idyllic lifestyle (for Ilsa and the Cossacks, at least— the systematically brutalized prisoners would sing you a different tune), but it’s about to come to an end. 1953, you may recall, was the year that Joseph Stalin died, touching off a deadly power struggle between KGB head and heir apparent Lavrenty Beria and Nikita Khrushchev, which ultimately ended in Beria’s consignment to the same mammoth execution machine he had done so much to build. In the real world, that didn’t quite mean the end of the Gulag system (in fact, the Khrushchev years were worse for certain segments of the population), but it did mean an official disavowal of its worst excesses and a major shakeup of its administration. And the Soviet Union being what it was, we may be reasonably sure that it also involved a fair amount of the score-settling that now sets in at Gulag 14. One of Ilsa’s newest prisoners is a young man named Zirov, son of a troublesome general who would surely have followed him into the camps before much longer. But with Stalin gone, his enemies are now potentially valuable allies, and the nascent Khrushchev regime is currying favor with General Zirov by turning over to him command of the very camp where his boy is imprisoned. Ilsa knows very well what this means for her, and she sets her Cossacks to destroying the camp on the theory that the best chance for her to escape retribution from Zirov is to disappear into the wilderness with the Cossacks, leaving nothing behind her but a big pile of ashes and a barbed wire fence. And for the most part, her plan is a success. The trouble is, the one person not yet dead when she and those of her Cossacks as survived the final melee at Gulag 14 make their exit is Andrei Chyakunin, a man who had plenty of reason to hate Ilsa even before she burned an entire camp’s worth of prisoners alive.

25 years later, Chyakunin is the official Party babysitter for the Soviet national hockey team. This brings him to Montreal, and on the night before their return flight leaves, two of Chyakunin’s players talk him into accompanying them for an evening out on the town. As one of the men says, it’s been three months since any of the players has been with a woman, and it would be such a waste to return home without once bedding a North American whore. Chyakunin doesn’t directly participate, but he does escort his charges to the brothel and pay their way out of the team’s spending money. There’s something fishy about this whorehouse, though. (That’s not what I meant, goddamnit!) In both of the rooms where the Russian hockey players are being serviced, tucked away in a corner up next to the ceiling, is a little video camera; there’s one in the waiting room with Chyakunin, too. It is by means of these unobtrusive devices that the madam keeps watch over everything from a mansion on the outskirts of the city. And wouldn’t you know it, that madam is none other than Ilsa, still in business with ex-commissar Lev and Gregor (Jean-Guy Latour), the last of the Cossacks from her old camp. Evidently she’s been as successful in the criminal underworld as she was in the KGB, and has been steadily chipping away at the power of the various mafia families in Montreal ever since her arrival in Canada. When Ilsa spots Chyakunin on the video monitor, she jumps to the conclusion that he is trying to track her down for revenge, either personally or on behalf of General Zirov, and understandably takes steps to preempt any such plans. Communicating by radio with the brothel, Ilsa orders two of her men to apprehend Chyakunin, and bring him to the mansion for a stay in Lev's high-tech new torture chamber.

Ilsa’s involvement in Montreal’s prostitution industry comes as a total surprise to Chaykunin, but she’s right about one thing. He does work for General Zirov. Zirov is the Party official to whom he reports in his capacity as the handler for the hockey team, and when the team comes home to Russia without him, a lot of questions get asked. Zirov doesn’t buy the players’ idea that Chyakunin has defected. Rather, he correctly surmises that something happened to him at the whorehouse, and he immediately gets moving to figure out exactly what it was. Just a few days later, the general’s agents stake out the brothel, find the security cameras, and trace the cables controlling them back to Ilsa’s mansion, discovering thereby the identity of Chyakunin’s abductor. Then what I imagine must be the KGB gets to work, sending a commando team around to take the situation in hand.

It’s not exactly difficult to find fault with Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia, but I ask you— where the hell else are you going to see another non-Soviet movie made during the Brezhnev era in which the motherfucking KGB end up being the good guys?!?! That’s got to be worth something, right? I also think the filmmakers deserve some credit for trying to do something different with the series, turning it into a bit more than just an unusually sordid women’s prison franchise. The espionage angle that was at the back of Ilsa, Harem-Keeper of the Oil Sheiks comes to the fore in Tigress of Siberia, and while I agree that the balance tips a little too far in this direction, I enjoyed seeing a bit more action to break up the bondage and sadism aspects of the story. I also like the fact that Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia handles its sexploitation in a most unusual way. To me, the most remarkable thing about the Ilsa series (and the thing that would make it obvious that Ilsa the Wicked Warden isn’t really a part of it, even if I didn’t already know that movie was just Greta the Mad Butcher under a different title) is the completely uncompromising heterosexuality of Ilsa herself. In most sexploitation films, dominance in women is equated with lesbianism; not so with Ilsa. She might have lesbians working for her, but right from the beginning, Ilsa’s sexual interest has been in men exclusively. And right from the beginning, her sexuality has been one not of allure, but of power. Her dealings with men far more closely resemble typical male sexploitation-movie behavior than female, and in Tigress of Siberia, the converse of that is true as well. The numerous threesome scenes invariably involve two men; the majority of the bondage and torture scenes also involve male victims; most startlingly, Chyakunin at one point finds himself in the familiar feminine role of being betrayed by his own body when Ilsa attempts to seduce him against his will (although the scene in question doesn’t follow this premise through to its logical conclusion). All in all, there’s enough interesting stuff going on here to make me willing to overlook all the things Ilsa, the Tigress of Siberia doesn’t do, and to make me wish all the harder that the movie had been more successful at the grindhouse box offices. Had it made more money, we might have gotten to see one or two of the stillborn Ilsa movies that were to follow, and I, for one, think Ilsa vs. Idi Amin and Ilsa, Nanny to Royalty would have kicked ass.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact