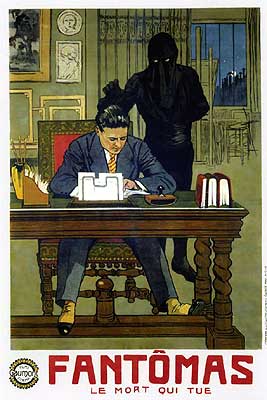

The Murderous Corpse / Fantomas III: The Murderous Corpse / The Dead Man Who Killed / Fantomas: Le Mort qui Tue / Le Mort qui Tue (1913) ***Ĺ

The Murderous Corpse / Fantomas III: The Murderous Corpse / The Dead Man Who Killed / Fantomas: Le Mort qui Tue / Le Mort qui Tue (1913) ***Ĺ

So as I was saying, while Juve Against Fantomas is the most serial-like of Louis Feuilladeís Fantomas movies, The Murderous Corpse is the most like a modern feature film. Thatís a little strange, because the in media res ending of the previous installment forces this one to begin in midstream as well. But Feuillade handles the transition so that the post-cliffhanger cleanup works more as a prologue to the new story than as its inception proper. From there, Feuillade takes us into what is clearly the domain of the feature sequel, catching us up with characters whom we havenít seen in a long time (from their frame of reference, anyway), all of whose lives have been changed significantly by the events of the preceding films. And with a full 90 minutes in which to spread out and stretch its legs, The Murderous Corpse comes as close to modern notions of pacing as was realistically possible in its day, when those notions were just starting to be sorted out. Most significantly, The Murderous Corpse weaves its various plot threads throughout its whole length, dispensing with the episodic structure that Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine and Juve Against Fantomas employed to better or worse effect before it.

When we last saw the diabolical criminal genius Fantomas (a returning Rene Navarre), he was blowing up the mansion of his sometime mistress and accomplice, Lady Beltham (Renee Carl again), putting one decisively over on the cops who had tried to run him to ground there. Only one survivor was pulled from the wreckage, La Capitale reporter Jerome Fandor (still Georges Melchior)ó although itís worth noting that the body of Inspector Juve was never found. In this genre, thatís as good as a promise to bring the missing man back from the dead, so weíll all smile smugly to ourselves when the scene shifts to the crooked pawn shop run by Mother Toulouche, and weíre told that she only just recently engaged the services of her halfwit stock boy, Cranajour. (Is that Edmond Breon under all that obvious makeup? Of course it is.) There are more immediately familiar faces hanging around Mother Touloucheís store, too. For instance, hereís Josephine (Yvette Andreyor), the avaricious gal from Juve Against Fantomas who may or may not have realized that her tough-guy boyfriend, Loupart, wasnít just any criminal, but Fantomas himself. And thereís Nibet (Naudier), the corrupt prison guard who smuggled the crime lord off of death row in Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine. So if Cranajour really is Juve, heís got excellent reason to get close to Mother Toulouche. Itís a hell of a fencing business the old lady runs, too. In the cellar below her legit pawn shop is what amounts to a showroom for stolen valuables, conveniently accessible from the sewers to the River Seine. Those in the know can buy whatever Toulouche is selling without so much as being seen entering the premises.

Thatís all a little beside the point just now, though. A more immediate concern is the studio apartment on the Rue Norvins in Montmartre where painter and ceramist Jacques Dollon (The Green Ghostís Andre Lugnet) awaits a visit from his lover, the Baroness de Vibraye. What he gets instead is a visit from three men in costumes that would later be copied by the villains of a hundred Krimis. Their leaderó I think itís safe to assume that heís Fantomasó chloroforms Dollon while his accomplices leave behind a little present: the dead body of the baroness. When Dollonís maid understandably calls the police the following morning, they arrest the artist under suspicion of murder. Dollon doesnít last long in jail, however. One of his guards is our old buddy, Nibet, who makes sure to strangle the prisoner in his holding cell before heís so much as stood trial.

Fandor is recovered from his injuries by this point, and back to work at the newspaper. He rushes to the jail at once when a tip comes his way about Dollonís murder, arriving in time to meet the dead manís sister, Elisabeth (Fabienne Fabreges). Fandor is also on hand to witness the even more startling discovery that Dollonís body has gone missing. Elisabeth finds it in her heart to hope that the empty cell means Jacques has escaped, but everyone who saw him that morning is quite certain he truly was dead. The mystery deepens further when Elisabeth returns to the apartment she shared with her brother, and discovers an enigmatic list of correlated names and dates. Sheís no detective, of course, but since the first two entries are Baroness de Vibraye and Jacques Dollon, both dated with the night of the womanís murder, it seems likely that this is a vital clue.

The third name on Elisabethís list is one weíve heard before. Itís Sonia Danidoff (Jane Faber), the Russian princess whom we saw Fantomas rob way back at the beginning of the first film. And it just so happens that sheís now engaged to marry the fourth person on the list, a wealthy sugar planter called Thomery (Luitz-Morat). Their engagement party occurs on the 12th of April, the very date specified in Soniaís entry, and sure enough, she falls victim that night to a crime bearing the unmistakable signature of Fantomas. Once again, the princess loses a priceless pearl necklace, and once again, the thief has secreted himself in her quarters to perform the theft. This time, though, the culprit would be known to his victim had he not knocked her out with chloroform before she saw his faceó and whatís more, heís on the list himself. So does that mean Fantomas is impersonating Nanteuil the investment banker to draw suspicion away from himself, or does it mean that there was never any such person at all, and that Nanteuil is but another of the criminalís multifarious alter egos? Thereís a disturbing extra wrinkle to this latest crime, too. Nanteuil/Fantomas left a fingerprint on Soniaís neck when he attacked her, and the police anthropometry lab matches it to the supposedly deceased Jacques Dollon.

Three weeks later, Nanteuil is playing hanky panky with Thomeryís stock prices, apparently with an eye toward turning their ups and downs to his own advantage. Unexpectedly, he receives a visit from Lady Beltham; itís an ambiguous scene, but I gather that she must have learned somehow about his activities, and thought she recognized her old boyfriendís style. Their reconciliation, if you can call it that, leads to Lady Beltham being sent on a mission to bait Thomery into a trap using pearls from the stolen necklace. Thomeryís death scene will bear Dollonís fingerprints, too, when it is looked over by the police.

Obviously that list Elisabeth found is looking more incriminating than everó obvious to Elisabeth and Fantomas alike. Having learned of Fandorís investigation when she met the reporter that day at the jail, she gets in touch with him to arrange a handover of the document. What she doesnít realize is that the handyman at the Bourrat boarding house where sheís staying (because of course a young lady canít live aloneó who knows what kind of trouble sheíd get up to with no one around to stand guard over her vagina?) is really a member of the Fantomas gang. When he canít find the list in her room, he tries to prevent her writing to Fandor about it. When he canít stop her from summoning the reporter, he lets Fantomas into the house, and helps him rig a bogus suicide by lamp gas for the girl before she has a chance to deliver the list itself. And when Fandor arrives in the nick of time to rescue Elisabeth, the criminals return with their leader disguised as a police inspector bearing a phony search warrant. It happens, however, that Fandor is there again when the gang tosses Elisabethís room, and they inadvertently smuggle him into their own headquarters in a trash hamper when they cart their ďevidenceĒ away. Thatís both a tremendous danger and a tremendous opportunity for the reporter. Fortunatelyó as we long ago figured outó an old ally has been keeping tabs on Fandor all this time, and knows when to come forward with a more active sort of assistance.

So have you solved the mystery of the murderous corpseó of how Dollonís fingerprints keep winding up all over the scenes of Fantomasís crimes, long after the unfortunate artist is killed? Iím going to give it away, because the mystery per se is of only minor importance, whereas the solution to it goes further than anything else I can name toward explaining why this is the best and most engaging of the original Fantomas movies. Other tales of diabolical geniuses might try to wow us with gloves of synthetic material (remember that plastics were an infant technology this early in the 20th century, their limitations little understood and their possibilities a topic worthy of speculative fiction), molded from the dead manís fingertipsó indeed, exactly that concept figured in The Hands of Orlac eleven years lateró but Fantomas is a more practical sort of arch-criminal. Why bother copying a victimís fingerprints when you can just use the originals? Thatís rightó when Fantomas and his gang stole Dollonís body from the prison, it was so that he could flay the dead manís hands to make the perfect pair of crime-committing gloves! If it wasnít obvious before why I was harping on a character from a series of fanciful crime movies as an example of Franceís vital early contribution to the development of horror cinema, that ought to spell it out. By embracing such a macabre premise, Feuillade finally succeeds in making Fantomas the figure of terror that heís always been stipulated to be. Before, we had to take Feuilladeís word for it, but not anymore.

It also helps a lot that The Murderous Corpse splits up Juve and Fandor for most of its length. For one thing, doing so creates a satisfying progression across the three movies thus far. Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine was almost entirely Juveís show with regard to the hunt for Fantomas; Fandor was around, but he was basically a bystander. In Juve Against Fantomas, the detective and the reporter were a team, supporting each otherís efforts and watching each otherís backs, although Juve was clearly the senior partner. And now, with Juve presumed dead, Fandor is forced to come into his own, taking up the fight against Fantomas without official aid. Meanwhile, Juveís nominal absence paradoxically elevates him to a stature he never previously had, for when his behind-the-scenes activities are formally revealed, it proves that the inspector can play Fantomasís game as well as Fantomas himself. Everyone loves an underdog, but that dynamic gets boring after a while. Especially when the bad guy is someone like Fantomas, sooner or later you want to see how he fares against an evenly matched opponent.

The single best thing about The Murderous Corpse, however, is simply how well all its elements and components hang together. This picture has, if anything, even more subplots than its predecessors (three or four major ones, depending on whether you count the Dollon siblings together or separately), each with its own largely separate cast and settings, and yet theyíre all mutually reinforcing rather than getting in each otherís ways. And because they all run concurrently instead of in sequence, thereís no sense, as there was in Juve Against Fantomas, of starting over at the beginning halfway through the film. (Fantomas: In the Shadow of the Guillotine had a built-in excuse for a restart thanks to the villainís early incarceration.) It always feels weird praising an antique movie like this for something as basic as narrative cohesion, but it really was kind of a big deal in 1913 to make a 90-minute film in which everything feels well balanced and fully integrated. When youíre used to telling a story in fifteen or thirty minutes, telling oneó and only oneó in an hour and a half is hard. The learning curve from one-reeler to feature is steep even today, and Feuillade and his contemporaries were the first to try scaling it. If youíre curious about the silent Fantomas, but donít want to embroil yourself in a five-part series sight unseen, then The Murderous Corpse is the place to start. Just know going in that youíll be missing some nuances that youíd catch automatically if you began at the beginning.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact