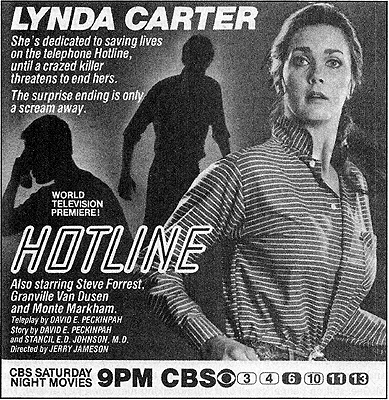

Hotline (1982) ***

Hotline (1982) ***

Nothing I’ve experienced has ever inspired in me such pure, sweaty-palmed terror as telling a woman that I’m attracted to her, and would like to pursue some manner of romantic or sexual relationship. Not getting beaten up by a skinhead; not losing control of my car on an interstate highway because some careless driver clipped my front fender while merging into my lane; not staring down a psycho who thought I was trying to come between him and his girlfriend (which, to be fair, I was)— nothing. No doubt this reflects some seriously fucked-up priorities on my amygdala’s part, but it’s true. The thing is, though, that I’m sure my own overtures have inspired their share of sweaty-palmed terror, too, especially when directed toward women who didn’t already know me well. After all, I know how I look. I’m tall. I’m burly. I spent much of my life dressing like an extra in a cheap post-apocalypse movie. And when I was younger and leaner, I had the face of someone whose crawlspace you’d be better off not digging around in. Also, even without any of that, I’d still be male. I don’t agree with Margaret Atwood on very much, but she was absolutely right about the asymmetrical worries besetting men and women in the realm of mating. Men really are afraid, in the worst-case scenario, that women will laugh at them, while women really are afraid, in the worst-case scenario, that men will kill them. That’s what the silly social media controversy over bears in the woods this past spring was ultimately about— and it also lies at the core of Hotline. Indeed, if any guys out there would like to try looking at the situation from the opposite point of view, this made-for-TV thriller would be a good place to start. Although it’s long on talk and short on scares, in that characteristic 80’s-telefilm way, Hotline dramatizes as effectively and engagingly as any movie I’ve seen the dilemma that confronts every sexually active straight woman in one way or another: what to do when your pool of potential mates is also your pool of potential predators, and there’s no foolproof way to distinguish one from the other until it’s already too late?

An aging but well-maintained Chevy Malibu is not the sort of vehicle you expect to see off-roading, so it’s immediately obvious that something is up when one of those ascends the grassy slope of a hill leading to a lonely stretch of sea cliffs in what appears to be the gray twilight just before dawn. The driver— whose face we pointedly don’t get to see— gets out, pops the trunk, and removes the bedsheet-enshrouded body of a dead woman. He drags the corpse to the edge of the cliff, then rolls it unceremoniously down into the surf and rocks below.

Fifteen hours or so later, atypically young widow and atypically old university art student Brianne O’Neill (Slayer’s Lynda Carter) reports for work at the Shadowbox, the honky tonk bar owned and operated by her longtime friend, Kyle Durham (Monte Markham, of Project X and Judgement Day). The crowd is rowdy tonight; the first thing Brianne hears from Judy the waitress (Joy Garrett) is a warning that “the fanny-grabbers are out in force.” Also, there’s a charming fellow at the end of the bar who keeps calling for Brianne’s attention by hollering, “Hey! Sweet-meat!” Kyle offers to throw the latter creep out, but the way he’s been tipping, Brianne is willing to put up with a little crudity. He’s still there come last call, when psychiatrist Justin Price (Granville Van Dusen, from The World of Darkness and The World Beyond) hurries into the Shadowbox, and asks to use the telephone. Evidently the doc has some low-grade professional emergency to handle, but more importantly for our purposes, his arrival at the bar puts him in place to witness Sweet Meat Lout’s threatening temper tantrum when Brianne makes it clear that the $20 in tips he’d given her over the course of the night have been insufficient to buy his way into her pants. Price is also on hand to observe the deft manner in which the bartender defuses the situation, without recourse to either Kyle’s authority or the baseball bat stashed under the Shadowbox bar for just such eventualities.

Deft might not be the same thing as successful, however. Brianne is too benumbed by her hectic night at work to notice this upon arriving at home, but she’s got a prowler sneaking around her house, peering in all the windows and waiting until she’s in the shower to jimmy the lock on the sliding door to the patio. This is a TV movie, though, so nothing further happens until she’s decently dressed— then there’s a knock at the front door. It’s Justin Price, of all people, asking if Brianne is okay. He says he found her place by following the randy drunk at the bar, who in turn was following her. And although Brianne initially takes that for the most far-fetched pickup line she’s ever heard in her life, she revises her position just a little when Price strolls in through the patio door, and asks if she knew it was open. Brianne calls the police, Justin agrees to hang around in order to give an official statement, and while the pair wait for some cops to show up, the psychiatrist does the last thing in the world that his host was expecting. He offers her a job! Price, it turns out, is the director of the Westside Hotline Crisis Management Program, a nonprofit phone bank organization for desperate people to call on those occasions when all it would take to stop them from doing something regrettably irrevocable is for someone to just fucking listen for a change. Between the way Brianne handled that drunk and the way she handled Justin when she thought he was just a higher class of sex-pest, the shrink figures she has exactly the natural gifts for diplomacy and rapid situation assessment that he needs in a telephone operator.

Now it happens that Brianne has been having trouble readjusting to the rhythms of student life after taking several years off to be a married, adult woman, and she’d been thinking of dropping back out of college anyway. Her house, meanwhile, isn’t really hers at all, but rather the result of an arrangement with a friend who had to leave town on business for an extended period. Price’s proposal is therefore more tempting than it might be for someone in more settled circumstances. Brianne drops by the Westside Hotline office the next day to see the operation for herself, and ends up discussing the nature of the work with Justin over lunch at a nearby restaurant. Their conversation sounds as much like a first date as it does like a job interview, and I don’t think either participant is certain that it isn’t one of those as well. Brianne also gets to show off a little when washed-up cowboy actor Tom Hunter (Steve Forrest, from Phantom of the Rue Morgue and The Living Idol) unexpectedly drops in, triggering an outburst of fanboy gushing from Price. She happens to know Hunter personally, because Kyle was his regular stunt double for many years before an on-set accident took Durham out of the movie business permanently. The two men remain inseparable friends even now. It’s worth noting, though, what Brianne leaves out of her explanation to Justin. Up until a month or so ago, she was actually dating Tom, until it turned out that he wasn’t really serious about making her his fifth ex-wife someday. In any case, Brianne decides as a result of her chat with the boss that the Westside Hotline is for her, and a call that Justin gives her to answer when they return to the office after lunch confirms his previous assessment of her aptitude for the job.

Some people’s problems are more disturbing to hash out over the phone than others’ however. Soon after joining the Westside Hotline staff, Brianne takes a call from a raspy-voiced man who wants to discuss his bad habit of hurting women. He doesn’t mean just, like, abandoning them, or cheating on them, or letting them down when they’re depending on him, either. No, when this guy says he hurts women, he means stuff like killing them, packing them into the trunk of his car, and dumping them over the nearest sea cliff. And he happens to mention this a few days before the discovery of the dead woman from the opening scene. What’s more, the killer— “the Barber,” he dubs himself, because he likes to cut off his victims’ hair before doing other, more permanent things to them— makes himself a veritable regular on the Westside Hotline phones over the coming weeks, always insisting upon speaking to Brianne. In each new call, he plies her with clues to one of his previous crimes, committed over a span of decades in places as diverse as London, Reno, and Idaho. Justin initially tries to reassure Brianne that this breed of phone freak is almost always nothing but talk, but each time she untangles one of the Barber’s riddles, it points her toward a genuine unsolved murder. And worse still, it eventually becomes apparent that the Barber is keeping tabs on Brianne’s movements, with such detailed accuracy that he almost has to be someone who knows her personally…

The key to Hotline’s effectiveness is the plausibility with which it casts suspicion on all of the men in Brianne’s life, while believably portraying her reluctance to believe that any of them could really be the Barber. At first glance, Tom Hunter looks like the prime suspect. He, after all, is the serially philandering ex-boyfriend, and he makes it clear at every opportunity that he hasn’t given up on winning Brianne back into bed with him. Furthermore, it comes out later that Tom has a long history of attachments to domineering, parasitic women, of just the sort that often leads men into misogyny. And perhaps most damningly, Hunter was in place to commit every one of the Barber murders, thanks to his filmmaking commitments throughout the 60’s and 70’s. But Kyle Durham was in all those places, too, and although he’s never made a move on Brianne in all the years they’ve known each other, there’s a faint but noticeable hint of “I wish that I had Jesse’s girl” in Kyle’s interactions with Tom whenever the latter’s continued interest in her comes up. As for Justin Price, his paternalistic, patronizing attitude toward the entire subject of Brianne’s least favorite repeat caller is not in itself much reason to suspect him, but his psychiatric background and his role as the organizer of the Westside Hotline undeniably do give him the conceptual and logistical wherewithal to frame a rival by inventing the character of the Barber and linking together case histories of several unsolved crimes. And when you get right down to it, don’t we really only have Justin’s word for it that the drunk guy from the Shadowbox followed Brianne home on the night they met? Also, Price has by far the best understanding of where Brianne goes and when, potentially accounting for the Barber’s most unnerving trick. Finally, I wouldn’t even rule out Lieutenant Ben Chandler (James Reynolds, from Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell), Brianne’s friend in the police department. After all, it’s only when Brianne involves the cops that the Barber escalates his telephone teasing to threaten her directly— and Chandler’s the one who ultimately tries to pin the whole thing on a crazy drifter who obviously isn’t the right man! I’m sure the actual reason for spreading the side-eye around like this was simply that it’s sound practice when making a mystery or thriller to keep the audience guessing. But in the context of this story specifically, it has the salutary side effect of emphasizing how little any of us really knows about the innermost minds of even those closest to us, and how high the stakes of that uncertainty are for women in particular.

It was a very canny move, too, to begin Brianne’s side of the film by showing her interactions on the job with an overbearing, entitled jerk, because doing so reveals something important about the minefields that women navigate in their dealings with men. Sweet Meat Lout does what he does because he’s attracted to Brianne, the repellant ugliness of his wooing technique notwithstanding. But he turns on her without a second’s hesitation once he understands that his attraction is not reciprocated. I defy you to find a woman anywhere who hasn’t had that experience in some form— and it’s a lucky few, I promise you, who haven’t had it in a form that conveyed at least the implicit possibility of physical violence, either. If a complete stranger can so sharply reverse his thwarted affections when the sum total of his investment is $20 in bar tips, what might a possessive ex-boyfriend be capable of? Or a longtime friend with a secret crush, curdling into secret envy? Or a new boyfriend who suddenly finds himself surrounded by previously unsuspected rivals? Meanwhile, for audiences in 1982, Hotline gave an extra twist of nastiness to Brianne’s travails just by casting Lynda Carter— fucking Wonder Woman!— in the part of the endangered and patronized protagonist. Carter herself seems acutely aware of that angle, too, deliberately shifting her performance into and out of phase with her earlier star-turn as a purpose-designed icon of female empowerment. Brianne may be sharp and plucky, but Carter makes sure we all understand that she’d be no match for any of the guys who might be the Barber in a stand-up fight. All she has to rely on is her wits, plus the frustratingly remote possibility that someone more formidable than her will take the danger confronting her seriously.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact