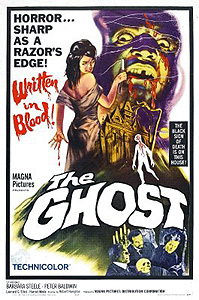

The Ghost / The Spectre / Lo Spettro / Lo Spettro de Dr. Hichcock (1963) ***

The Ghost / The Spectre / Lo Spettro / Lo Spettro de Dr. Hichcock (1963) ***

I’d been sitting on this movie for months. Knowing that it was the sequel to Riccardo Freda’s wonderfully sick The Horrible Dr. Hichcock/L 'Orrible Segreto del Dottor Hichock, I felt compelled to put off watching it until I managed to track down a copy of its predecessor. I needn’t have bothered waiting though; The Ghost is a sequel in name only, and has virtually no connection to the original film. In fact, this movie presents you with something close to the exact opposite of what they used to say at the beginning of the episode on "Dragnet"— the names are pretty much the only thing that hasn’t been changed! The story still revolves around a doctor named Hichcock, he’s still married to a woman named Margaret, his wife is still played by Barbara Steele (though I should point out that the Margaret-wife and the Barbara-wife were two different characters last time around), and Harriet Medin is still cast in the role of the conniving maid. Otherwise, the two stories have nothing to do with each other.

Now that I think about it, even one of the names has been changed a little bit. The Ghost’s Dr. Hichcock (Leonard Elliot) is called John rather than Bernard, and his field of expertise is slightly different. Instead of working with anesthetics, John Hichcock has devoted most of his energies of late to developing a cure for a certain form of paralysis. The form he himself is afflicted with, as a matter of fact. Hichcock is for all practical purposes retired now, as the disease that took away the feeling in his legs has come to sap his vitality too much for him to practice medicine any longer, and he has given himself over to the care of another doctor named Charles Livingstone (Peter Baldwin, of The Space Children and I Married a Monster from Outer Space). Hichcock chose Livingstone because he was the only physician he could find who was willing to risk treating him with his own technique, which is radical enough to scare away most doctors. The trepidation of the medical establishment is perfectly understandable; Hichcock contends that two chemicals which are both powerfully toxic on their own will, when combined, not only counteract each other’s lethal effects but undo the progress of his disease as well. Of course, one must make absolutely certain to get the dosage just right, or whichever chemical it is that is administered in too great a quantity will kill the patient.

Hichcock doesn’t realize this, but that’s just what his wife, Margaret (Steele, from The She-Beast and The Crimson Cult), is hoping will happen. Margaret is sick to death of being married to a morbid old cripple. Indeed, she and Dr. Livingstone have become lovers over the months that Charles has been dwelling under the Hichcock roof, and Margaret never lets slip an opportunity to harangue the young doctor in favor of mixing her husband’s drugs incorrectly one of these days. Charles, for his part, wants his inconvenient patient out of the way just as badly as Margaret does, but he can’t quite bring himself to kill Hichcock outright. Rather, Livingstone prefers to wait until his host dies of his own illness, on which the former doesn’t seriously believe the two-toxin treatment will have any useful effect. But Margaret wins out in the end, and Livingstone is persuaded to botch the following evening’s injection. The results are predictably deadly.

Dr. Hichcock was a wealthy man, and this point has not been lost on either conspirator. But Charles and Margaret are in for a string of surprises when the notary comes by to read the doctor’s will. Margaret gets the house and its associated land, of course, but only one third of her late husband’s liquid assets, and even then her inheritance is conditional on her continued employment of Hichcock’s old maid, Catherine (Harriet Medin, who may as well be playing Martha from the last movie again). The bulk of his fortune is dedicated to the local vicar (Umberto Raho, from The Wild, Wild Planet and The Bird with the Crystal Plumage), whom Hichcock unaccountably never recognized for the smarmy little weasel he so obviously is. All the money is locked in the safe in Hichcock’s old study, but when the notary goes to open it, he discovers that the key has gone missing from its usual resting place in the doctor’s desk. This development leaves everyone’s hands tied for the moment; evidently Scottish law in 1910 requires a special court order for a dead man’s safe to be forced open.

And if they can find the key, it also gives Margaret and her lover a chance to keep their hands on a bigger share of Hichcock’s money. The will didn't specify how much was supposed to be in the safe, you know. If the key should turn up, the scheming couple could pocket a certain proportion of it before the notary came back to see to its division according to the will. They spend most of a day tearing the house apart before Catherine remembers an important detail that just might solve the problem. She saw her master put the key to the safe in his vest pocket a couple of days before he died, and in all probability, that’s where it can still be found. The catch is that Catherine is talking about the vest in which Hichcock was buried. Charles and Margaret are determined to get the money before the vicar, though, so after sunset, the two of them sneak out to the doctor’s crypt, pry open his coffin, and go fishing around in his pockets. The key proves to be right where Catherine said it was. You know what isn’t where it’s supposed to be, though? All of Hichcock’s money. The safe is empty of anything but a few old papers when Charles opens it up later.

But this is supposed to be a movie about a ghost, isn’t it? Quite right, and as the days following Hichcock’s demise wear on, it becomes increasingly clear that the doctor’s spirit is haunting his killers. Hichcock’s wheelchair begins roaming the mansion’s corridors all by itself. Catherine starts talking in her sleep with the dead doctor’s voice. Eventually, Margaret can scarcely get through a night without being menaced by visible manifestations of Hichcock himself. And while all that’s going on, hints begin surfacing that Charles has secretly been pursuing an agenda of his own. For example, it occurs to Margaret that she wasn’t actually in the room at the precise moment when Dr. Livingstone opened the safe— there was more than enough time before he showed her its empty confines for him to stash its contents in his medical bag, which he then took with him to work the night shift at the hospital. Not only that, when Margaret follows the directions of her husband’s ghost (speaking, as usual, through the slumbering Catherine) in order to find the true hiding place of the Hichock fortune, all she turns up is an empty coffer. Finally, tensions between the two conspirators reach the point where Livingstone has had enough, and the doctor packs his bags to move out of the house, abandoning Margaret, the money, and indeed everything he committed his crime to get in the first place. But Margaret interrupts his packing, and she notices a bunch of expensive jewelry in one of his bags. Paying no heed to Livingstone’s protests that the jewels were planted there by someone else, Margaret slashes her erstwhile lover half to death with a straight razor, drags his unconscious body to her husband’s crypt, and sets him on fire. There’s one important point of which Margaret is unaware, though— writer/director Freda has clearly seen Diabolique...

It may disregard The Horrible Dr. Hichcock almost entirely, but anyone who enjoys Mario Bava’s moody, languorous gothics from the same era will find much to like about The Ghost. While it’s true that Freda lacks Bava’s visual flair, he has a similarly firm command of atmosphere in his own way, and is just as good at wringing a claustrophobic air of sinister secrecy out of a period setting. Even the absence of The Horrible Dr. Hichock’s attention-grabbing necrophilia angle is partially made up for by this movie’s much more effective use of Barbara Steele. The role of the gothic heroine is so tightly circumscribed that an actress with Steele’s vibrancy will almost inevitably be wasted on it. Far better to cast her as a character with a pronounced bad streak, and give her more to do than faint, scream, and be rescued. What doesn’t get compensated for in the transition between The Horrible Dr. Hichcock and The Ghost is the wonderful open-endedness that arose from the former movie’s refusal to explain itself. All questions are answered and all loose ends tied up by The Ghost’s conclusion, preventing Freda from repeating his trick of creating a movie that becomes more and more disturbing with each extra minute you spend thinking about it. Still, as a straight-ahead gothic, The Ghost succeeds more than it fails, although I do have to wonder why Freda felt compelled to present it as a sequel to a totally different and significantly better movie when it was perfectly capable of standing on its own two feet.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact