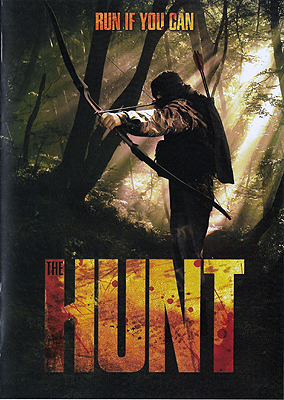

The Hunt (2010/2012) ***

The Hunt (2010/2012) ***

My longstanding fascination with this micro-genre being what it is, I donít often encounter a riff on The Most Dangerous Game that Iíve simply never heard of. What might be even rarer, though, is for me to encounter one with a twist on the formula thatís completely new to me. Iíve seen variations on the story where the ďislandĒ is an urban ghetto, or a tiny town in the country, or a war-torn Latin American jungle. Iíve seen versions where the hunted are hip teenagers, or special forces badasses, or debt-slave dancers at a down-market Southwestern titty bar. Iíve seen takes where ďCount ZaroffĒ is a renegade arms dealer, or a horny bisexual cannibal, or an invader from another planet. But never until Thomas Szczepanskiís The Hunt had I seen one in which the protagonist, instead of being the prey, unwittingly signs up to be one of the predators. The Hunt is a no-budget, direct-to-video indie release, so adjust your expectations accordingly. Nevertheless, it requires considerably less adjustment than most other films of its breed, and is far more rewarding than itís normally worth bothering to hope.

I donít know enough about France even to guess which city this is supposed to be, but itís decidedly on the skuzzy side, wherever it is. An unnamed Algerian youth (Zuriel de Pesoulan) is just going about his business when a bunch of burly guys in Mummenschanz masks kick down the door to his apartment, beat all the fight out of him with collapsible batons, and taze him unconscious. He awakens some unknowable time later to find himself sitting in a garage-like space with two men heís never seen before, both of whom presumably got there in much the same way. All three have been stripped of whatever clothing theyíd been wearing before, dressed in identical cheap suits, and outfitted with small hardshell carrying cases handcuffed to their wrists. The other two men also have their mouths stuffed with bloody rags, and the Algerian is just beginning to wonder about that when two of the Mummenschanz guys force open his mouth, and cut out his tongue. Soon thereafter, the menís captors chase them out of the building with handgun and rifle fire, but donít really seem to be trying to hit them. Thatís because the woods into which they flee are being patrolled by six heavily armed motherfuckers who have paid good money to kill the unfortunate captives themselves.

Meanwhile, Alex (Jellali Mouina), a ďreporterĒ for the sleaziest of sleazy tabloids, is in danger of losing his job. His editor (Marie Christine Jeanney) has not been at all satisfied with the quality of his work lately, which has descended into depths of gawking degeneracy that even her readers find objectionable. The editor wants Alex to knock off inventing salacious bullshit about women who fuck their dogs or whatever, and to return to the muckraking celebrity voyeurism that made his journalistic reputation in the first place. Sheís giving him a week to come up with something good (for exceptionally trashy values of ďgood,Ē naturally), or else heís out on his ass.

Thatís a tall order, and Alex is rightly dismayed by it. Fortunately, his buddy, Fred (Black Ariaís Frťdťric Sassine), is the proprietor of the skankiest jack shack in town, and one of his peepshow performers, a girl named Sarah (Sarah Lucide, of Last Caress), is much in demand among the sort of local luminaries who have lots of dirty laundry just daring people like Alex to air it out. Sarah is reluctant to get involved, but if Alex can give her an ironclad guarantee of anonymity, she does know something that might interest him. Thereís a big local businessmanó a crony of the mayorís no lessó who regularly pays Sarah to abuse him verbally and physically, in extremely perverse ways. Better yet, he likes to unburden himself of all his sins and misdeeds during these sessions, with results that Alex can well imagine. Best of all, he sometimes likes to have Sarah videotape their little get-togethers, and she knows where he keeps the tapes. Mind you, if Alex wants those (and he sure does), heíll have to get them his own damn self. This guy is dangerous, as Sarah stresses several times during the conversation, and nobody bats an eye when sex workers wind up dead in ditches.

Even so, Alex is not remotely prepared for the kind of trouble he calls down upon himself by breaking into Sarahís clientís apartment to hunt down the incriminating recordings. While heís ransacking the place, a telephone rings. Itís inside a heavy-duty duffle bag in the next room, and itís the kind of cheap cell phone that you buy when youíre expecting to have to destroy the thing later in order to cover your tracks. Alex answers on the theory that doing so might turn up another lead, and hits what he thinks is the jackpot. The voice on the other end of the line tells him that his registration has cleared, and instructs him to be at a certain telephone booth at a certain time. Naturally Alex keeps that appointment, and the voice on the other end of that line gives him directions to a manor house out in the country, along with a date and time of arrival. It also orders him to double his bet. Obviously some hugely illegal shit is going down here, the stuff of a story beyond Alexís editorís wildest dreams. Now it happened that, in addition to the burner phone, the duffle bag at the businessmanís flat contained hunting paraphernalia and a humongous pile of cash, all of which Alex helped himself to on the theory that it was going to be useful in this new journalistic sting operation of his. Now that heís heard the second phone call, Alex realizes that the stuff in the bag must be intended for whateverís about to happen at Swan Manoró and since the gear includes an identity-concealing hood mask, he figures he might as well go all the way, and infiltrate the mysterious criminal enterprise.

Alex is one of nine men who gather at the chateau on the appointed day, all bearing satchels much like the one he stole from the man whom he arrives impersonating. The master of Swan Manor (Michel Coste, who was in both Black Aria and Last Caress) announces that although heís pleased with the turnout, the rules of the game leave room for but six participants. All nine must ante up, of course (their stakes each go into their choice of three small hardshell carrying cases), but then the players of the game proper are chosen by lot. Alex makes the cut, although heíll soon have reason to wish he hadnít. After the odd men out vacate the premises, the other six are loaded into a van by more Mummenschanz guys, and dropped at a series of checkpoints, to which they are told to return at the gameís end. We, obviously, know whatís what, even before Alex sees a man in a familiar cheap suit fleeing through the woods, only to go down in a volley of broadhead arrows. It turns out, though, that thereís a nuance to this game that was not apparent from what we saw of the last time it was played. Since the nominal object is to collect the cash bets locked away in each targetís carrying case, and since each player is free to kill as many of the targets as luck and skill permit, itís only sporting that the players should also be allowed to kill each other in the event that their paths cross before the clock runs out. Principled abstention, in other words, isnít going to be a viable strategy for Alex to pursue.

I donít think itís necessary to share my nigh-limitless affection for Most Dangerous Game variants in order to appreciate The Hunt, although Iím sure it helps. What is necessary is a willingness to let the movie take its own sweet time working its way back around to the type of action weíre here to see after the Algerian gets whacked. Because of Alexís unique role, as compared to other interpretations of this premise, he needs to get drawn into the activities at Swan Manor one step at a time, and itís vital that he mistakenly feel himself in control of the situation at each stage of his descent. That takes a while, and whatís more, it means a detour through a very different sort of movie than The Hunt portrays itself to be. Itís almost as if All the Presidentís Men had concluded with Woodward and Bernstein outsmarting themselves by sneaking onto the guest list at G. Gordon Liddyís private hobo-hunting preserve. When I put it that way, though, doesnít it sound much more appealing than just, ďItís The Most Dangerous Game, only cheap and French?Ē

As is so often the case with modern direct-to-video productions, I had never previously heard of anyone involved in making The Hunt. In that respect, watching this movie was a bit like wandering into a divey little punk club on a random Wednesday night, and getting blown away by some nobody touring band from Morgantown, West Virginia. The presentation lacks polish, certain aspects of the script and direction could stand to be tightened up, and there are a few places where co-writer/director Thomas Szczepanski was obviously at the mercy of his budget. But the cast is rock-solid, Anna Naigeonís cinematography is some of the best Iíve seen in this stratum of cinema, and Szczepanskiís instincts as both a writer and a director are extremely sound on the whole. Also, as befits a French film, The Hunt makes the anti-aristocracy subtext inherent in nearly all Count Zaroff stories a bit closer to explicit than most, which perfectly suits my own outlook.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact