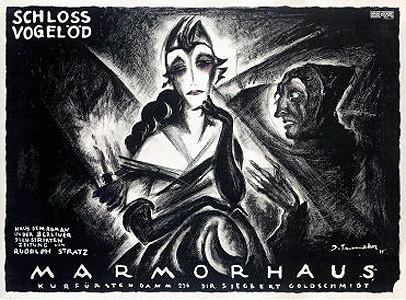

The Haunted Castle / Vogelod Castle / Schloss Vogeloed (1921) ½

The Haunted Castle / Vogelod Castle / Schloss Vogeloed (1921) ½

Let me begin by emphasizing the tremendous respect I have for F. W. Murnau. Nosferatu is an unqualified classic, Faust is high on the list of ancient flicks I’m forever on the hunt for, and I curse the loss of The Janus Head as vehemently as any Fellini-worshiping film snob. But The Haunted Castle/Schloss Vogeloed is another matter. A totally unmysterious murder mystery masquerading (in the English-speaking world at least) as a horror movie devoid of horrors, The Haunted Castle shows only that even the greats have their off-days. The only restless spirits on display here are those of the people foolhardy enough to attempt watching the film.

The Castle Vogeloed of the German title is the home of Lord Vogelschrey (Black Moon’s Arnold Korff) and his wife, Centa (Lulu Kyser-Korff, evidently Arnold’s real-life spouse). His Lordship has invited several of his aristocratic buddies to the castle for a few days of hunting in the forests of his vast estate, and when we join the party, they are still waiting for the last few stragglers to show up. The congenial atmosphere is disrupted, however, when Count Johann Oetsch (Lothar Mehnert) arrives uninvited. As one of the other guests— a retired county court judge (Hermann Vallentin of By Rocket to the Moon)— explains, Count Oetsch earned his place on the shit list through his part in a major scandal three years earlier. His brother, Peter, was murdered, and though he was never convicted, it was more or less universally believed that Oetsch was the one who fired the killing shot. His presence is doubly unwelcome at Castle Vogeloed on this occasion because two of the three guests who have not yet arrived are Peter’s widow (Olga Tschechova) and her new husband, the Baron von Safferstatt (Paul Bildt). Predictably, neither one is exactly thrilled to see Oetsch when they arrive. In fact, the baroness is so put out that she tells Centa von Vogelschrey that she and her husband will not be staying after all. But Centa has something up her sleeve that she thinks will change the baroness’s mind. The last of the late arrivals is another relative of her first husband’s, a monk from Rome named Father Faramund (Victor Bluetner). The baroness does indeed change her mind, but to judge by her reaction, the prospect of seeing Father Faramund again is not without its terrors for her either.

The old monk still hasn’t shown up come the next morning, and Vogelschrey’s guests are getting sick of waiting. Moreover, there’s been a break in the heavy rains that had characterized the day before, but the look of the sky suggests that it will not be a long one. If the men want to get any hunting done at all, they’d better get a move on. Oetsch, for his part, prefers to stay behind; as he tells one of the other guests— the credits identify him only as “The Frightened Gentleman,” but I propose we refer to him instead as Herr Huhnscheisse (Julius Falkenberg, from Dr. Mabuse the Gambler)— he goes hunting only in rain and storm. As it happens, only the count will be getting any hunting done today, it seems, for no sooner have Lord Vogelschrey and his guests reached the hunting preserve than the rain starts up again. Oetsch goes out, rifle in hand, as soon as all the others are back within the castle gates.

While the count is out, Father Faramund arrives at last. Baroness Safferstatt wants to see the monk immediately, and the old man is willing to oblige. There’s clearly something very important that the baroness wants to get off her chest, something which probably relates to the death of her first husband. Whatever it is, she begins by telling Father Faramund about the early days of her marriage to Peter Oetsch. They had been happy and carefree at first, but one day Peter went off on some sort of journey, and he returned a changed man. He had become introspective to the point of grimness, spending all of his time poring over ancient books and obsessed with the idea that true happiness could be found only in the total renunciation of worldly things. This transformation marked the end of the baroness’s happiness in marriage, partly because there’s nothing in the world more boring than hanging out with an ascetic, and partly (or so it is implied) because she herself counted as a “worldly thing” fit for renunciation. Eventually it got to the point where Peter’s dreary virtuousness drove his wife to seek satisfaction in its opposite, and the baroness began to crave a life filled with sin and iniquity. Finally… ah, but the lady is tired, and she cannot go on. Tomorrow His Reverence will hear the rest of the story.

The catch is that Father Faramund disappears during the night, quite without a trace and from within a locked and windowless room. Oetsch is the obvious suspect, and Vogelschrey’s guests, the judge in particular, waste no time in accusing him of a second murder. The idea that there’s a killer in the house, combined with a vivid nightmare (more on this later), is enough to drive Herr Huhnscheisse out of the castle altogether, while those who are made of sterner stuff become noticeably warier around Oetsch than they had been the day before. But while the accusations are flying, the count makes one of his own— it was not he who killed his brother, but rather the Baron von Safferstatt! Safferstatt practically faints when Oetsch calls him a murderer, and the judge, unfazed by the count’s words, lets it be known that he has notified the authorities both of Faramund’s disappearance and of Oetsch’s presence at the castle. Vogelschrey and his guests disperse throughout the house at that point, but the tense atmosphere between them remains.

So you can imagine everyone’s shock when Father Faramund comes back to Vogeloed shortly after nightfall. Without a word of explanation for his earlier vanishing act, he goes straight to Baroness Safferstatt to hear the rest of her story— her “confession,” as she calls it. She’s not kidding, either. This time, the baroness discloses that she, her first husband, and Baron von Safferstatt had been together a few days prior to Peter’s death. This was at the height of her “evil is fun” fixation, and she blurted out, apropos of nothing, that she’d love to witness the greatest evil of all, a murder. Evidently Safferstatt (who, one assumes, had figured out by this time just how unhappy her marriage to Peter had become) read that outburst as a thinly veiled wish for Peter’s murder specifically, and took it upon himself to grant that wish. It was the baroness’s guilt at her unwitting incitement of the crime that led her to marry Safferstatt shortly thereafter, and the two have been joined together by their damning secret ever since. The baroness can tell Faramund all this because he, as a clergyman, is bound by the confidence of the confessional; she can come clean to him without bringing the hand of law down upon herself or her husband. Or so it might have been but for one thing— Father Faramund is really Count Oetsch in disguise! (And it’s hard to think of a better disguise than being played by a different actor, while we’re on the subject…) “Faramund” leaves the baroness, and goes to see Safferstatt. When the baron asks why he has come, the wily count silently removes the glasses, wig, and false Karl Marx beard that had been the core of his disguise, and then tells him that he now knows the whole story. Safferstatt shoots himself the moment he is alone, Oetsch finds his way back into the good graces of Vogelschrey and his friends, and everyone, or so it would seem, lives happily ever after.

Considering how modernistic Murnau’s direction was in Nosferatu, it’s hard to believe that only a year went by between the release of The Haunted Castle and that of the better-known film. His handling of this movie is strikingly unimaginative, with utterly static camerawork (see if you can amuse yourself by counting the number of times you see the exact same frame setups of the castle’s front gate, drawing room, and main hall), completely lifeless lighting, and a distracting overreliance on the iris-out as a transitional device. (Although, to be fair, Nosferatu suffers from the latter affliction as well.) For me, the dominant impression was that any asshole who had been taught how to use a movie camera could have done every bit as good a job. It is in this context that the movie’s two dream sequences take on most of their interest. I’ve already hinted at one of these. On the night after Lord Vogelschrey finds Father Faramund’s room empty, Herr Huhnscheisse dreams that his window is blown open, and that he is dragged out through it by a furry, clawed hand. Then immediately thereafter, the camera cuts to another room, in which one of Vogelschrey’s servants is sleeping. This servant is a boy of perhaps twelve who works as an assistant to the lord’s chef, and whom we had earlier seen being punished by the chef for his insistence upon eating the cake icing that he had been charged with mixing up. The boy dreams that Father Faramund is feeding him the forbidden icing while he slaps the chef repeatedly across the face. (I myself couldn’t help but think of a symbolic interpretation for a dream in which a Catholic clergyman fills a young boy’s mouth with viscous, white fluid, but I’m probably just being disgusting…) Both of these dream sequences are brief, concern extremely minor characters, and add nothing at all to the plot. I’m tempted to speculate that Murnau found The Haunted Castle as boring to make as I found it to watch, and that these dreams and the useless characters who experience them were added by the director in an attempt to squeeze some small modicum of enjoyment out of this tedious film. At the very least, the dream sequences are the only moments in it that display even a hint of the surreal quality for which Murnau’s other work is justly hailed.

And with a screenplay like this, it’s easy to see why a man of Murnau’s talents would be bored. The Haunted Castle is all but plotless for its first half hour or so, and virtually all of what little happens over the movie’s course does so for the most artificial of reasons. The official story may be that Baroness Safferstatt is overcome with emotion, but when she interrupts her confession to Faramund/Oetsch in midstream, it seems far more likely that the real reason is that screenwriter Carl Mayer just needed some excuse to drag out the narrative by another 40 minutes. Furthermore, neither the baroness’s bizarre statement that she wants to see a murder nor her future husband’s drastic over-interpretation of that statement seem at all plausible given the slender motivations we are offered for them, while the reasons underlying Peter Oetsch’s conversion (if such it may be called) are given no explanation whatsoever. It has been said that a good author of fiction is invisible in the stories he or she writes. If so, then Mayer is about as bad a writer as they come; not a scene goes by in which he does not somehow draw attention to himself by the ludicrous contrivance of his plotting or his dialogue (though he was certainly not helped in the latter case by the translator of the intertitles, who obviously spoke little or no English). But the worst sin committed by The Haunted Castle— and the one for which Mayer and Murnau must share the blame more or less equally— is that it is a crushingly dull movie which seems as though it will never end despite a running time of less than 70 minutes. I’ll forgive stupid. I’ll forgive ridiculous. But I won’t forgive boring.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact